The Struggle To Be Human

Machines are learning to imitate humans but humans are already imitating machines

What if Cezanne had visited Bali? An AI experiment from the Bali tourist board.

A few months ago Twitter was awash in weird art, now it thrums with verbal experiment. Yes, a new release from OpenAI has arrived, and instead of generating pictures, this one generates text.1 ChatGPT is a very fancy chatbot which can engage in conversation, write essays, make arguments - and conjure up follies at your command.

How to remove a peanut butter from a VCR, in the style of the King James Bible. A sonnet about Thomas Schelling’s theory of nuclear deterrence. Bohemian Rhapsody but about the life of a post-doctoral researcher. Less fun but no less impressive: here’s an answer to the question of how to solve the UK’s productivity puzzle; an essay on the measurement of poverty; an MBA-level paper on Toyota’s supply-chain management.

It is all quite dazzling. Of course, these are just the successful experiments, which obscure the many failed ones. We ought to be sceptical of the hype. Remember when everyone said Pokemon Go was about to change the world? (Not to mention that faded star, Alexa, which will probably turn up on the next series of I’m a Celebrity Get Me Out of Here.) But I suspect the release of ChatGPT will prove, in time, to be a considerably more important event than the release of Harry and Meghan’s Netflix show. What’s most striking is the speed of its progress. This iteration is clearly better than previous ones (themselves not too shabby) and a much more powerful version will apparently be along within months.

The academic who posted that ChatGPT essay on the measurement of poverty went on to note that while it’s impressive, it does resemble the kind of answers students give when they are winging it. This has been a common theme. The bot’s articles are fluent but tend towards the generic, bland and superficial. What we have here, for now at least, is a machine for generating plausible bullshit. That is not necessarily a bad thing. The road to new ideas is paved with bullshit. Anyone’s first draft is essentially a piece of bullshit; so is a free-wheeling conversation between collaborators. ChatGPT may prove be a useful tool in the early stage of a creative project, enabling us to get more quickly to better ideas. But for that to work, we would have to want better ideas.

At the moment, we too often settle for our own bullshit. In a thread provoked by the release of ChatGPT, the author and educator John Warner argues that the American education system no longer teaches students to write well but instead teaches them a series of rules for ‘good writing’. For instance, students learn to write essays which follow a five-paragraph template, without learning to think through the problem of structure. They are told which phrases can be used for transitions, and even the ‘correct’ number of sentences per paragraph, without being helped with how to write sentences worth reading. Algorithms substitute for thought. GPT3’s writing reads like bullshit because it has no idea what it's saying. It knows form but it doesn’t grasp content. That it resembles student essays should be a cause for alarm, but not because it indicates we’ve created a superintelligent being. As the philosopher Zena Hitz puts it, “The problem isn't that GPT3 looks like it can think. The problem is we stopped caring whether our students could think.”

We’re only beginning to figure out how AI will change society, and I will leave the prognostications to others for now. What I’m interested in is how humans have been laying the groundwork for bots to take over, even in areas where we are meant to be inimitable - in ideas, music, storytelling and democratic discourse. AI-generated culture and human-made culture are converging from both ends. As the machines learn how to emulate us, we are making it easier for them, by becoming more like the machines.

Robo-Pop

Bring to your mind, if you will, Every Breath You Take by The Police (bear with me). In the verses, Sting sings the title phrase and its variations over that deliberate, probing riff as the chords revolve around the root. There is pleading (Oh can’t you see…) but the song feels emotionally self-contained, as if the singer wants to say more but is holding himself back. Then the bridge arrives. The music changes key, and the singer unburdens himself: Since you’re gone/I’ve been lost/Without a trace…It’s the sound of someone revealing his wound, yet there’s a kind of giddiness to it, a sense of liberation. That key change is crucial to the emotional power of the song. It enacts the psychological release the singer is experiencing, so that we, as listeners, feel it too.

Key changes, and harmonic variety more generally, are a way of creating emotional complexity in pop songs. Changing the chords within the same key feels like a short journey; changing key feels like a visit to another town in the same country, a place where new possibilities throng the air. In pop, there’s a kind of cheap key change, sometimes known as a ‘gearshift’, often used towards the end of a track, when everything shifts up half a tone (see I Wanna Dance With Somebody, Livin’ On a Prayer and many others), but the most interesting key changes are more organic. They often come during the middle section - the bridge. The Beatles were masters of this. They first experimented with a key change in From Me To You, and before long, they were doing amazing things with their bridges, as in No Reply, where the mood suddenly shifts from misery to a kind of defiant optimism.

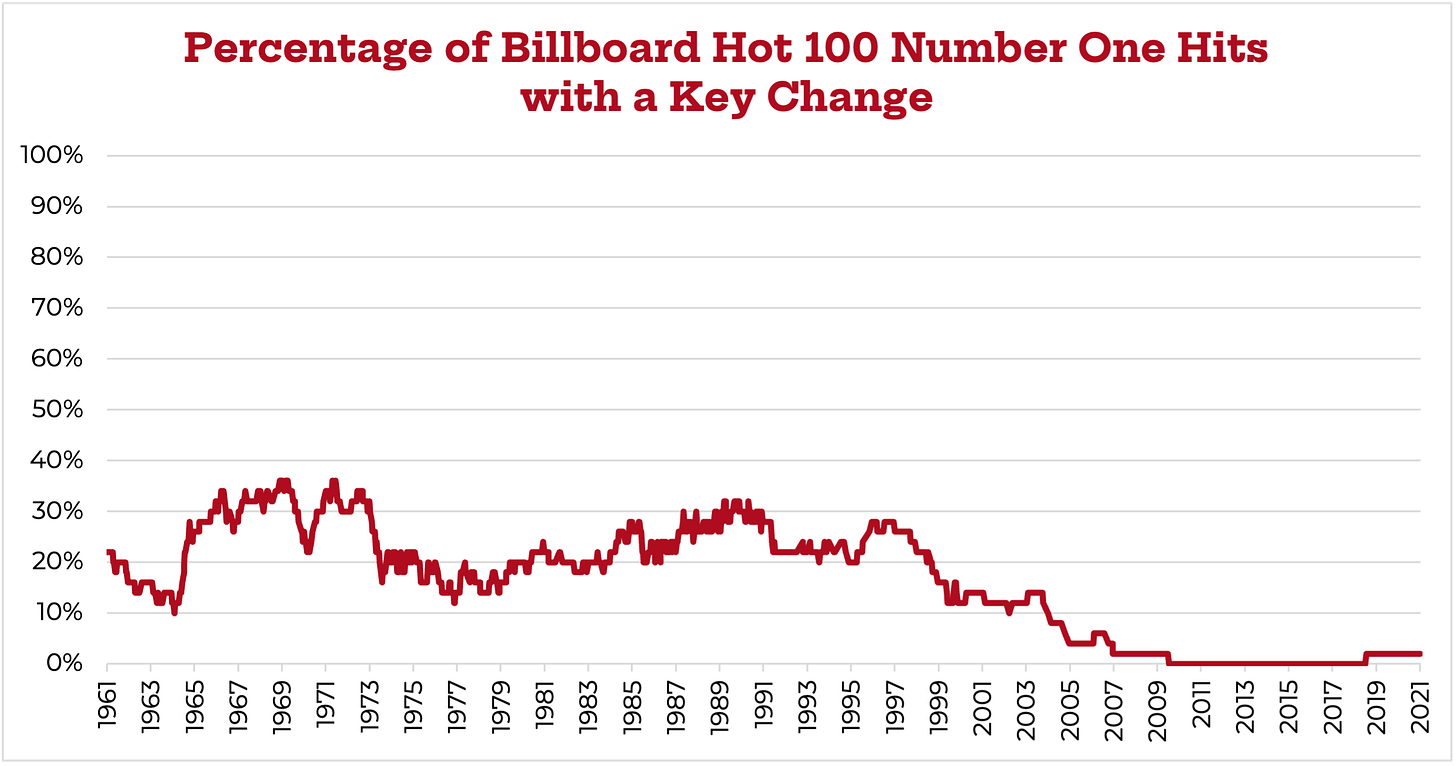

In recent years, the bridge has pretty much disappeared from pop. As it turns out, and perhaps not coincidentally, key changes have also become a lot less common:

On this chart I think you can see the effect of the Beatles pretty clearly after 1963, a late-seventies dip as punk arrives (yes, I am speculating wildly), and then another rise in the eighties and nineties, driven partly by those gearshift semitone changes but also because some of the rock bands at the end of the century, like Radiohead and Nirvana, were creating harmonically sophisticated songs. Then the key change falls off a cliff.

According to the piece where I found that chart there’s more than one reason for this. One is the rise of hip-hop, which is more about rhythmic and sonic complexity than harmonic variation. Another is that songwriters write on screens, using software with all the tracks (drums, bass, guitar) layered on top of each other, so they tend to think vertically rather than linearly. Instead of asking, ‘Where do I go from here?’, as you might do when using older technologies like the piano or guitar, they focus on, ‘What layer should I add or subtract?’ The musical and emotional narrative of a song becomes less important.

Another reason is that creators are making music that will be a hit on Spotify and other algorithmic services. Spotify uses machine learning to identify what kinds of songs are successful at winning user attention at the moment, then they push songs which conform the model to the top of the queue by adding them to playlists. The result is a penalty for complexity, variation and surprise - for anything the algorithm may not recognise. A feedback loop ensues, as musicians respond by creating songs to fit the model, and everyone herds towards the latest trend.

Modern song structures are simpler, more minimalist, and more predictable. They are shorter and get to the chorus quicker, since the data shows that listeners are impatient and click to the next track if they’re not immediately blown away (TikTok, a major platform for music, heavily favours short). The music writer Ted Gioia calls it “the robot aesthetic”. Rick Beato, a boomer musician who gives very popular informal lectures on YouTube, has a long but entertaining rant about the lack of variation in current music, showing his working on the guitar. Every song on the radio, he says, uses the same four or five basic chords. It’s boring. “We are living in an era of regression of musical innovation.” As Beato observes, this is odd, since we’re also in an era when more people can more easily access the endless variety of musical forms.

There are plenty of exceptions to this trend. Taylor Swift is a master of the bridge (see here or here). Leave the Door Open, by Bruno Mars and Anderson .Paak, one of the biggest hits of 2021, slinks and sashays through jazzy modulations (though, note, it is deliberately aiming to sound like a song from an older era). But overall, there are fewer bridges and fewer key changes and just less harmonic and emotional complexity. Music is being created to fit data-based models selected for us by the machines. The result is a flattening of affect, and a narrowing of horizons.

Key changes, bridges - these are rough proxies for the sensation of a song going somewhere that you weren’t expecting, and by doing so, enacting a shift in consciousness, a psychic emancipation. Sting himself has spoken about this eloquently. In an interview with Beato he notes, with sadness, the disappearance of the bridge from modern pop. He says that, for him, “the bridge is therapy.” In contemporary, bridge-less pop, “You’re in a circular trap. It goes round and round. It fits nicely into the next song and the next song. But you’re not getting that release - that sense that there is a way out of our crisis. And we are in crisis, the world is in crisis…I’m not looking to music to just reiterate my problem; I want to see how to get out of it.”

Even on a song which is deliberately harmonically simple, the bridge can create a bracing change of perspective. James Brown, having locked us into his groove, taunts us with the prospect of release (‘Can I take it to the bridge?’). Then, boom: he flicks the switch and suddenly anything seems possible.

Moneyball Movies

If pop is getting simpler, more formulaic, more machine-like, it’s far from the only only domain of cultural activity to do so. In Hollywood, it’s no longer true that “nobody knows anything”. As Derek Thompson writes in the Atlantic, the movies, like baseball, now run on data analytics. Studios use data to identify talent and evaluate storylines. They define what audiences respond to and then hone techniques for delivering it. And it works. Thompson says, “blockbuster movies look a lot like a solved equation”:

In 2019, the 10 biggest films by domestic box office included two Marvel sequels, two animated-film sequels, a reboot of a ’90s blockbuster, and a Batman spin-off. In 2022, the 10 biggest films by domestic box office included two Marvel sequels, one animated-film sequel, a reboot of a ’90s blockbuster, and a Batman spin-off.

In the world of movies, the blockbuster franchise has achieved something like the role Fukuyama proposed for liberal democracy in The End of History: the final answer. A franchise is a template, a structure and a set of rules which can be endlessly iterated on. The best franchise movies achieve this with tremendous skill, wit, and ingenuity, but there is a limit to how much of the human experience any template can capture. Martin Scorsese’s rather mild remarks about Marvel provoked a furore, a few years ago. They are worth revisiting:

For me…cinema was about revelation — aesthetic, emotional and spiritual revelation. It was about characters — the complexity of people and their contradictory and sometimes paradoxical natures, the way they can hurt one another and love one another and suddenly come face to face with themselves. It was about confronting the unexpected on the screen and in the life it dramatised and interpreted, and enlarging the sense of what was possible in the art form.

Scorsese observes that Hitchcock movies were thrilling, splashy mass entertainments but there was also a deeply human element to them which means they are still fascinating sixty years later. Hitchcock films may have had a certain sameness to them, “But the sameness of today’s franchise pictures is something else again…The pictures are made to satisfy a specific set of demands, and they are designed as variations on a finite number of themes.”

When we watch a veteran movie star like Keanu Reeves or Julia Roberts, the story of who they are, as stars, and as people, is part of the story. We feel a human connection to them, flaws and all, as if we’ve known them all our lives. Franchises come packed with stars, but stars are no longer characters in their own right, something Wesley Morris recently mused on: “The real stars now are intellectual property…Thor, not Chris Hemsworth. Spider-Man as opposed to Tom Holland or Andrew Garfield or Tobey Maguire.”

As with pop, there are many exceptions and subtleties I’m leaving out of this story. Rich, emotionally complex dramas as still being made. I recently watched Aftersun, one of the most deeply, in some ways painfully, human films I’ve ever seen. But the trend is clear, as are the commercial imperatives.

Robo-Democracy

Even politics has become more bot-like, driven by social media. Machine learning programs work by labelling objects and assigning them to categories. An image in a dataset either contains a car or it does not - it can’t be car-ish. The ontology comes pre-wrapped. This picture is either of a cat or of a sheep - it can’t be of a cat and a sheep. Nothing can be ambiguous and everything must be assigned a definite value. There is no room for doubt or uncertainty (as distinct from quantified variability).

Increasingly, political discourse, at least on social media, has the same qualities. In the U.S., voters have sorted into binary camps, blue and red. The prevailing orthodoxy on race has it that individuals and organisations are either racist, or anti-racist. Everyone must be either pro-woke or anti-woke. Each position has its ready-made scripts, defences and insults. When controversial news breaks, the tribes swoop and dive together, like starlings, only not so pretty to watch. It’s hard to resist the given line without seeming to take another given line. We all get pushed into boxes as if we’re being processed by a vast and implacable neural network.

On wokeness - anyone who is even sceptical of it feels pressure from both sides to declare themselves anti-woke, and to take those given lines, but that would be to defeat the point. I am woke-sceptical, and my primary objection to wokeness isn’t necessarily the substantive positions it implies but its formulaic and yes, robotic quality. In place of thinking or dialogue, certain phrases, buzzwords and narratives get learnt and then recycled mindlessly; liturgies devoid of spiritual content. Intersectionality, at least in its modern form, involves labelling individuals and sorting them into a series of overlapping identity categories, each with a certain value, so that everyone can be assigned their rightful position in a hierarchy of power. Complex relationships thereby get reduced to simple maths.2 The human qualities of imperfection, vagueness, forgiveness, laughter and love - everything that can’t be reduced to formula - have little role to play in this mechanical moral universe.

At the end of his very good book on AI and society, The Alignment Problem, Brian Christian (who also wrote The Most Human Human) concludes that although we are right to be concerned about the existential risks posed by intelligent robots running amok, there is a more immediate challenge to confront: “We are in danger of losing control of the world, not to AI or to machines as such but to models. To formal, often numerical specifications for what exists and for what we want.” He cites the artist Robert Irwin, who said, “Human beings living in and through structures become structures living in and through human beings.”

How can we avoid becoming structures, abstract entities with all the messiness of humanity scooped out? By taking seriously that which we cannot measure, and that which piques our interest but does not fit our models; by not being too confident in the models we have; by learning to appreciate ambiguity, intuition and mystery; by making room, now and again, for superstition and mad ideas. Above all, by refusing, in whatever game we’re playing, to make thoughtless and predictable moves just because they’re the moves we’ve been taught or conditioned to believe are the correct ones. We should strive to be difficult to model.

Such prescriptions mean very different things in different domains, of course, and this post is already too long, but much of it is to do with cultivating a unique sensibility or voice. ChatGPT has the information and skills to write decent articles, but its voice is by definition generic. Voice isn’t just a question of style. It is formed from what you choose to know and care about; from how you think as well as how you communicate. I wrote about it in my post, How To Be Influenced. The artist’s voice provides us with a handy metaphor for other kinds of creative endeavour, including the art of just being in the world. We can see that Bob Dylan, for example, never had the kind of voice that fitted any template for success, but that he somehow made that a strength. We can also see how much he strived to avoid being slotted into categories, to follow rules or be predictable. We can see that he made some mistakes along the way and that the mistakes were interesting. In other words, Dylan is a case study in the struggle to be human. There are many others.

Whether it’s music, movies or politics, we seem to be creating a world more amenable to AI by erasing more and more of what makes us, us. Even if we think we have got the better of this deal up until now, we shouldn’t assume we always will. A little resistance is prudent. The bar for being human has just been raised; the first thing we should do is stop lowering it.

This post is free to read and share, so please do!

THANK YOU to all of you who have read and shared the Ruffian this year. Please consider a paid subscription if you haven’t got one - that’s what enables me to keep this thing going. Plus you get access to exclusive Ruffian content. Speaking of which…

Next week, for paid subscribers only: my favourite books of the year, and a bumper goodie bag of other stuff I think you’ll enjoy. I may even do a bit of prognosticating. I’ll also have a stocking-filler for God Tier subscribers only.

OpenAI is a non-profit founded by Elon Musk to try and ensure that the most advanced AI is non-evil. There are a few other big centres of AI innovation, like Deep Mind, here in the UK. Hard for a non-expert to say which is the most advanced at the moment but what we do know is that OpenAI is the best at making its products user-friendly: it releases them with interfaces that enable anyone to play.

Teresa Bejan: “The crucial insight of intersectionality, as I understand it, is to remind us that none of the identity categories we use politically are homogenous monoliths, and that individuals are always differentially placed within these categories. That is the message I take from Kimberlé Crenshaw or Patricia Hill Collins. But now, that intersectional insight has become reified, in a way that says, well, certain people - in virtue of their intersectional identities - are placed in such a way that they have a kind of privileged access to knowledge that leads to a certain kind of social authority. Again, it's about wanting to imbue the identity with power or authority, as opposed to saying, well, individuals inhabit these different identities but these identities don’t define who they are - or what they have to say.”

Right on time and on the nail. Excellent post. Thank you.

Very interesting entry. One of those that will stay with me. Two thoughts:

1. The rise of "lines to take" for all manner of public facing entities (e.g. politicians) is surely in part a manifestation of the rise of data-driven/modelled decision making - to the extent the lines are formulated based on models of how messaging will be received. Maybe this leads to a similar effect as with Marvel films (i.e. perfectly satisfactory, but intentionally not introducing new or risky ideas), but in more obviously consequential terrain for wider society.

2. There are likely to be interesting second-order problems of relying on models to do our thinking for us e.g. a) we may become worse at making decisions where we can't form a useful model (because e.g. the situation is in some way unique or contains too many unknown or unidentified variables to be sufficiently tractable for formal modelling), or b) recognising when the model we're relying on is either simply wrong or being used wrongly (especially if we are partly using a model-driven approach to a skip debating what assumptions should go into it).