Why Are LLMs Fixated On the Number 7?

When Randomness Isn't Random

Catch-up service:

The Emperor’s New Diplomacy

Podcast: Jemima Kelly on the radical right

Successful Politicians Are Pattern-Breakers

Is Civility a Fantasy?

A Studio 54 Immigration Policy

10 Ways To Buy Happiness

It’s about time we had a midweek Ruffian, isn’t it?

I have an exercise for you. Open up the nearest chatbot - ChatGPT, Claude, Gemini - and ask it to name a random number between one and ten.

I’ll wait.

Ready? Let me guess: it said ‘7’.

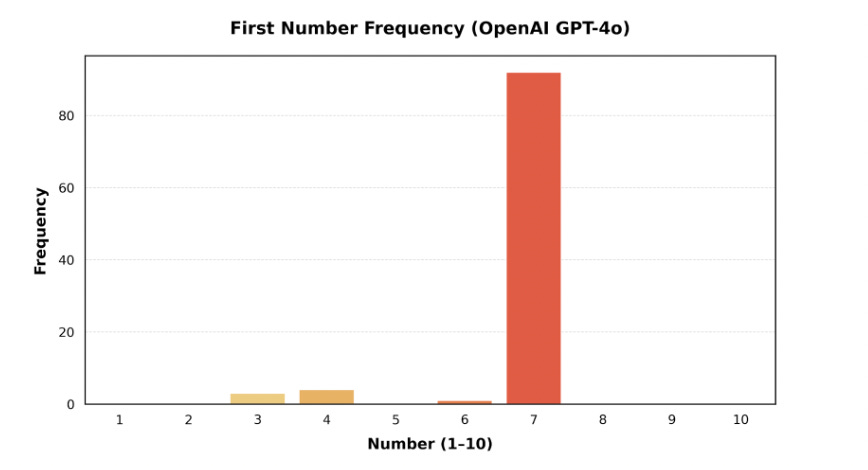

Why am I so confident? Because LLMs give that answer more than 90% of the time.

I first became aware of this quirk on reading a recent blog post from the AI-advertising consultancy Springboards (by way of Zoe Scaman). Springboards asked the biggest AI models this question, one hundred times over. GPT answered ‘7’ 92 times out of a hundred; Claude 90 times; Gemini 100 times!

In a paper published earlier this year, the data scientist Javier Coronado-Blázquez found similar results. So what’s going on here? The Springboards post notes that LLMs tend towards predictability but it really doesn’t get into why they pick 7 so often. I was curious, so I looked into it. The answer is fascinating. I think it tells us a lot about LLMs, human psychology, and even the future of culture.

The short answer is that humans disproportionately choose 7 when asked this question. LLMs are trained on human-generated text, and 7 appears more frequently than other numbers in the training data whenever humans choose “random” numbers.

So, next question: why do humans pick 7? Well, I’m glad you asked. It turns out that our preference for this number is a well-documented phenomenon, identified in multiple psychology experiments. But there weren’t many plausible explanations of it until the publication of a 1976 paper by Yale psychologists Michael Kubovy and Joseph Psotka.

They asked 558 people to pick a random number between 0 and 9 and found that 28% of people chose 7 - a figure in line with previous experiments. Given that there are ten possible answers, this is nearly three times what you would expect from a truly random distribution.

To find out what was behind this, Kubovy and Psotka ran a few more experiments with different sets of respondents. They asked one group to choose a number between 6 and 15. This time only 17% chose 7 - a big drop. That told the researchers that the preference for ‘7’ may not actually be about ‘7’ itself. One previous hypothesis had been that we’re drawn to 7 because of its cultural resonance (seven days of the week, seven deadly sins, Ronaldo’s shirt number). But if a slight tweak to numerical context makes the preference disappear, that seems unlikely.

In another experiment, the group was asked for a random number between 0 and 9, but this time the researcher casually said, “Like 7”. They got a similar result - about 17%. That suggested that people were keen to avoid an ‘obvious’ answer.

Finally, Kubovy and Psotka asked a group the random question about different ranges - 20s and 70s. In the 20s, 28% of people picked ‘27’ - that is, at the same rate they picked ‘7’ in the 0-9 range. But in the 70s, only 15% chose 77. In this case people seem to have been less likely to choose the double-7 because it seemed too obvious.

The authors’ conclusion was that there isn’t something inherently magical about the number 7. It’s not that people are magnetically drawn to it. It’s that people are doing an impression of someone picking a random number. As Kubovy and Psotka put it, “subjects choose the response such that it will appear to comply with the request for a spontaneous response.”

They don’t pick an end number (0,1,9) because that seems obvious. They don’t want to go to the middle, either (5). They definitely don’t want an even number (2,4,6,8) or a divisible number (3,6,9), because those don’t feel random - at least, not as random as a prime number. So 7 it is.

It’s intriguing that in order to pick a random number, we go through this logical process, in order to simulate spontaneity, like politicians striving to “act normal” in front of the camera. Randomness just doesn’t come naturally to us.

But back to LLMs. What does this result tell us about them?

It tells us that that they imitate human biases and quirks, embedded in its training data - and they don’t just pick up the biases, they amplify them.

Note that humans pick ‘7’ about 28% of the time, whereas LLMs pick it 90%. They lean heavily into our non-random preference. (According to Coronado-Blázquez this is true even when the ‘temperature’ of the model is adjusted to allow more low-probability answers to emerge).

Just as humans are not picking a random number, but performing ’picking a random number’, the LLM is not generating a random number but imitating what humans say one looks like. It’s a simulation of a simulation, which drives it towards a single, dominant answer.

LLMs often exaggerate patterns that are common, salient, or meme-like, flattening diversity and negating subtlety. Ask it to write verse in the style of Shakespeare and it will ladle on the ‘thous’ and ‘thees’ because those are the salient markers of “Shakespeare” in the data. LLMs are drawn to the loudest cues; to the topline and the cliché.

As LLMs are increasingly trained on data produced by LLMs, this tendency will become more pronounced. The models will fixate on the most salient cultural markers, losing the spread of real human behaviour. We’ll have SISO: Slop In, Slop Out.

The number 7 needs to be only somewhat over-represented in human discourse on randomness for the LLM to conclude, Random number = 7. But it has no idea what randomness is. In theory, a machine ought to find it easier than a human to generate random numbers since it doesn’t have our self-consciousness. But by the same token (ahem) it doesn’t have a model of the world. So it over-interprets the hints we have left in its training data - until all that remains is the simulation of a cliché.

When I was 7, coincidentally, my school teacher asked us all to guess a random number between 1 and 10. I randomly chose 7. So did he. I, and a handful of the other "lucky" kids, got to go out to break a little early. He did this several times throughout the year, and each time I remembered that his lucky number was 7, so I chose 7, and I got to go out to break a little early.

Since then my lucky number has been 7.

I think I learned this, in the same way my dog learned to sit when we gave her treats.

I posed the question of Claude who selected, as your predicted, 7. When challenged, Claude apologised, which was sweet.