10 Ways To Buy Happiness

The Art of Spending Well

Catch-up service:

Fake Debates and Late Converts

Suicide as a Bargaining Tactic

Notes on the Greatest Night In Pop

Rationalist Cults of Silicon Valley

How Humans Got Language

The Diderot Effect

Just over a decade ago, an idea took hold among the Ted Talk classes: that money buys happiness only up to a point. The ‘happiness plateau’ was first proposed in 2010, when Daniel Kahneman (psychologist) and Angus Deaton (economist) published a study which found that day-to-day happiness increases with annual income, but levels off after about $75,000 (adjust for inflation as necessary).

It is a plausible idea: that money matters only insofar as it enables us to acquire a measure of financial security, together with what you might call the necessary luxuries of modern life - a decent place to live, a car, holidays. After this point, we clamber up Maslow’s Pyramid towards immaterial satisfactions, and spending power ceases to be significant.

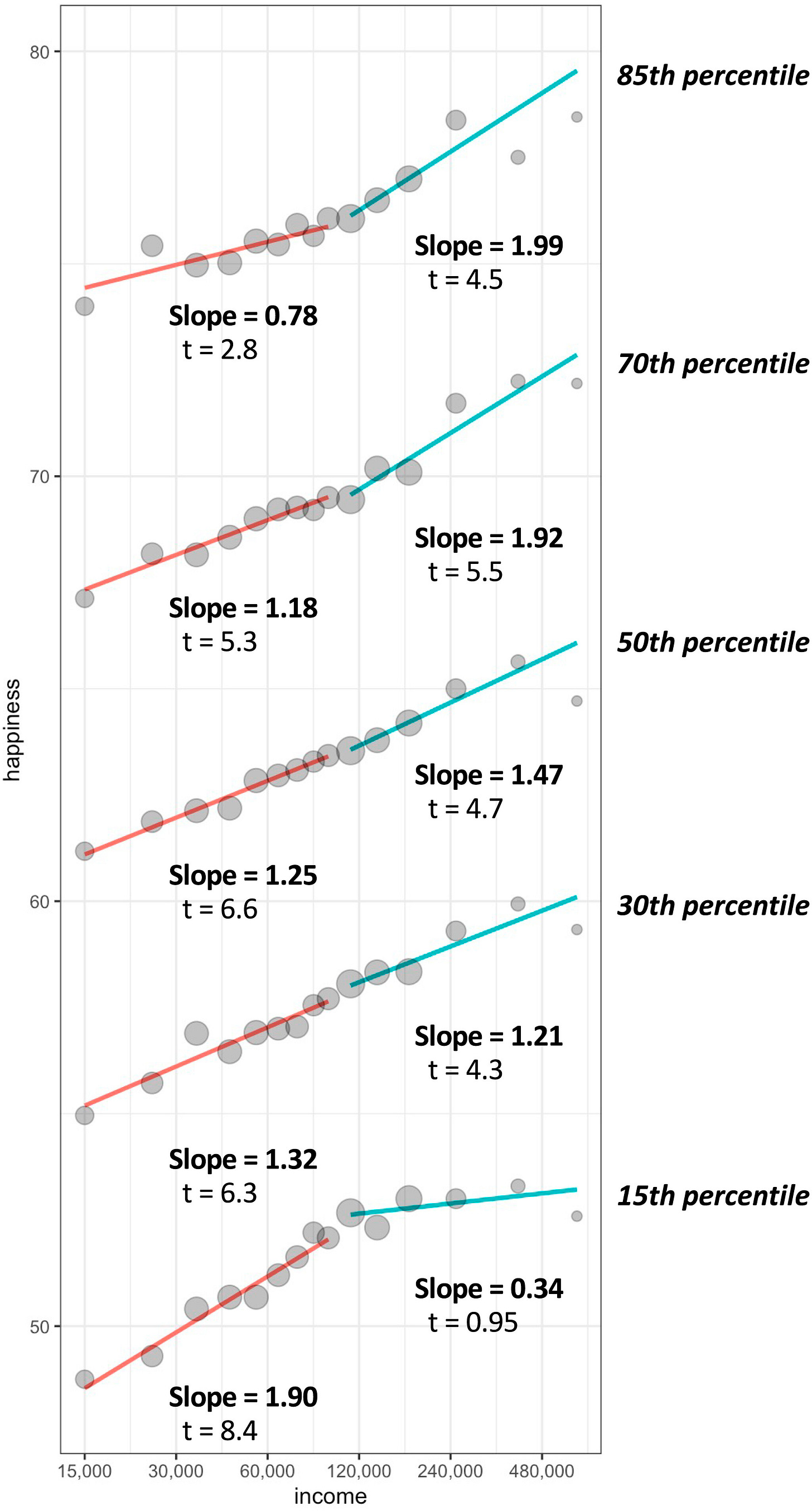

Plausible, but false, for the happiness plateau has been debunked. A more comprehensive study by Matthew Killingsworth at Wharton, published in 2021, found that well-being rises steadily with income well beyond $80,000, with an equally steep slope above as below. Kahneman himself accepted this finding and collaborated with Killingsworth on a new study. This one found that happiness steadily increases with income a long way after $100,000, and that for people who tend to be happy anyway, it actually accelerates. The plateau or flattening effect that Kahneman and Deaton identified is real but applies only to the least happy 20% of the population:

In other words, the more money you have, the more happiness you can buy. But you will get more happiness for your buck if you have an instinct for it in the first place.

We have read about or know people with heaps of money who are nevertheless miserable, or just well-off people whom we can’t help but think aren’t making the most of the money they have. No doubt much of this comes down to genes and upbringing and other forms of luck. But it’s also to do with the choices people make, the strategies they consciously pursue. Spending well - spending in the pursuit of happiness - is a vital component of well-being.

It’s hard to write on this topic without sounding like Marie Antoinette, especially with so many dark things happening in the world. But it is worth trying to think about it intelligently - yes, even in this economy. Consumerism, or spending money on somewhat unnecessary things, is an activity that takes up a lot of time, effort, and, let’s face it, money. It involves satisfaction and reward, hope and disappointment. It is part of the way we form our identities and shape our life stories. Even after financial security has been achieved, it is a determinant of happiness. It matters.

Yet I haven’t seen much good, first-principles advice on how to think about spending from a philosophical or psychological point of view, perhaps because of the Antoinette factor. I think we need better guidance. There are people better qualified than me to do this (I’m thinking of you, India Knight), but here are my 10 rules for spending happy.

Know your Diderot Unity. A Diderot Unity is a harmonious collection of possessions or lifestyle. An individual consumer’s gestalt. I’d say the difference between top and bottom quintiles in the chart above is really between people who know what they want to do with money and people who don’t. To be more specific, people who have a clear mental model of the good life, or their good life, and people who just buy things. Let me explain.

As money becomes a less stringent constraint on what you buy, you face an increasing number of choices both within categories (‘Should I buy the premium olive oil?’) and across them (‘Should I take up golf?’1). That’s liberating and exciting but it can lead to anomie if you buy too many things that don’t reflect who you are in some way. When your desires are allowed to ramble on without form or punctuation, you become a bore to yourself. You also become subject to whatever the market tells you are your desires.

Better to impose your own constraint, in the form of a mental model of the life you aspire to - a personal aesthetic or felt philosophy which isn’t a product of fads, fashions and marketing campaigns but which is unique to you. This model becomes your filter, your discriminator at the margin, your razor. Does this potential purchase fit my model or not? What does the model suggest that I save for next? What am I building towards with this purchase?

The model will always be a work in progress, you will never achieve it, but that’s what keeps it interesting. Some people have their Diderot Unity deeply internalised, so that they never really need to reflect on it (that is, they have that rare and precious talent we call ‘taste’). Others have to think it through more effortfully.

It’s worth doing. In a recent post on similar themes, Sherry Ning cited René Girard: “All desire is a desire for being”. Ning adds, “Every desire points to a way of life, a kind of person we long to become.” If this is so, then we ought to decide what we want our desires to add up to; on what, or who, we want to be.Distrust impulse. One of my razors for life is “stick to the plan”. In spending terms, that means ignoring most impulses to buy. Now, I don’t want to be a total killjoy here; impulse buys can certainly provide delight and satisfaction. But a high proportion of them end up being counted as mistakes, and if you accumulate too many of these mistakes you can end up feeling empty and foolish.

When it comes to bigger items in particular, the act of purchase should be the culmination of a thought process - one which has been whirring away at the back of your mind, if not always consciously pursued. The key is that the desire for a specific item should emerge from inside you, rather than being imposed in the moment.

One problem is that the impulse to buy can feel authentic even when you’re being tricked into it by a conspiracy of mental state and market. ‘I’m hungry’ (literally or figuratively) comes together with a product telling you, ‘This thing you’d never even consider normally is going to be the best thing you ever had’ and whoops, you’ve spent a fortune on something that leaves you feeling dumb and cheated. Time is the best protection against this kind of mistake. If you didn’t want it a year ago you probably don’t need it now; if it can’t wait until next week, perhaps you don’t really want it today.Consume stories. While some have ethical reasons to avoid cheap products like fast fashion, I avoid them because the stories behind them are either non-existent or fake and dull. Products made by interesting companies or craftspeople are worth paying more for in part because of what we know about them. The satisfactions of these intangible attributes are just as real and legitimate as material ones. All those smug pieces about how expensive wines are a waste of money because drinkers can’t distinguish them in blind tests completely miss the point. A wine lover knows full well they are buying the story - the vineyard, the terroir, the maker - as well as the liquid in the glass. They wouldn’t have it any other way.

Read on for the next seven rules. Plus thoughts the latest American violence; Mandelson’s exit; more on Gladwell and trans sport; is human intelligence hitting a wall; a stunning photo, and a sublime piece of music.