How To Choose Your Nemesis

What Makes a Rivalry Productive?

Catch-up service:

My Ten Favourite Books of the Year

How To Push Back With a Smile

From Community To Tribe

TikTok Can’t Take All the Blame For Populism

The BBC’s Friends Can Be Its Worst Enemies

Are Parents Too Close To Their Children?

Postcard From Venice

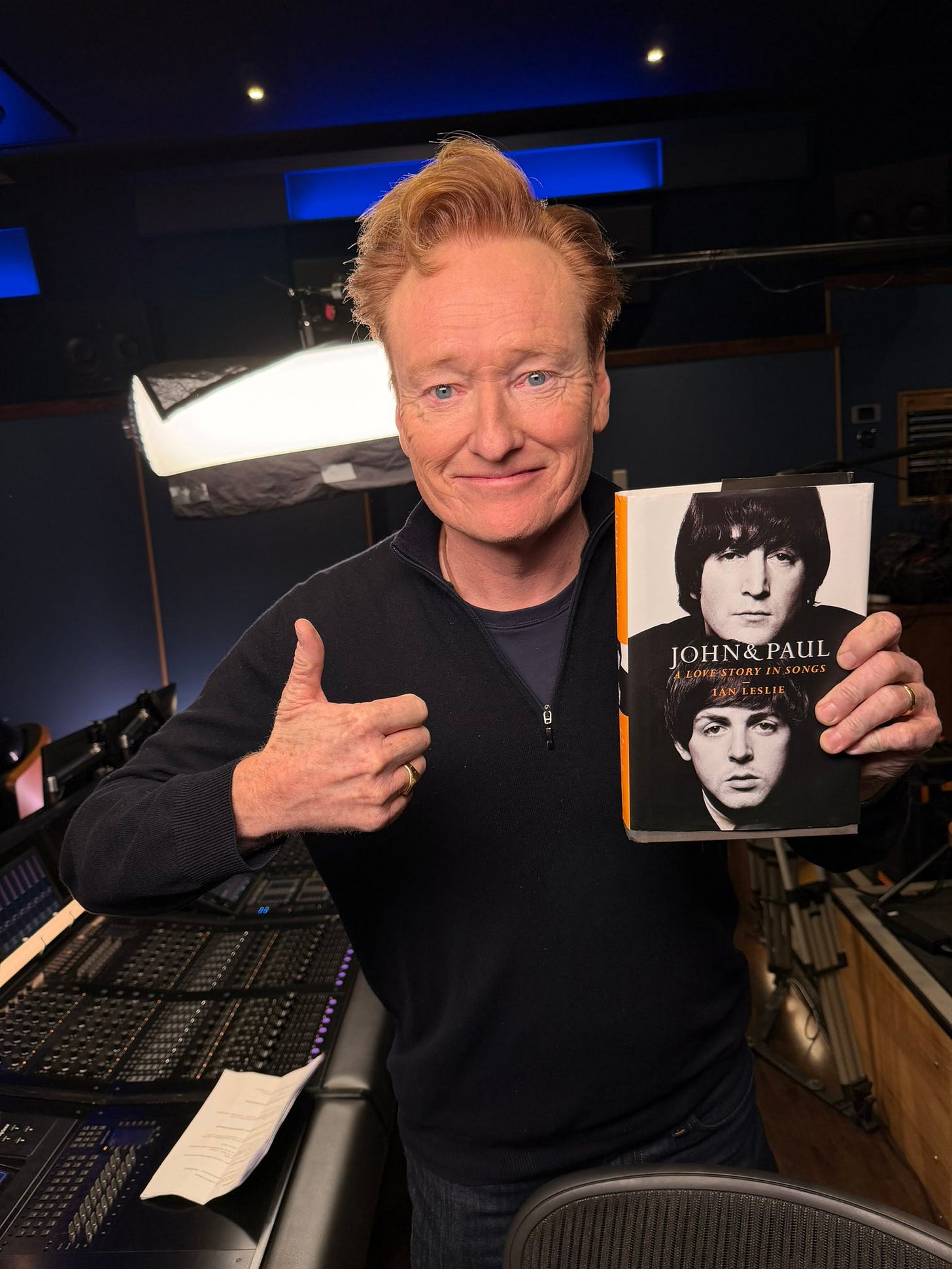

John & Paul is a book of the year in the New York Times, the Financial Times, The Times, The Economist, The Observer, NPR, and Kirkus Reviews. To find out why, get your copy from your retailer of choice.

John & Paul also gets a shout-out from Conan O’Brien (!) during a special episode of The Rest Is History on the Beatles. You can hear what Conan has to say about it here - although I recommend listening to the whole episode, it’s terrific. I’m a big fan of COB (and RIH) so this means a lot.

Finally: on Monday (Dec 8) my choir will be singing a selection of Christmas carols at St John’s Church, Hyde Park. It’s a varied programme of ancient carol and advent music and some familiar singalongs. Come along, it’s always a lovely occasion. Tickets available here.

This post is free to read - it’s nearly Christmas after all - so please do share and ‘like’ if you, well, like it.

How To Choose Your Nemesis

One morning in 1832, in a room in London’s Somerset House, artists were nervously preparing for the Royal Academy’s annual exhibition. This was “varnishing day”: a day when they could make final touches and oversee the hanging of their picture. John Constable’s large river pageant, The Opening of Waterloo Bridge, dominated one wall. Beside it was Joseph Turner’s Helvoetsluys, a Dutch seascape, rather subdued next to Constable’s work.

Constable was worrying over his painting when Turner came in, sized up the room, and, without saying a word, pressed a dab of bright red paint on to his canvas to make a buoy in the sea. Having added this attention-grabbing stroke, he left the building. Constable said to a friend, “He has been here and fired a gun.” The incident (dramatised in Mike Leigh’s film, Mr Turner) is recounted at a revelatory new Tate Britain show all about the rivalry between Turner and Constable.

The two artists were born one year apart: 1775 and 1776 respectively. By 1832 they were the most celebrated painters in Britain, and a study in contrasts. Turner was working-class, the son of a barber; Constable middle-class, son of a prosperous Suffolk miller. Turner was endlessly adventurous, always off to the Alps or Tuscany; Constable preferred to stay in England with his family. Turner was bold and experimental with a talent for spectacular effects; Constable more conventional, at least superficially, more concerned with accuracy of depiction. Critics referred to them as antitheses: fire and water, poetry and prose, the sublime and the beautiful.

The Tate does a good job of showing how these artists were as similar as they were different; both restless innovators; both endlessly fascinated by the play of light; both intent on capturing nature in the act by taking their palettes outside and braving the weather to paint and sketch what they saw (one of Turner’s sketches is mottled with raindrops). Both were outsiders to the medium in which they excelled - neither were trained as oil painters.

Despite a distant and occasionally acrimonious relationship, the two made each other better, producing a string of masterpieces in a dialogue that lasted over two decades. Constable, in particular, became a far greater, more ambitious artist than he would have been, as he sought to emulate the visual impact and grandeur of Turner’s work. Turner’s daub of red may have been an act of artistic aggression against a rival, but it was also a mark of respect, even kinship.

There are many such productive rivalries in the history of art: Michelangelo and Raphael, Picasso and Matisse, Pollock and de Kooning. Each comes with its own dynamics. Rivalries are also important in music (the Beatles and the Beach Boys), business (Jobs and Gates), and sport (Federer and Nadal). I’m sure you can name many more. Without wishing to make everything about my book WHICH MAKES AN EXCELLENT CHRISTMAS PRESENT the Beatles were propelled by internal rivalry, too. In fact, rivalry must be counted as one of one the most creative forces in human culture, and one of the most destructive.

Thr organisational psychologist Gavin Kilduff defines rivalry as a uniquely personal form of competition with heightened psychological stakes. In a rivalrous contest, victory is sweeter, defeat more painful. Kilduff offers three conditions for rivalry: the individuals, or teams, must be similar, evenly matched, and compete against each other repeatedly over time. His research suggests that rivalry is good for performance when it increases motivation. In a study of long-distance runners, he found that the presence of a rival increased a runner’s speed by five seconds per kilometre. (A 2022 review of the evidence to date confirmed that rivalry only has this kind of effect when it’s personal - many examples of ‘rivalry’ are just competition between strangers).

But rivalry has downsides, too. It increases the propensity of a competitor to engage in unethical behaviour - unsportsmanlike conduct, deception, brutal negotiation tactics. Nikola Tesla and Thomas Edison were Kilduffian rivals - both brilliant inventors and obsessively competitive. They competed directly over a period of years to prove their system of electrification superior; in “the war of the currents”, Tesla backed AC, Edison DC. Edison became so determined to crush Tesla that he tried to blacken his name and refused to accept Tesla’s idea had any potential when it clearly did (both systems are used today). The net effect of this rivalry was destructive: it probably delayed optimal electrification and wasted resources.

A lot of the scientific studies of rivalry have looked at sport, which is relatively amenable to measurement, but a new study in Management Science looks at knowledge work, specifically rivalries between software developers. The researchers found that rivalry also improves performance here too - but only among the most skilful.

The researchers analysed data from 4.6 million encounters on Topcoder, an online platform where programmers compete to solve algorithmic problems. In these weekly contests, entrants often find themselves matched with coders they’ve competed against repeatedly, making them rivals in the Kilduff sense (although for the most part they don’t know each other personally). Topcoder ranks programmers according to how well they perform, so the question of loss or gain of status is always present.

High-skilled competitors performed better when a rival was present, but rivalry made low-skilled coders worse. The reason seems to be a difference in attitude. High-skilled coders tend to be confident. Rivalry pumps them up. Low-skilled coders are more focused on preventing a loss. Rivalry makes them overly cautious. They choke. Separately, the researchers found that anyone close to losing status performs worse against a rival, regardless of skill level, because they worry about demotion.

So if you’re going to engage in rivalry with someone, it helps if you’re confident in your abilities and not overly anxious about a loss of status. If that holds, your rival will challenge and stretch you rather than petrify you. I can think of another condition for an ideal rivalry, too - that your competitor has something you lack and that you want. I don’t mean a material possession, but a quality or skill. When a rivalry involves some exchange of talents, it becomes non-zero-sum. Both partners gain and so does the world.

To explore this, let’s return to the realm of art. Since neither Turner or Constable spoke very much about the other on record, we don’t really know how much thought they devoted to each other’s work. But we can easily imagine that Turner envied Constable’s intimacy with nature and Constable envied Turner’s expressive freedom. Each saw something in the other’s work that they wished for in their own. In that sense, they were not merely rivals, but nemeses.

I’m borrowing that distinction from Ted Gioia, who argues that the most creative rivals aren’t enemies, even if acrimony creeps in from time to time. They are nemeses - competitors who mirror each other in some way, and who seek to learn from each other. An enemy wants to be different in every way from her counterpart; a nemesis seeks to be more like him in some way, in order to better them and themselves.

In an essay on Michelangelo, James Fenton cites a letter that Auden wrote to Stephen Spender in 1942: “You (at least I fancy so) can be jealous of someone else writing a good poem because it seems a rival strength. I’m not, because every good poem, of yours say, is a strength, which is put at my disposal.” Auden went on to say that this arose because Spender was strong and he, Auden, was weak, but in a fertile way.

This is how to think about the triumphantly non-zero-sum rivalry between Lennon and McCartney. Lennon admired McCartney’s gift for melody and harmony; McCartney admired Lennon’s emotional honesty and radical ideas. As I discuss in the book, neither of them was trying to prove he was better than the other. Both were trying come up with songs that bettered the other’s while drawing on each other to do so. As per Auden, they saw each other’s talents as strengths as their disposal.

Arguably, McCartney had more of that “fertile weakness” - a constant, acute awareness that others, Lennon included, were doing things of which he wasn’t yet capable, which made him want to do them too (though in his own way). It was McCartney who was driven wild with admiring envy by Pet Sounds. Lennon was a little more internally focused, somehow. This difference between the two of them was encapsulated by Ray Davies of the Kinks: '“McCartney was the most competitive person I’ve ever met. Lennon wasn’t competitive - he just thought everyone else was shit.”

Every productive rivalry is a kind of collaboration, and the best collaborations involve an element of rivalry. Which brings us, finally, to a crucial difference between painters and musicians. Musicians are predisposed to collaborate with each other in a way that painters are not. Imagine if Turner and Constable had formed a group together.

After the jump, a crunchy and juicy Rattle Bag: is Starmer just a pragmatist who can’t do vision? Hmm. Plus a terrific podcast on why British government is dysfunctional; the most significant economic news of the last two weeks; the finest appreciation of Tom Stoppard I’ve read; my thoughts on the movie Blue Moon; why poets are dangerous to AI; a brilliant business longread; some fantastic pop and jazz. If you haven’t yet take out a paid subscription, try it today and see what you’re missing. The Ruffian, which has no rival, relies on its subscribers. Thank you!