Seven Lessons In Innovation From Dick Fosbury

The boy who dared to zig when everyone else zagged

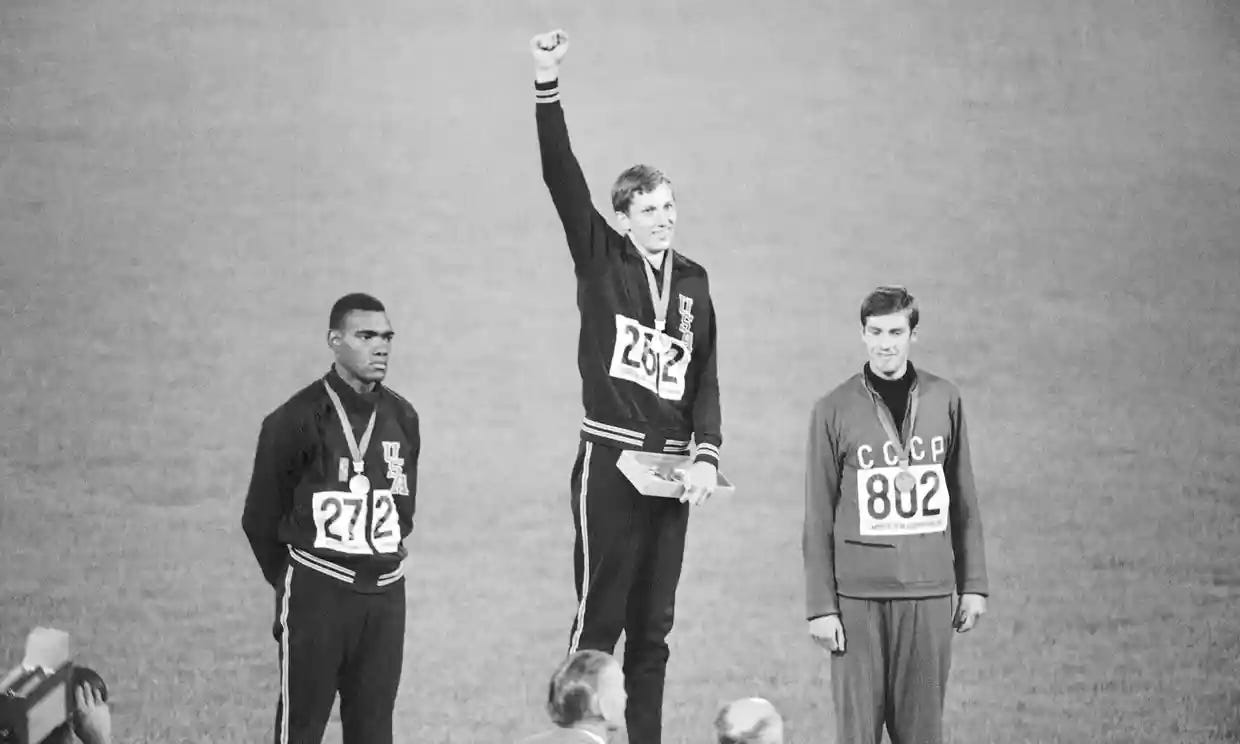

Dick Fosbury passed away this month, at the age of 76. Fosbury was a legendary athlete of a highly unusual kind. He did not dominate his sport for years or put together a long record of championship victories. He came out of nowhere to win Olympic gold at the 1968 Olympics in Mexico - and that was that. He didn’t win any other tournaments. He didn’t even qualify for the 1972 Olympics, by which time most jumpers were using the technique he invented. Fosbury was not physically gifted, at least in comparison to his peers, and he did not work particularly hard (by his own admission). Yet he reached the pinnacle of world sport and became one of the most influential athletes of all time.

I mention his shortcomings not to diminish his achievement but to celebrate it. Dick Fosbury shouldn’t have been anywhere near the Olympic podium. He got there through ingenuity, persistence, and strength of character.

Here are seven lessons to take from his story.

If you’re bad at something, maybe you can be good in a different way. Fosbury grew up in Oregon, son of Doug, a trucker, and Helen, a secretary who was also a concert pianist. At high school, he grew tall, but not strong, and he was not considered to have much athletic potential. After he failed to make the basketball and football teams, a coach suggested he try the high jump. That didn’t go well either. Fosbury was too lanky to co-ordinate the complex movements required to make a straddle jump, one of the dominant techniques at the time (see below) and struggled with the one he used, the “scissors” jump.

He kept losing competitions. In fact, Fosbury recalled being “the worst jumper in the school, in the school’s league, and in all of Oregon”. But instead of giving up because he was bad, he started figuring out a different way to be good.

Listen to your failures. Aged 16, Fosbury began experimenting with back-first jumps. Nobody put him on to this; he came up with it himself. At a track competition in 1963, he noticed that he was knocking off the bar with his rear end. This must have happened before, but this time he paid attention to it. People often say that when you fail you should wipe the failure from your mind, pick yourself up and start again. But sometimes you need to linger on your failures; to listen to them. They might be hinting at a different route to success. If Fosbury couldn’t solve his problem by lifting further off the ground, maybe he could lift his hips instead?

Be a thinkerer. As Fosbury worked on his backwards technique, he found himself moving his body more and more sideways, until finally he was jumping with his back to the bar, head and torso parallel to the ground, legs perpendicular to it. As his upper body went over, he learnt to kick his legs high and land on his shoulders. The jump began to describe a parabola. Innovations are often talked about as lightbulb moments - flashes of insight which transform everything. Sometimes they are. More often, they are the result of what Steven Johnson calls a “slow hunch”: an intuition which the innovator doggedly pursues over an extended period of time, iterating, experimenting and tweaking until they get it right. Fosbury didn’t discover a new way of jumping and immediately become a world-beater. It took him two years to teach himself how to clear the bar in a way that meant didn’t need to jump as high as his competitors. Two years of jumping and thinking, tweaking, and jumping. In my book Curious, I used the term thinkering - tinkering and thinking - to describe this kind of process. Thinkerers deploy different kinds of intelligence at once, putting them in dialogue with each other. Intuition speaks to intellect; intellect listens, revises practice, modifies intuition.

Seize the adjacent possible. Some transformative innovations require small shifts in perspective, not big ones. I'm borrowing once more from Steven Johnson, who himself took the idea of “the adjacent possible” from the theoretical biologist Stuart Kauffman. In any given system, from a biosphere to an economy to a sporting event, there is the actual possible - all the available possibilities given the current configuration of abilities, tools and rules - and the adjacent possible: the breakthroughs that are sitting right next door, waiting to be realised by someone alert enough to notice them. The adjacent possible expands in response to the actual possible. Even a small change in technology, for instance, opens up new possibilities which aren’t immediately apparent. High jumpers had always landed in a pit of sand or sawdust. Anyone trying to do a flop jump into a sawdust pit would have risked breaking their neck. It wasn’t a possibility worth considering. In the 1960s, foam rubber replaced the pits. Fosbury was the first to seize the new adjacent possible.

Stretch the rules. At Oregon State University, Fosbury’s college coach tried to get him to revert to a more conventional technique but reluctantly let him stick with the flop. Then in 1967, Fosbury broke the university’s record. The next year, he won the national college title, and U.S. Olympic trials. He had achieved lift-off. Part of the reason his coaches had objected to his jumping style is that they weren’t sure if it was legal, and now that he was winning competitions, opposing coaches accused him of breaking the rules. But Fosbury knew he wasn’t. He was stretching the rules, finding the give in them, looking for the between-spaces others hadn’t seen. Innovations in sport often begin this way. They only look like rule-breaking. The butterfly stroke was invented in 1933 when Henry Myers, a swimmer in a breaststroke competition, worked out he could go faster if he brought his arms over the water. Officials wanted to say it was a violation of the rules but couldn’t work out how it was. Eventually they decided to give it a competition of its own. In 1980, an unknown amateur table tennis player from Bolton, called John Hilton, became champion of Europe. He was assisted by a revolutionary bat with different rubbers on each side: one side spinny, the other side antispin. Since both sides were black, his opponents were bamboozled, unable to guess how the ball was going to come back at them from shot to shot. It felt like cheating but it was perfectly legal. Combination bats are standard now. (In response to Hilton’s victory the authorities changed the rules so that either side of a bat must have different colours).

Don’t trust experts. When you read about Fosbury’s story, you start to wonder how he stuck it out when everyone who knew what they were talking about told him he was doing it wrong. Most of us would have assumed they were right and given up. But Fosbury kept working on his idea. Once he became successful, the coaches at Oregon State watched films of Fosbury’s jumps, trying to work out exactly what he was doing so that others could duplicate it. It took them a long time to work out what this kid had worked out for himself. Fosbury didn’t know how to explain it either; he just knew it worked for him, and that the conventional techniques did not. It would be an exaggeration to say that innovators shouldn’t trust experts, who are right more often than they’re wrong. But innovators interrogate the expert position rather than accepting it unthinkingly. To adapt Ronald Reagan’s maxim for dealing with the Soviet Union: trust, but question.

Don’t be afraid to be weird. This might be the most important one of all. Fosbury’s persistence with back-jumping over the years when he was working out his technique is truly remarkable. It’s not just that his coaches were sceptical about it, or that it was anomalous, it’s that it looked weird - odd, ungainly, undignified somehow. You can imagine the jeering from spectators and competitors. “Everyone laughed at me,” he recalled. Up until his great success, there was a perennial tone of amusement, verging on ridicule, in reports on him. One paper compared Fosbury’s jumps to “a guy being pushed out of a 30-storey window”. Another called him “a fish flopping into a boat”. Fosbury was unconventional in other ways too. He was introverted, quiet and thoughtful, a skinny kid who wore mismatched running shoes. Before a jump he spent an unusually long time psyching himself up, rocking back and forth on his feet, talking to himself. Once, he pondered for four and a half minutes before approaching the bar.

For most of us, and for teenagers especially, being thought of as silly or weird is one of our greatest fears. It’s something we’ll do almost anything to avoid, even if that means giving up on our best ideas. But Fosbury had an extraordinary ability to make himself immune to the noise of derision and ridicule. To understand where that came from it helps to know a bit more about his early life. One Saturday in 1961, when Dick was fourteen, he and his ten-year-old brother Greg were out riding their bikes at dusk, when a drunk driver crashed into Greg, killing him instantly. Dick lost his brother, and then he lost his parents: Doug and Helen’s marriage did not survive this shattering event. Within a year they separated, and then divorced. Cut up, angry and depressed, unable to share his pain with anyone, Dick Fosbury threw himself into his chosen sport, in his chosen way.

Childhood bereavement plays a part in the stories of many remarkable men and women. It can create an emotional void, or lack, which they make a superhuman effort to fill with achievements. There is an element of that in Fosbury’s story - he talked about how desperate he became to “stay on the team”. But trauma can also create strength. Fosbury had skinny arms; mentally, he was as strong as Samson. Having experienced one of the worst things anyone can experience, he had much less to fear than most. He already felt profoundly different from most kids he knew. What did he care about jeering?

This post is free to read so please feel free to share.

I’m indebted to some excellent obituaries of Fosbury, including this one from the Guardian. I also drew from Bob Welch’s biography of Fosbury. Thanks to Ed Caesar and David Epstein for sparking my interest in Fosbury. Check out Steven Johnson’s newsletter.

I love a list. Who doesn’t love a list? Here are two of my other lists:

Seven Varieties of Stupidity

Ten Causes of Communication Breakdown

You can support the work of the Ruffian by signing up for a paid subscription, which is cheap and easy, and by booking me to give a talk to your organisation.

Great read. Have a talk a couple of years ago where I used him. The change from sawdust to a foam mattress was one I highlighted as well. Such a great story

This reminds (adjacently) of Conan Doyle's The Story of Spedegue's Dropper - about a young cricketer who tries out bowling the ball so high that it drops like a mortar onto the top of the stumps. Batsmen have no defence against it, and in short order he ends up playing for England against Australia - and being pivotal in winning. However, he never plays cricket again after that one match (doctors suggest his health isn't up to it)... though his technique didn't become adopted as Fosbury's was.

[https://www.arthur-conan-doyle.com/index.php/The_Story_of_Spedegue%27s_Dropper]