The Real Black Mirror

Why the best analogy for AI chatbots comes from sixteenth century magic

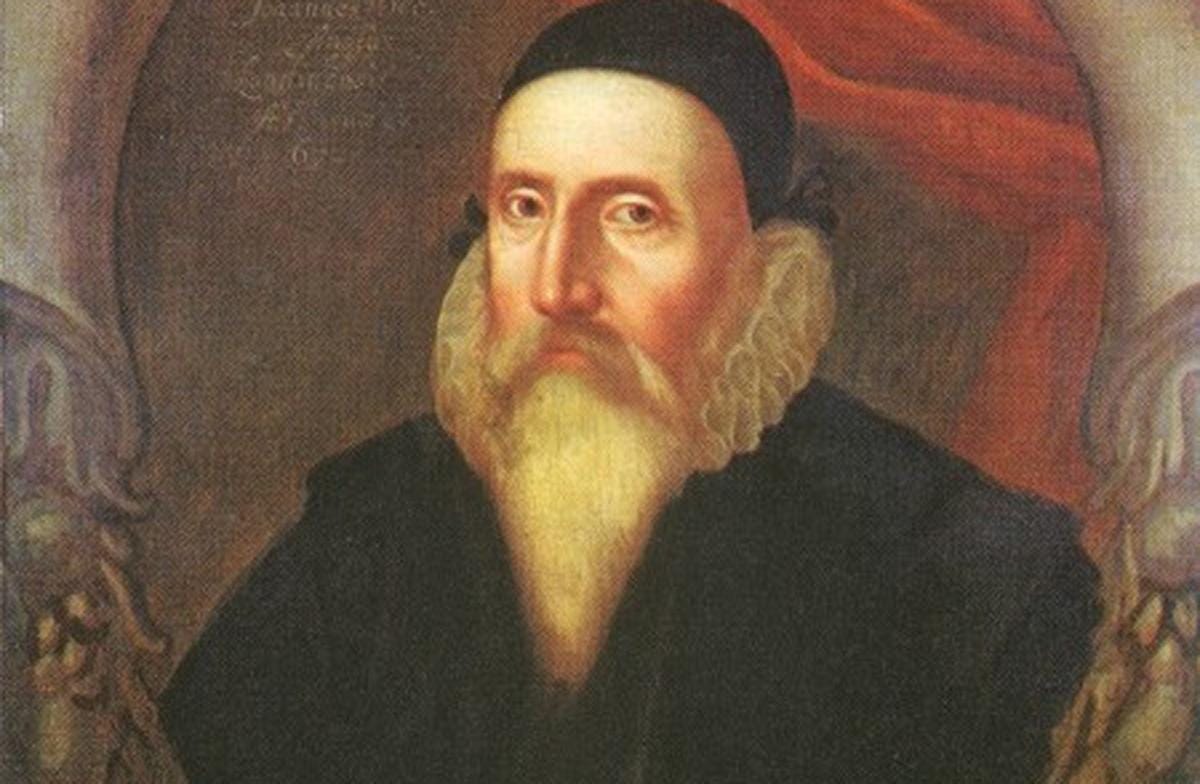

John Dee, mathematician and magus.

The title of Charlie Brooker’s show about technological dystopias evokes the shiny blank of an electronic screen at rest. I don’t know if Brooker meant to make an historical allusion, too. In the British Museum there is a round flat object with a black surface, made of obsidian: volcanic glass. When polished and lustrous, reflections may be seen in it. Black mirrors were used by Aztec priests to conjure visions and make prophesies. This one was brought to England in the early sixteenth century, courtesy of Cortez, where it came into the hands of John Dee, sage of the Elizabethan court.

Dee, who may have been the model for Prospero in The Tempest, was an influential counsellor to Queen Elizabeth and a European authority on mathematics, astronomy, navigation and cartography. He was a worldly man, who coined the phrase ‘British Empire’. He was also a kind of wizard, immersed in the occult - in numerology, astrology and alchemy. He used his black mirror to conjure visions, communicate with angels, and peer into the future. The magical side of his work was a source of fascination to Elizabeth but it sullied Dee’s name within and beyond the court. He was denounced as a conjuror of devils, perhaps a devil himself.

As his power at court declined, Dee became drawn deeper and deeper into the supernatural, which he believed could bring great benefit to mankind, although it sounds to me as if he was simply hooked on it. He teamed up with a rather dubious character called Edward Kelley who became his ‘scryer’ - the one who actually gazes into the ball or mirror and takes messages from spirits. Kelley dictated whole books of detailed prophecy, and they toured the grand houses of Europe together, holding séances. Dee practiced purifying religious rituals to ensure he only conjured good spirits rather than demons.

It was a strange world back then, and the world is getting strange again. In the often repeated words of Arthur C. Clarke, “any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic”. We usually take that to refer to the way tech can perform frictionless everyday miracles. I touch a screen and an image of my friend appears, and I can talk to her. That’s magical. But recent developments in AI have got me thinking about Clarke’s aphorism in another way.

In the world of sixteenth century England, magic was woven into everyday life like digital technology is now. Magic was not, however, a benign, user-friendly service, always ready to do our bidding. The spirits had agency of their own and they were unpredictable, capricious, judgemental. To summon them, to commune with them, might bring great insight and rich rewards but it was also fraught with danger. Magic was alluring, weird, and scary.

I feel differently about AI than I did even a month ago, when I last wrote about it. Back then, I was leaning towards the Gary Marcus view. Marcus argues that AI in its current form is merely simulating the ability to reason. It can’t think abstractly. It doesn’t distill general principles from examples in the way that humans do; it just matches patterns. Given a bit of information, it guesses what comes next, based on its vast corpus of training data. That’s why its essays are boilerplate or error-ridden or both; it has no concept of truth or falsity. “It’s just auto complete,” says Marcus, “and auto complete gives you bullshit.” The science fiction writer Ted Chiang calls ChatGPT “a blurry JPEG of the web.”

Marcus and Chiang make a good case for scepticism and I found it somewhat comforting. If this technology is just a mindless copyist, it may prove tremendously useful but it’s not going to be taking over the world anytime soon. However, AI researchers have been turning up some surprising results - results which suggest there is more to this story than Marcus and Chiang allow for.

After the jump, the weird curveballs that AI is throwing us and what has really changed my mind about it - plus what happened to John Dee. Sign up now and you’ll get access to this and last week’s essay on whether we should be raising children to be brilliant or happy plus all the other treasures behind the paywall.