A Deep Dive Into 'I Feel Fine'

A Two-Minute Microcosm of Twentieth Century Pop

Catch-up service:

Pitfalls of AI Journalism

Bodies Behaving Badly

Centrism’s Anger Problem

All Hail the Putter-Togetherers

The Stamina Gap

Has Paul McCartney Read My Book?

I realise that not all Ruffian subscribers are Beatles fans but even if you’re not I hope you’ll find this interesting, because it’s about how musical ideas travel and collide in time and space.

Oh and a quick piece of celebratory news: the UK paperback of John & Paul hit number one in the Sunday Times bestseller list last weekend! Thanks to everyone who bought a copy.

The Beatles released I Feel Fine as a single in November 1964. It became their sixth number one of that year. I Feel Fine is like a magic box. Take the lid off and inside you can glimpse the whole history of twentieth century music.

It was recorded in October in the middle of a schedule that was crazy even by Beatles standards. In the previous nine months they had made a movie, A Hard Day’s Night, and an album of the same name. They had toured America, Britain, Europe, and Australia. Now they had to record a second album in time for the Christmas market.

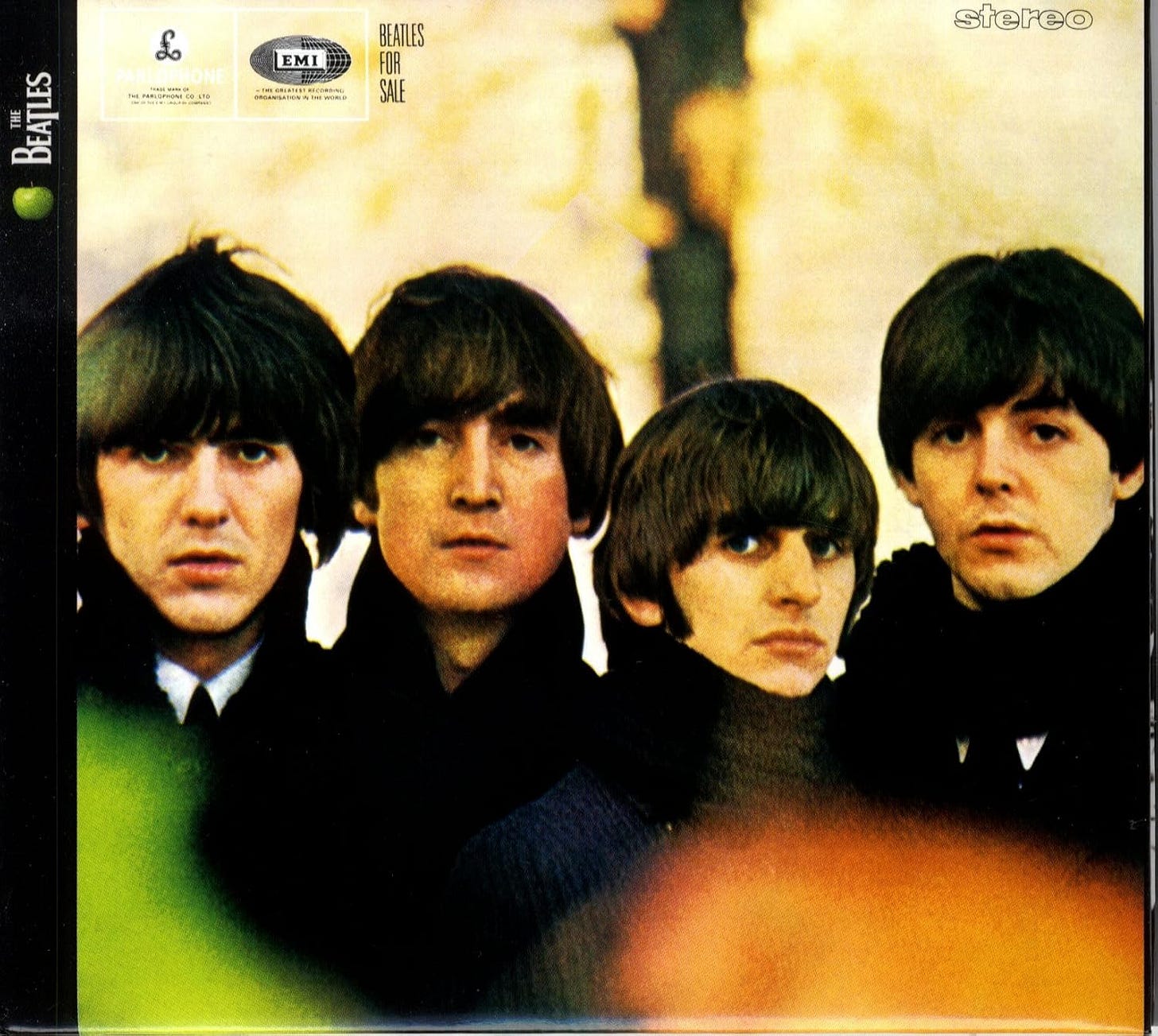

Beatles For Sale included several rock n’roll covers they knew by heart and could knock out at speed. Its Lennon-McCartney originals had a downbeat or reflective flavour (No Reply, I’m a Loser, I Don’t Want To Spoil The Party, I’ll Follow The Sun). The Beatles were getting sick of being treated like cash cows and they were tired. Their mood is evident in the weary defiance with which they stare out at us from the album’s cover, and in the mordant joke of its title.

But with the exhaustion came a certain frazzled, giddy liberation. You can hear it in the wildness of the rock n’roll covers like Kansas City/Hey Hey Hey, which threaten to tip into chaos. And you can hear it, in a different way, in I Feel Fine, the title of which sounds almost ironic in context. (I Feel Fine wasn’t on the album, it was released only as a single, though it’s from the same sessions). The song is so effortlessly enjoyable that we tend to think of it as a throwaway. But it was a major step forward for the group in several ways.

I Feel Fine was originated by Lennon. It the first Beatles track to be built around a guitar riff (a repeated phrase or figure played on lead guitar). It was a trick they would use in a few singles, including Day Tripper and Ticket To Ride, also originated by Lennon. John wanted The Beatles to keep up with and exceed the efforts of groups like The Who and The Kinks who had followed in their wake but had a rockier, more riff-based sound. The Kinks’ You Really Got Me had just been a big hit. He started playing around with a riff from an R&B song the Beatles used to play at the Cavern which John in particular loved: Watch Your Step by Bobby Parker (1961).

You can hear how similar the riff is, although Lennon and the Beatles subtly transform it. We’ll come back to that but first, let’s marvel at how influential Parker’s riff was. Not only did it inspire I Feel Fine (and Day Tripper) but a host of subsequent rock songs, from Led Zeppelin, The Yardbirds, the Allman Brothers, and more. Watch Your Step was also covered by many artists, including Adam Faith, Manfred Mann, The Spencer Davis Group, and Carlos Santana. It was an enormously generative song.

Watch Your Step was itself heavily influenced by a couple of prior songs. Parker said he came up with the song after playing around with the riff from Manteca, a 1947 hit by the jazz trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie. Parker said, “I started playing [‘Manteca’] on my guitar and decided to make a blues out of it.”

The jazz critic Gary Giddins called Manteca “one of the most important records ever made in the United States.” Why? Because it successfully combined Latin rhythms with jazz, inaugurating one of the most fruitful cross-pollinations of in twentieth century music.

The transatlantic slave trade distributed West African musical traditions across the Americas, where they evolved differently depending on local conditions. In the U.S. South, they fused with Anglo-Celtic folk and hymn traditions to produce blues, gospel, and eventually R&B. In Cuba and elsewhere in the Caribbean and in South America they fused with Spanish and Portuguese forms to produce samba, calypso, mento, and so on.

After the war, New York, in particular Harlem, became a point of convergence. Black jazz musicians and Cuban/Puerto Rican musicians were playing together, listening to each other, living in the same neighbourhoods. It was in Harlem that Dizzy Gillespie came across the Cuban drummer Chano Pozo, a legend in his home country. Gillespie had already attempted to introduce Afro-Cuban rhythms to big band jazz, but it was only after getting together with Pozo that he struck gold.

Pozo came to him with an idea for a piece based on a repeating, Latin-inflected riff made up of interlocking bass and horn vamps. With Pozo playing the drums it sounded irresistibly exciting. Gillespie added a beguilingly melodic be-bop bridge with opulent harmonies, turning Pozo’s vamp into a complete piece of music. Manteca had its premiere at Carnegie Hall. It was an immediate success, and a big hit. It still sounds like dynamite.1

After Manteca, Latin and Afro-Cuban rhythms increasingly found their way into jazz. By the late 1950s and early 1960s, they could be found in pop, too, in hits like Under The Boardwalk and Stand By Me. The young Beatles played Latin-inflected songs like Bésame Mucho and Till There Was You.

Ray Charles brought Latin beats into R&B. Along with Manteca, Bobby Parker cited What’d I Say by Charles, from 1959, as a big influence on Watch Your Step. What’d I Say combines Latin rhythm with twelve-bar blues. Charles and his band were drawing on rhythmic ideas that had been circulating through American popular music for over a decade by that point. Parker then took the feel and energy of What’d I Say and combined it with his Manteca-like riff to make Watch Your Step.

The Beatles adored What’d I Say. It was a staple of their sets in Hamburg and Liverpool, though it was only after Ringo joined that they were felt they were playing it properly. In early 1962, Ringo subbed in for Pete Best in Hamburg. The group opened their set with What’d I Say. McCartney later recalled this as the moment he and the other Beatles realised what they had been missing.

Which brings us back to I Feel Fine. John had his variation on Parker’s riff and an idea of how the song would go. He enlisted the group to help him work out the rest of it. The lyrics are simple and have the feel of being written at speed. It’s unclear who out of he and Paul contributed what to the song, and at this stage they were working so closely that the question is moot, although both agreed it was mainly John’s song.

Structurally speaking I Feel Fine is closer to Manteca than Watch Your Step or What’d I Say. Those last two tracks have the same structure: they repeat the main idea over a 12-bar blues chord progression. They are repetitive, albeit in a deliberate, concentrated way. They want to lock you in to the groove until you lose your mind. What’d I Say is a very long track, over five minutes. On stage in Hamburg, the Beatles liked to make it longer still.

I Feel Fine has a very different feel. It’s two minutes long and it isn’t a twelve-bar blues. Rather being heavy or intense, it’s deliberately light. It’s pop. This different sensibility is manifest in what Lennon does with Parker’s riff. Instead of going around on the same three notes over one chord at a time, he creates a more open, more playful figure which spins us through different chords before settling down. Rather than locking us into a groove, it opens us up. The Beatles were already capable of writing more sophisticated lyrics. But the simplistic, frictionless words of I Feel Fine are perfect for a song which aspires to flight.

Like Manteca, I Feel Fine has two parts: the main section, dominated by the riff, and a melodically expansive bridge which offers a contrast in feel (“I’m so glad…”). We could just as well call it the chorus. Whatever it is, it works. I’ve heard the song a thousand times and this section still feels likes the sun coming out. It is the perfect complement to the bluesier, sexier verse, like someone beautiful and cool taking off their Ray-Bans and just grinning. The vocals are a major contributor to this magical effect. Paul and George join John for one of those glorious technicolour three-part Beatle harmonies.

The bridge is made up of two simple musical phrases: “I’m so glad” and “She’s my little girl” which are then repeated with varied words (“She’s so glad/She’s telling all the world”) - though not quite. A straight repeat of that melody would have worked fine and in the hands of lesser songwriters, that’s what we would have got. But the Beatles introduce a melodic variation on that second phrase - “She’s telling all the world” - a delicate little turn that skips up before descending with the elegance of Fred Astaire dancing down a staircase. It’s a phrase which gestures to jazz and Broadway, while returning us seamlessly to the bluesy, rocking verse.

When Lennon brought the song to the studio, he told Ringo, “I’ve written this song, it’s lousy.” You can see why John would have dismissed it. It was just a riff, a simple two-part structure, and lyrics about nothing very much sung to a narrow melody that is barely a melody at all. But the difference between the mediocre and the sublime can be surprisingly slim, a matter of execution. It was only once they went to work on it as a group that the song really came to life. It didn’t happen immediately. Judging by the outtakes, I Feel Fine evolved rapidly from the version they began with. In the small number of hours they had, they changed the song’s rhythm, its key, its bassline, and its vocal arrangement.

The crucial advance came when Ringo landed on the What’d I Say beat. His ability to nail that rhythm owed much to his love of swing and jazz. Before he introduces it to I Feel Fine, John isn’t swinging his vocal line in the way he does in the final version. I Feel Fine sounds, well, fine, but not nearly as good as the song we know. Once the song was infused with Latin jazz, with Ringo making it sound so effortless and spacious, and John and George playing that killer riff in unison, the Beatles knew that they had their next single.

Millions of teenagers in Latin American countries now heard the music of home refracted back to them by the world’s biggest pop group. We can get an idea of what that meant by hearing the way Gloria Estefan talks about the Beatles:

I Feel Fine opens with a brief snatch of feedback before the famous riff kicks in. That metallic whine may not sound like much now, but it was momentous: the first time electric feedback had been deliberately used on a record. By 1964, guitarists like Jeff Beck, Pete Townshend and Jimi Hendrix were using feedback on stage and would soon make flamboyant use of it in the studio. But at the time of I Feel Fine, the idea that you’d put feedback on a record was outrageous. Recording engineers considered it an ugly waste product to be avoided at all costs. The Beatles had to persuade horrified EMI technicians to break their own rules.

That shows us that by 1964 the Beatles had already assumed control of their creative output in a way that few if any pop acts had done before. They were also beginning to treat the studio as an instrument in itself, rather than as a place to translate live performances on to vinyl records. The inclusion of a couple of seconds of feedback at the start of this feather-light pop song leads to Tomorrow Never Knows and Strawberry Fields Forever, two years later. It was the harbinger of a revolution in twentieth century music which followed a pattern identified by Brian Eno:

“Whatever you now find weird, ugly, uncomfortable and nasty about a new medium will surely become its signature…It’s the sound of failure: so much modern art is the sound of things going out of control, of a medium pushing to its limits and breaking apart. The distorted guitar sound is the sound of something too loud for the medium supposed to carry it. The blues singer with the cracked voice is the sound of an emotional cry too powerful for the throat that releases it.”

It’s worth going a bit deeper on how the I Feel Fine feedback came about. The version most often told is that John propped his switched-on guitar against McCartney’s bass amp and got intrigued by the resulting feedback noise. He and Paul then decided to put it on the record. That’s a fair summary, but it misses out some illuminating details.

Feedback is what happens when amplified sound loops back on itself. When the strings of a switched-on electric guitar vibrate, the guitar converts those vibrations into electrical signals, which the amplifier plays through its speaker. Feedback happens when the guitar is close enough to the amp that the sound waves from the speaker cause the guitar strings to vibrate again, which causes the guitar’s pick up to send an electromagnetic signal back to the amp, and so on: the cycle repeats and intensifies, until the amp overloads and you get that familiar screech.

That’s not how the feedback we hear on I Feel Fine was produced, however. This sound is a little more controlled than normal feedback noise. It has a fairly stable tone, a definite pitch. It’s essentially an A, a note which is in G Major, the key of the song, and thus leads nicely into the riff that starts the song proper. It’s part noise, part music. A very Beatles way to break the frame.

What seems to have happened is this: Lennon’s semi-acoustic guitar (a Gibson Jumbo) was very close to, or leaning against, McCartney’s bass amp. John liked the sound this produced and invited Paul to experiment with him, and they ended up producing this more sophisticated form of feedback.

This is how it works. Paul hits an open A string on his bass. The sound waves from Paul’s amp physically vibrate the strings of John’s Gibson. These sympathetic vibrations are strongest at the harmonic frequencies of Paul’s note. John then holds his vibrating guitar up to his own amp, which amplifies those vibrations, further excites the strings, and creates this relatively controlled, musical feedback. They made different versions of it for different takes.2

In other words, the brief but revolutionary noise at the start of I Feel Fine is not quite the straightforward studio accident it is often presented as, but the result of purposeful experimentation - and the sympathetic vibrations between John and Paul.

Nobody executed quite like the Beatles. All those years of playing and creating and living together enabled them to spin a little masterpiece out of thin air. Of course, that air was actually thick with virtual collaborators, some of whom they knew and loved, like Parker and Charles; some they would have counted as competitors, like The Kinks, and others they didn’t know much if anything about, including a bullfrog-cheeked jazz trumpeter and his Cuban sideman. I like to imagine the latter two in particular being present at the recording of I Feel Fine, invisible except for their cigar smoke.

The best available mix of I Feel Fine is the one from the 2023 Red album, as remixed by Giles Martin. It’s the one where you can hear Ringo’s drumming in all its glory.

Acknowledgements: it was an episode of the brilliant Beatles podcast, Note By Note, which revitalised my interest in the song, and this piece owes a debt to their analysis. I also drew on insights from A History of Rock Music In 500 Songs (the song is covered in the episode on Ticket To Ride) and from Gary Giddins’ essay on Manteca in his collection, Faces In The Crowd.

Chano Pozo is an unsung hero of American music. As a member of Gillespie’s band, he electrified audiences with dramatic solos on congas, which he played stripped the waist, his body oiled and gleaming. A year after Manteca was recorded, Pozo got into a fight over a woman. An accomplished brawler, he got the better of his opponent. The next day, he was standing at a jukebox in a Harlem bar as it blasted out Manteca, when the man entered and shot him dead.

In technical terms, this kind of feedback is called the Larsen effect, named after Danish scientist Søren Larsen. It uses acoustic sympathetic vibration as the trigger rather than electromagnetic pickup feedback, which locks onto specific harmonic frequencies, thus producing something more musical than random screeching.

Ringo is so underrated. Without him, you don't have the Beatles. Other drummers had more flash. Keith Moon may have literally blown stuff up. John Bonham may have raged on the thin line between control and mania. But Ringo made magic.

One of the Fabs' songs which stopped me in my tracks on first hearing it way back in 1982. Really good examination of a key Beatles track