All Hail the Putter-Togetherers

What Scissors Can Tell Us About The Future of Work

Catch-up service:

The Stamina Gap

Has Paul McCartney Read My Book?

Best of The Ruffian 2025

How The Mad Men Lost The Plot Again

How To Do Politics When Nobody Knows Anything

When The Mind Outlasts the Brain

I’ll be talking John & Paul with Helen Lewis at Union Chapel, London, on February 12. Book your tickets! The paperback edition of John & Paul is now available for pre-order.

Before we get going, here’s a little ad for a journalistic enterprise I’m proud to support:

Have you heard of Britain’s OnlyFans Triangle? Curious about Kent’s Hells Angels? Or Ireland’s underground ayahuasca retreats? Dispatch is a new online magazine committed to longform storytelling. Imagine Vice crossed with Vanity Fair. In keeping with the theme of this week’s Ruffian, Dispatch is a work of craft. In a world of hot takes and AI slop, it sends curious reporters out into the world to discover what the hell’s going on in the weird and wonderful corners of the culture. Readers get two deeply reported pieces a week and a lively Sunday newsletter in their in-box. Dispatch is endlessly surprising and never dull. Most articles are free to read. Sign up here.

“A pair of scissors, no less than a cathedral or a symphony, is evidence of what we hold good and therefore lovely, and owes its being to love.” Eric Gill.

I’ve been reading Craftland by James Fox, an exploration of Britain’s last great craftspeople: blacksmiths, wheelwrights, bell-founders, cutlers and coopers (one of the book’s joys is the music of occupational names, more of which later). Most of the things we buy and use are mass-produced, mostly overseas, but not all. In British workshops and homes and warehouses there are still humans engaged in intimate and purposeful negotiation with physical materials.

There is, inevitably, an elegiac tone to the book. Many of these arts and crafts are remnants of once great industries which supported thriving communities, and some are dwindling to nothing, as the last inheritors of an institution or tradition give up or die. But there is energy here too: the defiant, quixotic energy that comes from people who choose to swim against the tide. Anyone producing chef’s knives or watches in Britain today is doing so because they believe in what they make - because they are obsessed by it.

Craftland offers insights into the future as well as the past. It is a close-up study of human work which arrives in a moment when we’re all trying to understand what that means - what kinds of work are specifically and indelibly human. It also serves as a reminder that everyday objects are more multi-faceted and intricate than we think, as is the work involved in making them.

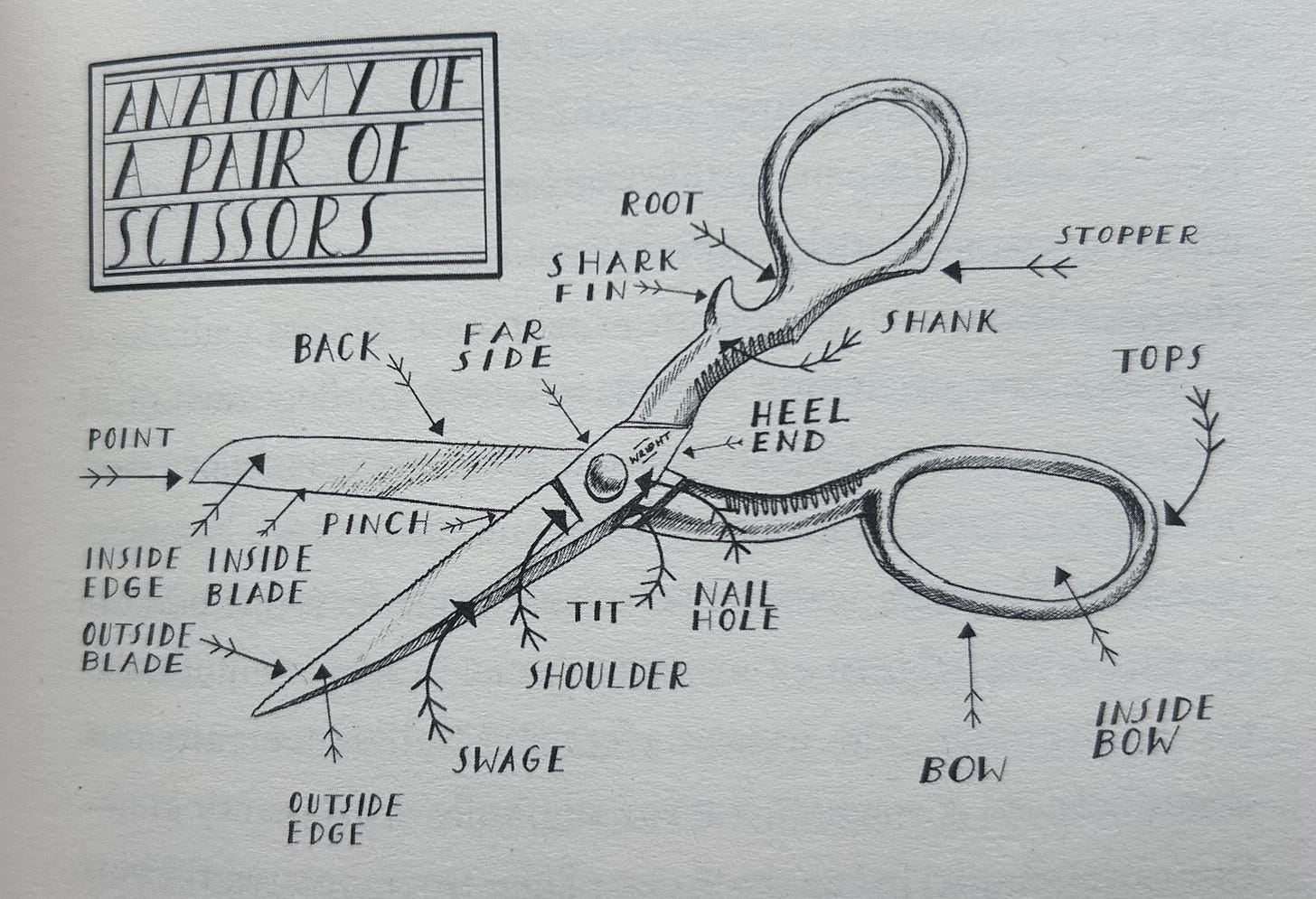

Take scissors. A good pair of scissors is a wondrously complex little machine. As Fox puts it, it involves “a dance of two perfectly calibrated parts that touch but don’t touch, meet but don’t meet, their movements aligned to within a hair’s breadth.”

In Sheffield, Fox goes to visit the workshop of a scissors-making company called Ernest Wright. At one point in the nineteenth century, Sheffield had at least sixty scissors manufacturers employing thousands of skilled ‘scissormen’. Ernest Wright is one of two still in existence. Founded in 1902, it thrived right up until the late twentieth century; in the 1970s it was one of the world's leading scissors brands. By the turn of the twenty-first century the business was in inexorable and harrowing decline. In 2018, Nick Wright, a member of the fifth generation of the family to run the business, committed suicide, and Ernest Wright Ltd went into administration.

That might have been that, as with so many of Britain’s industrial businesses, except in this case two Dutch entrepreneurs called Paul Jacobs and Jan Bart Fanoy came to the rescue. In a way, Ernest Wright had been a victim of small success: in 2016, it had run a crowdfunding appeal to restart production of a classic model of kitchen scissors called the Kutrite. The Kickstarter went viral and a flood of orders came in, which the company struggled and failed to meet. Jacobs had been one of the 2000 or so backers, most of whom never received their scissors.

Saddened to hear of the company’s demise, he and his partner decided to buy the Ernest Wright brand, its IP and machinery; to renew the lease on its premises, and to revive the business. Jacobs and Fanoy upgraded the machinery, built a decent website, renovated the building. Jacobs told the local paper at the time, “We should not throw away good quality things and this is a good quality thing. In software it’s never tangible. I have no knowledge of making scissors. But I wanted a product I could feel and touch.” Ernest Wright is now a profitable concern again, serving people who love artisan scissors. I had no idea that such people existed; now I think I might be one of them.

Each pair of EW scissors is the result of at least seventy discrete processes. Craftland describes how the blades are “rumbled” smooth by porcelain beads, dried in a warm bath of maize and walnuts, and burnished with Italian cotton. Once the blades have been prepared by the “grinders”, they are passed to the most important people in the whole process: the ‘putter-togetherers’, or ‘putters’ for short. The putter connects and aligns each pair of blades.

When Jacobs and Fanoy took over, they rehired a handful of staff, including two veteran putter-togetherers with over a hundred years of experience between them. Eric Stones and Cliff Denton are still working, passing on their skills to younger craftsmen. It takes years to become a master putter-togetherer. Why - isn’t it just a matter of screwing two parts together? Well, no. Here’s Fox (who talks to one of the young putters, Neil Wilson):

A correctly assembled pair of scissors needs it bows aligned, its blades curved, its points crossing, the cutting tension firm and even all the way along. If these relationships are even marginally off, the scissors won’t cut properly. Such subtle calibrations can only be made by hand, once the two halves have been joined. To complicate matters further, every pair of blades is unique: a singular problem demanding a bespoke solution. “No machines can handle that,” Neil says. “You can’t even learn it in a book.”

You can’t learn it in a book. This is tacit knowledge. Of course, most scissors aren’t made to this standard and don’t need to be. But it’s interesting that the production of quality scissors is harder to automate than you might think. It reminds me of the debate over which jobs AI will displace. You can automate some jobs to a better standard, some to an an inferior but good-enough standard, and some won’t be automated for a long while yet. In the good-enough cases, there is still likely to be a premium sector, within which firms pay high wages for exceptionally skilled humans, whether in manufacturing or knowledge work or entertainment.

Many of the jobs we imagine to be straightforward, like truck-driving, have hidden complexity. This applies to the putter-togetherer, and not just in scissor-making. In the ad industry it was constantly predicted that account managers would become obsolete since they didn’t actually produce anything, but just ran around making sure that clients were happy and the agency team was doing its job.

But account people are still very much with us, since the good ones don’t simply pass along information or instruction but make finely calibrated judgements about people, in order to align the moving parts of a complex project - one which follows a template but is subtly different each time. You could say the same about many PAs and chiefs of staff and heads of operation. Putter-togetherers are everywhere, and they won’t be easily dispensed with.

This piece is free to read so feel free to share it.

‘What do you do?’ ‘I’m a bottom stainer’. At the back of Craftland is a long list of (mostly) extinct occupations, and it is quite glorious. I present a selection after the jump. Also after the jump: the online scam, aimed specifically at authors, that I nearly fell for. Plus thoughts on Carney’s speech; Andy Burnham; Hamnet; the commercial value of humanities degrees; why we read novels, and more. The Ruffian is an artisan, hand-crafted product which is dependent on paid subscriptions. Do sign up if you haven’t already, it’s quick and easy and cheap, and it will bring you many good things.