From Community To Tribe

When Real World Networks Are Replaced By Digital Ones

Catch-up service:

TikTok Can’t Take All the Blame For Populism

The BBC’s Friends Can Be Its Worst Enemies

Are Parents Too Close To Their Children?

Postcard From Venice

5 AI Failure Modes Shared By Humans

Why Are LLMs fixated on the number 7?

Successful Politicians Are Pattern-Breakers

I’m going to be talking John & Paul at Union Chapel in London on February 12th. Book now to guarantee disappointment.

I recently argued that teenagers are, if anything, spending too much time with their parents. Teens aren’t the only people who aren’t getting out enough. Much social commentary presumes that rising levels of depression and anxiety are the result of people struggling to form or maintain close relationships and feeling isolated. But maybe it’s the other way around: people have become over-dependent on intimates and are neglecting the wider world of face-to-face interactions.

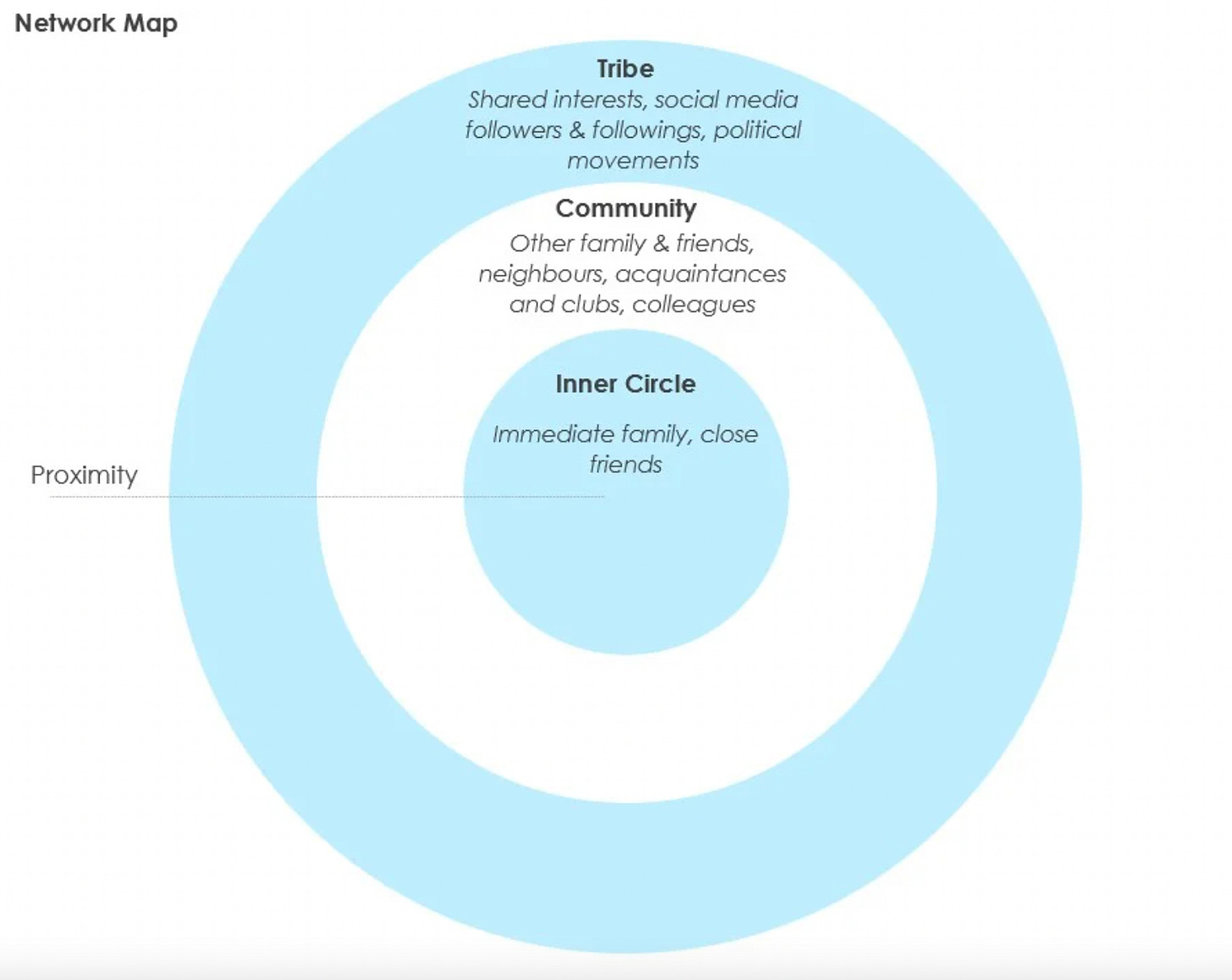

Sociologists talk about “strong ties” and “weak ties” - essentially, inner and outer social circles. Your strong ties are the people who know you well and who you depend on in a crisis - family and close friends. Weak ties are acquaintances: familiar faces in the neighbourhood, at work, and in third spaces like the café, pub, gym or shops. You may not know much about each other, but you will happily exchange greetings, gossip, or just a smile.

As anyone who remembers lockdown may recall, weak ties are important to our mental health. Collectively they give us a sense that the world out there is friendly and supportive. They also provide stimulation. Mark Granovetter, who coined the distinction, showed that people are more likely to get new information from weak ties, since close friends tend to know the same things you do (he found that people were more likely to find jobs through casual contacts than close friends).

Our strong ties are in relatively good shape. Families are spending more time together. A UK government survey finds that 94% agree that there are people who would be there for them if needed, and 92% agree that if they want company there’s someone they can call. What we’re facing now is a crisis of weak ties; a deterioration in our real world outer circles. Tom Johnson, a trend consultant, draws on time-use data and other sources to conclude, “For many people there are simply changes in the types of people they spend time with. Immediate family, very close friends: yes. Colleagues, fellow commuters, casual acquaintances: no.”

The weak tie crisis has three principal causes, which interact with each other. First, the pandemic knocked us out of the habits which build weak tie networks - most importantly, going to work, but also visiting pubs, clubs, concerts, places of worship (In the US, Derek Thompson calls this the anti-social century). Second, a rise in the cost of living has made it feel more indulgent to go out. Third, phones, streaming and delivery services have made staying in more attractive, accelerating a trend that began long before the pandemic.

It’s not necessarily that we’re spending less time interacting with people we don’t know well. It’s that we’ve shifted those interactions online. People are spending less time in workplaces, social venues, civic groups, the high street, and more time in online groups organised around affinities and beliefs. To borrow Tom Johnson’s distinction, community is being replaced by tribe. Both are over-used and vague words, but I’m using them in specific ways here. Community is a real world network of weak ties; tribe is an online group of digital acquaintances organised around a shared interest or preoccupation.

Community and tribe offer two very different experiences of human interaction, with very different effects. That’s clearer now than it was earlier in the century, when they were assumed to be pretty much the same. In the nascence of mass internet adoption, tech optimists believed we were entering a golden age for weak ties (Granovetter himself has noted that over 90% of the citations of his original 1973 paper on weak ties came after 2000). The dream of Facebook and LinkedIn was a radical expansion of “human connection”. Online social encounters would supplement and even improve on physical ones by enabling people to maintain larger and more efficiently organised networks of friends and acquaintances.

That wasn’t entirely false. Social media does expand our circles and it does bring us new information and opportunities. I get a lot of intellectual stimulation from online networks and I’ve made real life friendships through them. But the techno-optimist vision failed to account for crucial differences between online networks and real world weak ties. Here are eight of them.

After the jump: the rest of this piece, plus a Rattle Bag of thoughts and links on the Clanchy affair; the most impressive politician in the country right now; the hidden rationality of cognitive biases; the glory of Gettysburg; some lovely new Beatles content; why a scare story about AI isn’t true; and an exciting album drop. Paid subscriptions make The Ruffian possible. Join our tribe!