Ranters and ravers

The form of argument that defines our age, the truth about Dominic Cummings, and the usual goodie bag.

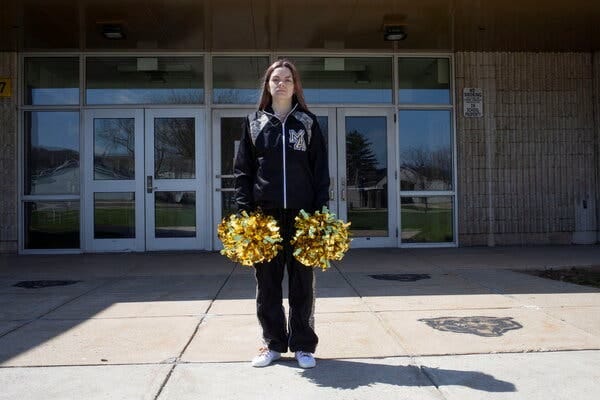

Brandi Levy. Danna Singer/A.C.L.U., via Reuters/NYT

One weekend in 2017, a Pennsylvania high school freshman called Brandi Levy opened Snapchat and expressed her fury at being passed over for the varsity cheerleading team. She posted a photo of herself and a friend giving the middle finger, with the caption Fuck you fuck softball fuck cheer fuck everything. Referring to the fact that another freshman had been given a place, she wrote, Love how me and [another student] get told we need a year of jv [junior varsity] before we make varsity but that’s doesn’t matter to anyone else?🙃

The rant went to about 250 of Levy’s friends on the app. One of them took a screenshot and showed it to her mother, who happened to be a coach on the cheerleading team. That was bad news for Levy. She was suspended from cheerleading for a year after being found in breach of rules which require that students show respect for the team, avoid “foul language”, and do nothing to tarnish the image of the school district. (If you’re not aware of how seriously cheerleading is taken in US schools, watch the fantastic Netflix documentary Cheer).

Levy wasn’t having it. Backed by the ACLU, she sued the school district, alleging a violation of free speech rights. She argued that since she didn’t post from the school campus or on school time, the school had no right penalise her merely for expressing emotions. Remarkably, the case went all the way to the Supreme Court, where it was discussed earlier this month. Although no decisive ruling was reached the judges seemed sceptical such a severe punishment was appropriate. “She’s competitive, she cares, she blew off steam like millions of other kids have when they’re disappointed about being cut from the high school team,” said Justice Kavanaugh. Justice Sotomayor asked the school’s lawyer, “You’re punishing her here because she went on the internet and cursed?”

The case touches on some fascinating and thorny questions like what kinds of speech should be punished (the judges discussed whether the posts counted as abuse or bullying) and whether schools have any right to police speech outside their physical boundaries. I tend to agree with the SCOTUS judges - I mean Premier League footballers do worse on Instagram and get off more lightly. But the main reason it intrigues me is do with how Levy expressed herself. Like millions of people do every day, she went online and ranted. Her aim was not to make an argument or to explain anything; it was to discharge an emotional load. She didn’t worry too much about what she was saying. She wasn’t instigating a dialogue. She just went for it.

Levy’s rant is a minor example of a major phenomenon. Rants are everywhere. We live in the age of rants. Snapchat posts; Twitter threads; TV clips that circulate endlessly on social media. In the rhetorical arsenal, the rant lies somewhere between a speech and a scream. It is a verbal eruption of anger, though the anger can be leavened with humour, simultaneously idealistic and snarky. A rant can be highly articulate, but it is not crafted or honed, at least it shouldn’t appear to be. It depends, for its force, on the appearance of spontaneity, of an author driving without brakes, laughing manically in the face of decorum and caution. The rant is, or claims to be, deeply honest. It is the mind being spoken with its censors turned off. The rant is the opposite of composed, in either sense; neither pre-meditated nor temperate. It is extravagant, excessive, too much. The rant is not an exercise in reason. It does not pretend to be nuanced or even-handed. It’s unashamedly, openly biased. It is also an act of belligerence: while a speech or an essay can be passionate, the rant has a violent undercurrent. It is an assault on an enemy, which may be a person or an idea or received wisdom.

Of course, rants are not a recent invention they are far from a purely online phenomenon. Demagogues and dictators rant to febrile crowds. A rant can be the highlight of a standup’s set (some comedians are natural ranters, some are not), or the dramatic climax of a film, or a mode of religious expression. The Ranters were one of those weird sects that proliferated in England in the middle of the seventeenth century as the Civil Wars rumbled on and the centre failed to hold. The Ranters rejected any external authority - church, scripture, government, army. All that counted was what you felt within.

The rant has finally met its historical moment, however. It is the form of argument which defines our era. We have a media ecosystem that has narrowed the gap between private thought and public speech; which triggers our subconscious impulses and bypasses our self-regulation; which elevates authentic self-expression over respect for norms; which incentivises outrage and stridency. No sooner have you thought fuck you fuck everything then can you say it to 250 or 2 million followers. The rant is not an argument in the sense of an adversarial dialogue; it invites no counterpoint. It is therefore perfect for a culture in which we stage performative public debates which are really exercises in avoiding disagreement and generating self-affirmation.

The rant is risky. The neuroscientist Stephen Caspar, who brought this topic to my attention, described the rant to me as a kind of “temporary insanity”, albeit one that is willed by the ranter. “In those moments you reveal something about yourself. It brings out this little Hobgoblin which wants to show everyone why you’re all morons. But if it’s completely uncontrolled you can end up saying a terrible thing that you didn’t even mean.” Brandi Levy didn’t expect to end up in court or expect to be haunted by this story down the years. Nonetheless, the risk is often worth it, because a good rant is rewarding, emotionally and otherwise.

The payoffs have never been greater. If you want write a Twitter thread that gets widely retweeted, you should be either very funny or very angry or preferably both; what you shouldn’t be is nuanced, careful, self-doubting. If you want to a create a TV clip that goes viral, you should give the impression that you are sick of holding your tongue and just need to tell it like it is. If you want to be a political influencer, upload a daily rant to YouTube and let rip. All that matters is that you give voice to what you and your audience feel, and that you include a donate button.

Please remember to spread the word about The Ruffian! It’s free to read but not free to produce. Please share this link.

Oh and please buy my book on healthy conflict and productive disagreement. Malcolm Gladwell says it’s “Beautifully argued. Desperately needed.”

DOM BOMB

Speaking of ranters. This week the Prime Minister’s former chief adviser Dominic Cummings gave evidence to a parliamentary committee on the government’s handling of the pandemic during 2020. Over the course of seven hours, he described in unsparing detail how the whole government failed to get to grips with the impending crisis early in 2020 and then scrambled to catch up, impeded by a hapless Prime Minister. Thoughts:

That was astonishing testimony. I think it was probably unprecedented and not just in terms of parliamentary evidence. Can you think of any major organisational screw-up in which a leading player so eagerly detailed his own failings, as well as those of his former colleagues? This was not “mistakes were made”. This was a rare example of someone saying, “I screwed up. I was not up to the task. I shouldn’t have been there.” He was right on all counts, more so than he knows, but we should at least give him credit for emphatically admitting culpability and for apologising to those affected, which he did repeatedly and to my eyes sincerely - I think he really feels the burden of it. I didn’t get the sense of someone trying to save face or thinking about his next job (he knows very well he’ll never work in government again). He really did want to put it all out there, almost as penance.

He performed a few drive-bys while he was at it. Since he couldn’t help but snipe at targets and push favourites, much of the coverage has understandably been about individuals. But what was really fascinating about Cummings’s testimony was the portrait it painted of wider failures. In his best moments he described a system and its senior decision-makers failing each other. The reason his evidence on this front was so compelling is not because his analysis of the British state’s problems is original or that his solutions are viable (at one point he suggested that in the next crisis a scientist should be given “kingly authority”- um, no), it’s that he is such a good storyteller. I’ve never seen someone narrate, in such colour, the experience of being at the centre of a government as it wakes up to the awful truth that a storm has hit and it doesn’t have a clue what to do. The vignette of a senior civil servant walking into to see him and the PM to say, “We’re fucked. There is no plan,” was unforgettable. His imagery - the spidermen, the shopping trolley - is vivid. There are clear cut heroes and villains. His delivery is magnetic - he made everyone else in the room seem pale and drab to the point of invisibility. The storytelling has public value, in this context. It is one thing to read weighty papers proposing civil service reform; it’s quite another to convey a feel for what it’s like to be inside the system, at its centre, as things slide out of control. So I think the narration was an important aspect of his testimony. It made the abstract idea of system failure feel horribly real.

That civil servant acted heroically. It takes guts to go and tell the Prime Minister the bad news to his face when everyone else is pretending the emperor’s clothes look just fine. It’s interesting that it took someone prepared to dispense with niceties for things to change. Direct, forceful speech seems to be a rarity in government, even in a crisis. Not once did Cummings describe a meeting in which people actually spoke their minds and challenged and argued in the room. The meetings seem to have been polite and dutiful and and pointless, with everyone deferring to “the science” even as we all read about people dying in Italian hospitals. Dissenting opinions were confined to corridors and WhatsApp chats. That allowed a zombie consensus about the nature of the pandemic to sustain itself way beyond the point at which anyone believed in it.

Cummings was remarkably open and, to my eyes, honest, yet it’s also true that he is a somewhat unreliable witness to reality. He spoke about the system failures of No.10 as if he was altogether detached from them. But if there was nobody exerting authority, no clear lines of command, that was in large part his fault. That was the missing mea culpa (he did, to be fair, begin to correct for it in the autumn by installing a Covid task force at No.10). He takes responsibility but does not fully grasp his own part in the failure.

His account of the Barnard Castle trip was a hot mess: melodramatic, confusing and self-contradictory. This was not, I don’t think, because he was trying to “hide the truth”, but because he was experiencing his own internal system fail. What seems to have happened last May is that he basically went a bit mad, and understandably so: he was under immense psychological pressure, intensely aware that he had screwed up on a massive scale, feeling horribly out of his depth, and worried about his family. I suspect he’s still in a kind of post-traumatic phase from the whole year, which is why watching him on Wednesday sometimes felt uncomfortably like being a voyeur at a therapy session.

Once someone goes through his testimony carefully I suspect they will find quite a few instances where what he said is misleading or just false. It’s not that he’s lying. I don’t know quite what it is, but something in the way his mind works means he doesn’t see things straight - I mean, even more so than most of us. It’s ironic that he is a fan of rationalists like Julia Galef, because his temperament and cognitive style is obviously at odds with their’s, evident in his writing as well as his speech (for one thing rationalists do not hit the caps key with such abandon; they don’t rant). Perhaps the talent for narration and the deeply skewed take on reality are two sides of the same coin. He lives inside his stories.

Cummings is reputed to be brilliant but difficult, yet when it comes to governing he is plainly incompetent and difficult; incapable of the basics, like running meetings, shaping processes, building alliances, finding workable compromises; dealing with people as they are not as characters in a play. He seemed to spend most of 2020 avoiding real responsibility and searching out distractions. Yes, the pandemic exposed pre-existing system failures, the principal one being a failure to properly interrogate the pandemic plan that wasn’t. But those failures were exacerbated by the fact that Cummings was the wrong man at the wrong time - which of course applies even more so to the man who put him there. As one official put it to me yesterday, “The system and officials can probably cope if you have a duff PM, but it can’t cope if both the PM and their most powerful adviser are incapable.”

MISCELLANY

It only exists in theory but in theory it’s a jumbo jet which reduces fuel consumption by 70% and it has THREE SETS OF WINGS.

Damian Counsell has constructed a methodically argued excoriation of the Sewell Report’s critics.

Excellent interview with Marxist sociologist Adolph Reed, who nails the problem with US discourse on race.

“On average, people in more individualist countries donate more money, more blood, more bone marrow and more organs. They more often help others in need and treat nonhuman animals more humanely.”

WHAT I’M READING

White Noise by Don DeLillo. For sure it’s one of the great American novels about late twentieth century capitalism but the main thing is it’s so funny. It made me laugh on pretty much every page. Its sly, ironic humour is interspersed with passages of straight-ahead lyrical beauty; moving descriptions of life’s minor miracles, like watching children sleep. Recommended! (Oh and read this annotation of its first page which contains some lessons in how good writing happens.)

QUOTE OF THE WEEK

”A neurosis is a secret you don’t know you’re keeping.” Kenneth Tynan

How to buy CONFLICTED - links to your favourite booksellers (UK and US).