The Struggle With The Audience

What we can learn from artists about how to deal with other people's expectations

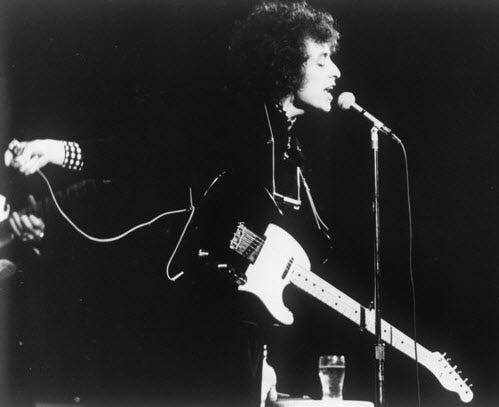

Bob Dylan, 1966.

What follows is a companion piece to my post from a few weeks ago, How To Be Influenced. It’s free to read (well, most of it).

Architects are a metalcore band from Brighton, on England’s south coast. I confess I hadn’t heard of Architects or indeed metalcore until I listened to an interview with the group’s lead singer, Sam Carter (on a Beatles podcast, of course). Still, I only had to listen once to their 2020 single, Animals, to understand why Architects are playing to twenty thousand people at the O2 this month. It’s muscular and aggressive and thrilling, with a huge, irresistible chorus.

Animals has twenty million views on YouTube. It’s the group’s most successful ever track. In the interview, Carter talks about the song as a turning point, creatively: it added a pop sheen and hookiness to the group’s heavy metal sound. Together with the album from which it comes, For Those Who Wish To Exist, it took Architects out of the genre niche in which they had successfully established themselves and into the arena-filling league.

You might have thought that the release of Animals would have been a happy event for Carter. In fact he recalls it as a painful one. Hardcore Architects’ fans - at least, the ones who posted comments online - were almost unanimous in their disdain for the new song: “It got absolutely slated - more than anything we ever did,” Carter says.

By 2020, Carter was a battle-hardened veteran of the music scene. He’d been making records with this group for twelve years, and Architects had had enough success not to worry too much about negative reactions to new material. It was also quickly apparent that Creatures was going to be a big hit. Despite all this, he found the reaction to hard to deal with: “It was doing huge numbers on the streaming services, but all I could see were these horrible comments.” On YouTube and Instagram, the negative reactions become increasingly extreme as people competed to make the most negative comment. “It’s hard, when you’ve put your heart and soul into something, and someone says, ‘I’m never listening to your band again, you’ve ruined it’.”

Carter then makes a striking assertion. If social media had come along earlier, he says, “Sergeant Pepper wouldn’t exist. The most important records of our time wouldn’t exist.”

Pop stars who make abrupt but successful left turns are highly celebrated. The Beatles and Bob Dylan were pioneers of this move and did it repeatedly. U2 did it with Achtung Baby, Radiohead with Kid A, The Arctic Monkeys with Tranquility Base Hotel & Casino. When it goes well, some fans resist the move (‘Judas!’) but others embrace it, and new fans join the party. The artist is reinvigorated, creatively and commercially.

But perhaps we underestimate how difficult these moves are, even for artists who appear supremely confident. Watch footage of Bob Dylan on his 1966 “electric” tour and he seems defiant and imperious as the audience heckles and jeers. I used to assume he relished the outrage. It wasn’t until recently, when I listened to Robbie Robertson, then a member of Dylan’s backing band, talk about the tour, that I realised quite how punishing it was. Robertson remembered it as a miserable time, for Dylan and for all of them. “People booed and threw stuff at us every night, everywhere we played,” he said. “We kept going, we played louder. But it was hurtful.”

Nobody else had been through this. It hadn’t happened before - to anyone. Stars entertained, fans applauded - that was the deal. It was utterly disorienting to have your own fans turn against you. Maybe they were right? At one point Robertson wondered if there was a problem with the sound, and asked a member of the crew to record one of the gigs. That night, Robertson, Dylan, and the others sat, demoralised, in a hotel room, listening to the tape of their show. Nobody said anything for a while, until Robertson spoke up. He said, “They’re wrong. They’re wrong. This is really good. The world is wrong and we’re right.”

The Dylan tour might just have signaled the birth of the empowered audience - a mass audience with clear expectations, which talks back when those expectations aren’t met, and demands to be listened to. Robertson’s little speech was the birth of a kind of resistance to it, in the name of creative self-expression.

In 2022 the same dynamic exists, except that the balance of power has shifted. Sam Carter suggests that it’s harder than ever for contemporary bands to break with the expectations of their audience. In a way, that’s surprising. This ought to be an age of innovation and exploration. It’s never been easier to record and share music and there is a seemingly infinite variety of available styles to ransack. But the ubiquity and virulence of online discourse is having a chilling effect on artists who want to try something different. Somehow we’ve created an environment in which artists feel an intense pressure to to stay in their lane. “Young bands are scared of making brave bold jumps because they’re terrified of being slaughtered,” says Carter. “It’s a psychological battle.”

It used to be critics who wielded the power to intimidate, but critics have been usurped by the online audience. Humbled, they no longer wield the knife so freely; Carter remarks that music writers tend to be supportive these days. Now, it’s the audience which has the whip hand. Pop stars have armies of fans online who are unwaveringly partisan, and clash by night with armies of haters. But the most adoring fans can behave, en masse, like an obsessive, controlling lover.

Th empowered audience does not just enforce conformity. In sport, the effect can be to force more rapid change. The football writer Michael Cox recently observed that English football managers get fired and replaced at a faster rate than ever before. The owners of Italian clubs used to have a reputation for being trigger happy; Italian football experts looked enviously at the patience of clubs in England, where managers were “as secure as civil servants”. But the turnover of English managers is now staggeringly high; any manager appointed before February 23rd this year is already in the top 50% of long-serving managers. Cox argues that one reason for this is that fans have become more impatient. When a team goes on a losing streak, they quickly turn against the manager and call for his sacking. The club’s management get scared and do what the audience is noisily demanding. Why are the fans so quick to anger? Cox thinks it’s to do with the non-stop nature of modern football consumption:

Once upon a time, you went to the match once a week, you watched highlights of the game, read a couple of newspaper articles about your side and chatted to a couple of friends, but that was pretty much it. You were then detached from the game. Today, if there is a general feeling of discontent with your club’s manager, it’s possible to be inundated with reminders about his struggles several times a day, through various sources. Fans can, if they choose, access non-stop opinion from fellow supporters about the manager’s struggles.

Cox refers to Cass Sunstein’s classic paper on “the law of group polarisation” - when a group of people who agree about a controversial issue get together and discuss it, they end up, individually and collectively, taking a more extreme position than the one they started with. They radicalise each other.

Sunstein’s paper was published in 1999, before the age of social media. We now witness the law of group polarisation playing out at scale, across many areas of public life. Football fans who get together in forums to discuss why a manager isn’t doing as well as they hoped come away convinced that he is disastrous and must be fired immediately. Music fans who are a little uncomfortable with the sound of their favourite act’s new single soon persuade each other that it’s an unforgivable betrayal.

During the Covid-19 pandemic, scientific experts acquired audiences on Twitter, often made up people predisposed to agree with their basic stance. Pessimists acquired pessimistic followers; optimists acquired optimists. These camps soon became markers of identity, just like pop stars or football clubs are for their fans. That in turn made the experts more rigid in thinking and coarser in expression, since the surest route to growing an audience was to cultivate its sense of righteousness. It’s not that the experts necessarily thought about it this way; they simply learned what felt rewarding what did not. To stray from the audience’s expectations was to invite harsh criticism and abuse. It was more gratifying, and less scary, to give the audience what it wanted.

Professor Oliver Johnson, a mathematician at Bristol University whose Twitter feed has been a bastion of calm clarity during the pandemic, resisted this dynamic, which he calls ‘audience capture’. But he found it difficult:

It's been very striking that going through so many waves has shifted the general mood back and forth, and it has required a determined effort not to be swung by the replies I've received. Followers that I'd acquired during downswings complained about doom-laden graphs when the numbers started to rise, and people who joined me while things were going up found me complacent when the plots were pointing down again. It's been hard not to be swayed by that. I could certainly see the temptation to pick a side (consciously or not) and tend towards more consistent optimism or pessimism. That might have become an even stronger issue if I had felt an obligation to provide an audience of paid subscribers the kind of content that they had signed up for, rather than just giving it away for free.

When we consider big political disruptions of recent years we tend to blame shadowy top-down forces: malign elites, Russian bots. But most of it can be explained by people who broadly agree talking each other into more radical positions, and then exerting pressure on elites. In 2015, Labour members who were uninspired by centrist leadership candidates persuaded each other that an eccentric far-left MP who had never sat on the front bench was just the ticket. In 2016, voters who were mildly unhappy about the EU persuaded each other that the only option was to leave it. This summer, Tory members spent hours on Facebook convincing each other that Liz Truss was the reincarnation of Margaret Thatcher.

To summarise, the modern audience is wilful, relentless, entitled, quick to judge, and prone to extreme opinions. It is a mercurial bully, and it’s the boss.

The next question, then, is how to manage upwards. Business leaders, celebrities and politicians are still learning how to handle the empowered audience (which in the case of businesses includes their own staff) - at coping with its demands, resisting it when necessary, while listening and learning from it at the same time. This isn’t just a challenge for elites, however. It’s a challenge faced by anyone who feels vulnerable to the expectations of others - which is to say, most of us. There’s perhaps a separate post to be written on how organisations should respond to these challenges; here I’m going to focus on individuals.

Social media users live their life in a spotlight which is part real, part imagined. As Chris Hayes put it in the New Yorker, the internet universalises “the psychological experience of fame”. These days, we all have an audience to please. It consists of the people we know are following us online, and of the strangers who might see what we post, an audience which may only be conceptual but which exerts a force on us nonetheless. Who knows who, or how many, might come across your next selfie, hot take, or video?

The anxiety generated by this omnipresent audience is acute for those who have yet to develop the inner resources necessary to cope with its demands. Teenagers and young adults, perhaps girls in particular, feel constantly subject to the gaze of multiple others of mysterious number, as in a reverse panopticon. They desire compliments, likes and shares, but even if they get them in abundance, they are haunted by their opposites: criticisms, withheld likes, zero shares. Perhaps that is true of anyone on social media, but young people are more likely to obsess over the opinions of others, since they haven’t worked out their opinion of themselves.

This tendency predates the internet, of course. In 1967, a developmental psychologist called David Elkind coined the term “imaginary audience” to describe how adolescent children see the world, or rather how they see the world seeing them. The idea is that teenagers are prone to mentally exaggerate the extent to which their behaviour and their bodies are under close surveillance by family, peers, and strangers. They feel as if everything they do and say is being evaluated and judged. This makes them nervous about expressing different versions of themselves, and increases their tendency to conform to group behaviour, and to participate in fads.

Well, somehow, we’ve created a world in which the imaginary audience is real. To adapt Joseph Heller, just because you’re paranoid doesn’t mean you aren’t being judged. The news about social media isn’t all bad, by any means: as a recent review of adolescent social media use argues, it can help teenagers feel less alone and strengthen relationships with peers. It can also be a channel for creative self-expression and experimentation. As with everything to do with the internet, much depends on how people use it; whether they master it as a tool or allow the tool to become a master.

These new ways of living have come upon us fast. We’re all working this stuff out as we go along, struggling to find the habits and skills we need to make the most of new technologies while defending ourselves from their adverse effects. The paradox of our hyper-connected, infinitely diverse culture is that it’s harder to be an individual than ever. The audience makes demands on us that we want to satisfy, either because it gives us gratification to do so, or because we’re scared of what it will do to us if we don’t.

I think we can look for models of how best to manage this strange relationship in the pre-internet world, as well as in the contemporary one. If something of the experience of fame is now universal, then we should be able to learn from those who have successfully negotiated the tension between self-cultivation and audience-pleasing over the last sixty years or so. In the next section I’ll look at a few different methods that artists have used in the struggle with the audience, with help from Dylan, the Beatles, David Bowie, and Glenn Gould.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Ruffian to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.