A Studio 54 Immigration Policy (or Why Liberals Should Learn To Love Bouncers)

The Progressive Case For Border Control

Catch-up service:

10 Ways To Buy Happiness

Fake Debates and Late Converts

Suicide as a Bargaining Tactic

Notes on the Greatest Night In Pop

Rationalist Cults of Silicon Valley

How Humans Got Language

I am excited to be talking John & Paul with Samira Ahmed at Wimbledon BookFest on October 25. As well as being one of our finest broadcasters, Samira is a Beatles superfan and highly perceptive about the group, so this is bound to be a great conversation. Book your tickets here.

Today’s post is free to read, with a juicy Rattle Bag of links and notes after the jump, for paid subscribers only.

When Britain’s new home secretary, Shabhana Mahmood, was appointed to the role, she addressed the staff at her new department. Mahmood was previously Justice Secretary and tasked with the job of fixing a prisons crisis. She told the Home Office that she used to think that was the toughest job in government. “I can tell you, very precisely, the moment that I stopped thinking that was the day I became home secretary.”

Of course, that’s not strictly true: the toughest job in government is Keir Starmer’s speechwriter. But it’s close. The most urgent task for Mahmood is to secure Britain’s borders against illegal immigration, which will be hard. If successive governments have failed to stop people arriving in containers or small boats, it’s not simply down to lack of will or competence. It’s because a web of logistical and legal complications make it a wicked problem. This is distinct from but entangled with the question of how to manage legal immigration. Voters think there’s too much of that too. Immigration currently tops the list of voters’ concerns and by a long way.

Others better qualified than me can tell you what Mahmood’s policy options are, and the likelihood of her making headway on either of these challenges. But simply from a political point of view, I was heartened by something else she said at that meeting, while speaking of her determination to get a grip on illegal immigration:

“Some people have written this off as simply a political imperative. But that is to misunderstand who I am and what I believe. Sovereign countries have secure borders. That statement is an article of faith for me. We can only be a tolerant, open, generous country when we are able to determine who can enter and who must leave. And I know that a country that can control its own borders is a far safer country for someone who looks like me.”

Reading this felt like drinking a cool glass of water on a hot day. First of all, it’s lucidly expressed. That shouldn’t be remarkable, but the bar for political communication is low. So much of what our politicians say is mangled by non-sequiturs, vagueness, and jargon. Here, each plainly-worded proposition builds on the one before. An actual argument is constructed.

Secondly, it provides philosophical ballast for her governing priorities. I don’t mean anything high-minded by that; I just mean that she is clear in her own mind about why securing the border is important, at the level of bedrock principle. In those few sentences, she connects the policy goal to her worldview, and her life-story. She isn’t just aiming to crack down on illegal immigration because voters demand it, or the media is on her case, but because she really believes in it.

If you lack the conviction that comes with clarity of thought, then its absence soon becomes painfully apparent. Mahmood’s boss, the Prime Minister, presents himself as a pragmatic problem-solver, but because he doesn’t have a deep sense of which problems are most important, or how he wants to solve them, he relies on others - pollsters, advisers, celebrities, news editors - to tell him. Since they all say different things, he conveys the impression of an empty suit flailing in the wind.

To be fair to Starmer, all of his recent predecessors at No.10 suffered from a similar handicap. No Prime Minister since 2016 has had a firm idea, or strong intuition, for what to do with power, and consequently all found themselves overrun by events. Without purpose, power dissipates. (Truss was a different case: she had the ‘why’, but went about the ‘how’ in such a destructively haphazard manner that she self-immolated).

The third and most important reason I like this passage is that it does something which Labour politicians - and their peers elsewhere, like the Democrats - have historically been terrible at: it makes a principled progressive case for a robust immigration policy. It’s not a new argument, but surprisingly few on the left have been willing or able to make it so clearly. Leftists and liberals might pay lip service to controlling the borders, but they rarely seem to believe in it as anything but an unfortunate and slightly grubby necessity.

As this government struggles to react to Reform, you often hear voices on the left urging it to “make the positive case for immigration”. By that they generally mean, “Remind voters of the many ways in which immigrants enrich our country, economically and culturally, while denouncing bigotry”. It’s not that this case isn’t right - I believe it - but it’s an old tune that voters find it easy to ignore. More fundamentally, it doesn’t address why fair-minded, tolerant voters might worry about immigration in the first place. It just tells them they’re wrong to.

By contrast, Mahmood signals that such concerns are legitimate, and not in that distant, officious “I understand the concerns of voters” way, but personally and directly. As a Muslim and daughter of Pakistani immigrants, she has a particular kind of authority here. She convincingly connects the liberal ideal of a diverse and fair society, of which she is a living embodiment, to the conventionally conservative imperative of border control. She makes a synthesis (which isn’t the same as a compromise) out of two seemingly opposed political positions.

A cohesive society of any kind depends on selectivity: on keeping people out as well as welcoming them in. Clubs, universities, political parties, actual parties, all operate on this principle. A book club that admits people who never read becomes useless to everyone. The left has always struggled to accept this axiom, but you can’t have fair female sporting competition if men are included. You can’t have a tolerant society if you include too many of the intolerant.

Clear entrance criteria, strictly enforced, create space inside the club for freedom, equality, and fellow feeling. The welfare state, another priority for the left, depends on a national culture which joins, and overrides where necessary, all local cultures. Voters will accept the principles of universality and redistribution so long as they feel some connection to, and therefore some responsibility for, their fellow citizens. A democracy cannot last for long as a purely legal construct.

Earlier this year, Starmer said “we risk becoming an island of strangers”, a phrase he later disowned because of its accidental echo of Enoch Powell. He was right to separate himself from Powell but wrong to disown the phrase. A recent poll found 59% of voters agreeing with it. That’s a strikingly high number, particularly since respondents were told it came from Starmer, who is extremely unpopular. It ought to ring alarm bells for anyone who cares about the future of the country and its social institutions.

I recently watched a documentary about Studio 54, the legendary New York nightclub. This temple of diversity and joyful self-expression was also of course, a fiercely elitist institution which carefully policed new entrants for cultural fit. Andy Warhol is said to have described it as “a dictatorship on the door, but a democracy on the dance floor”. There are worse models for a country.

Indeed you could say that’s the model adopted by that eminently liberal democracy, Denmark, which has tighter immigration control than most European countries. It also takes tough action to dismantle “parallel societies”, breaking up social housing projects when more than half the tenants are immigrants, relocating people into mixed communities. The Danes do all this precisely to promote diversity, toleration and cohesion.

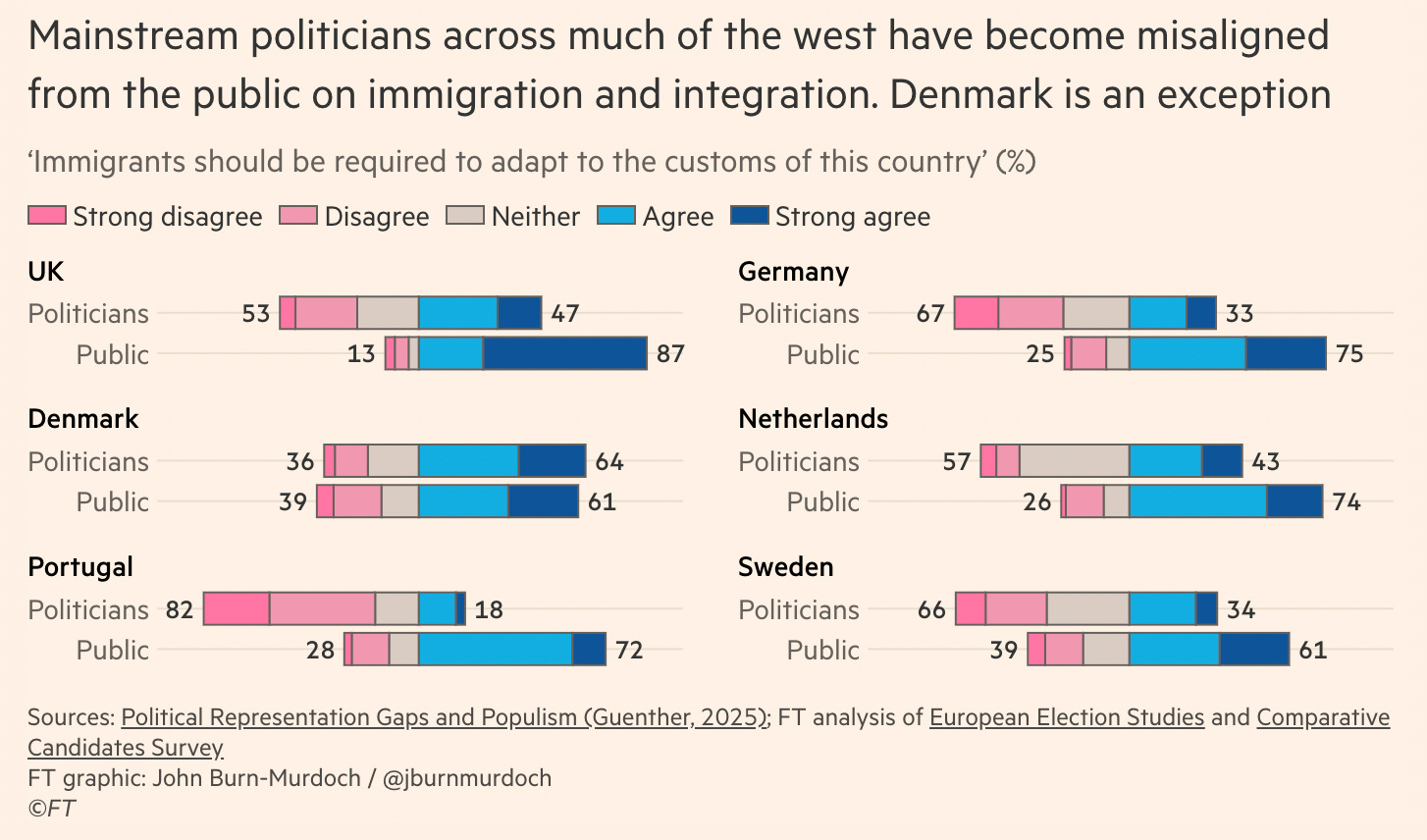

It works. The chart below is from John Burn-Murdoch’s typically excellent column this week. It extends the findings of a major new study which finds that mainstream politicians in Western countries are generally more liberal on immigration and crime than their voters. The major exception to this rule, as you can see below, is Denmark. Having toughened up its immigration policy in recent years, it has left little space for populist insurgencies; Denmark is also exceptional among European countries in not having a rising and vigorous far-right movement.

British voters have the most positive attitude to immigration and immigrants in the developed world. Anecdotally, foreigners who have lived and worked internationally frequently report that Britain is more welcoming than other European countries. Following the Brexit referendum, British voters became increasingly liberal about immigration, presumably because they assumed that politicians were now getting a grip on it - which didn’t necessarily mean reducing it, but controlling it. Concerns fell to their lowest level for over twenty years.

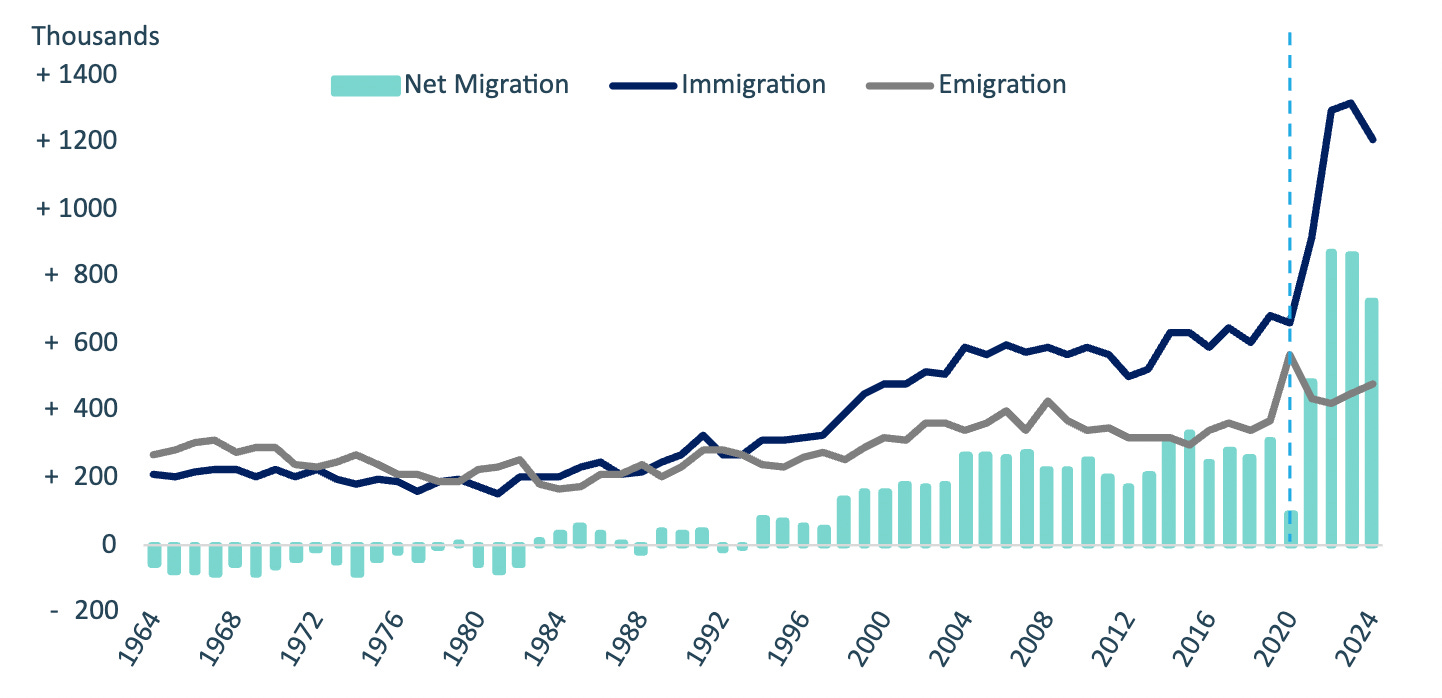

But at some point they began to feel that those in power were, to speak British, taking the piss. The recent rise in salience of immigration isn’t because Nigel Farage is a mass hypnotist. It’s a response to the size and velocity of this post-pandemic (and post-Brexit) surge in immigration:

Viewed at historical scale, that increase, which came largely from non-European countries, is breathtaking, and it was made worse by the way neither main party did much to acknowledge or explain it. Current anger about small boats and hotels may well be disproportionate and ginned up by TikTok racists. Concerns over legal immigration have become mixed up with those around illegal immigration and other, darker fears and frustrations. But I don’t think any nation on earth would have responded to a shift of this magnitude and speed with perfect equanimity.

Political scientists like to place voters somewhere on a scale between authoritarian and liberal. But a lot of voters are authoritarian liberals, happy to live alongside very different kinds of people as long as they feel confident they’re there for the right reasons. I suspect Mahmood’s position puts her closer to the median voter than either most Labour MPs or Nigel Farage. Most people are not inherently anti-immigration or anti-immigrant. They just want to know there’s someone on the door.

This piece is free to read so please share and recommend if you enjoyed it.

After the jump: good news on teenage depression; why humans start off with lizard hands; why LLMs lie; a football star with very good taste in classical music; the fastest period of social change in history; three excellent podcast eps on Israel, China, and art; why the climate movement needs a rethink; thoughts on the classic novel I just finished; and a fun education in the musical styles of different composers. If you’re not yet a paid subscriber, join us! But wear a sequinned jumpsuit or you’re not getting in.