Why did the 'terrible candidate' win?

Joe Biden's unlikely victory and what it tells us about how politics works

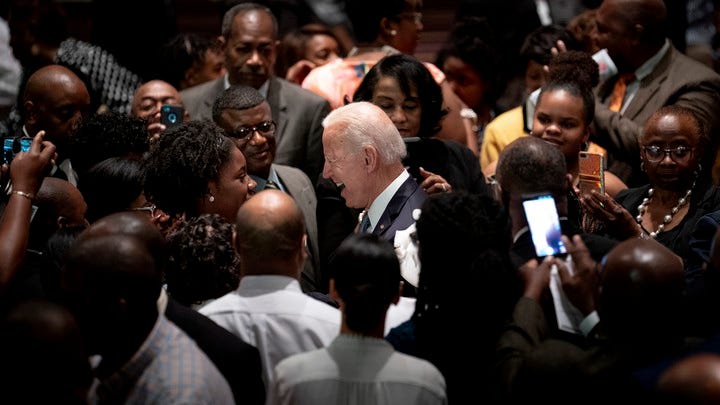

Joe Biden after his comeback victory in the South Carolina primary. (Elizabeth Frantz/Reuters)

This is a special edition of Ian Leslie’s newsletter, The Ruffian.

In the closing weeks of the campaign, Donald Trump mused out loud to his supporters on the near-impossibility of losing to - of all people - Joe Biden. “Man, it’s going to be embarrassing if I lose to this guy,” he would say at rallies. In private, according to the New York Times, he added an adjective: “Lose to this guy? This fucking guy?”

We can laugh at Trump’s disbelief now, but he was far from the only one. Way back in January 2019, Cas Mudde, an academic and Guardian columnist, declared that “Biden is the worst candidate for the Democrats and the best opponent for Trump”. Biden is old, Mudde informed readers, mentally unfit for the office, and not progressive enough.

A few months later, in the New York Times, the feminist author Jill Filipovich argued that if Democrats imagined that Biden was electable, they were mistaken. “Politics is not about appealing to the bland median. It’s about appealing to the people who actually feel motivated to turn out and vote.” In Britain, Owen Jones tweeted that making Biden the nominee would be an “utterly bewildering choice”.

It wasn’t just left-wing commentators predicting Biden’s failure. In late 2019, as the first primaries approached and Biden led the field in polls, the informed consensus was that his campaign was about to shatter on contact with voters. A profile in New York magazine was headlined “Joe Biden’s Zombie Campaign”. It came replete with quotes from the former Obama strategist David Axelrod to the effect that Biden was a loser waiting to happen: “There is this sense of hanging on. And perhaps he can. But that’s generally not the way the physics of these things work.” Democrat elites, panicked, looked around for candidates who might stop Bernie Sanders. Mike Bloomberg was ushered into the race.

When Biden lost the first two primaries, his campaign was immediately written off. In New York magazine, Jonathan Chait wrote that Biden was now “almost certain to fail”. Bernie Sanders was said to be the near-certain nominee. But South Carolina’s African-American voters had other ideas: they delivered Biden a thumping comeback victory. As other candidates melted away, Biden went on to win decisive victories over Sanders.

In the New Statesman, Gary Younge, who preferred Sanders, could only shake his head: “I confess that what drives black America’s political affections has always been a bit of a mystery to me”. Biden, he continued, was “a terrible candidate”, gaffe-prone and rambling. The left-wing writer Owen Jones agreed, describing Biden as a “self-evidently woeful embarrassment of a candidate.”

Biden had led the field for two years, save for a brief interlude in February. He polled consistently better than any other candidates in match-ups with Trump. He emerged victorious from an intensely competitive Democratic primary. But no matter how much he won, he was called a loser.

It is unfair of me to single out these commentators. I could have picked many others to make the same point. They are merely representative of an assumption widely held among the media and political classes – that Joe Biden was a weak candidate, his weakness temporarily disguised by name recognition and accidental victories. Even after November 4th, some have suggested that he merely got lucky against an unpopular president in the middle of a national crisis. But Hillary Clinton –hailed as a strong candidate, back then – lost to the same man, and Biden’s polling lead over Trump long preceded the coronavirus.

This guy – this fucking guy - delivered one of the biggest Democratic victories of modern times, and certainly the most important.

So how did he do it?

The Biden Effect

Trump could and should have won this election. Since World War II, only two presidents have lost re-election bids, until now. Trump is the third, along with Jimmy Carter and the first George Bush. Incumbency is a big advantage in itself. Moreover, presidents who are rated highly on economic management, as Trump was and continued to be post-pandemic, should be even more confident of re-election. Even given Trump’s personal unpopularity, it would be foolish to argue that the Democrats didn’t need a very strong candidate to vanquish him.

Those who wanted Trump gone may be disappointed that he wasn’t buried in a landslide, but America’s polarised electorate is making close contests the norm. Biden’s projected margin in the popular vote is over 4%, making his a decisive victory by contemporary standards. He won back the key Midwestern states that led to Hillary Clinton’s defeat while also flipping states that no Democrat has won since the 1990s.

Had the party picked a more “progressive” champion, Trump would almost certainly be set for a second term. To see why, let’s zoom in to the middle of America. Nebraska happens to be one of only two states which splits its electoral college vote (Maine is the other). Overall, the state is solidly Republican, and Donald Trump duly picked up four of its five votes. But the fifth, representing the district of Omaha, went to Biden. This was the first time a Democrat had won one of Nebraska’s electoral votes since 2008. As it turns out, Biden won the electoral college with room to spare but this was a significant win, since in close elections, one vote can make all the difference.

There was also an election for a House seat, in which the Democrat candidate was Kara Eastman, who comes from the party’s radical wing. Eastman was backed by progressive groups like Justice for Democrats, closely associated with Alexandra Ocasio-Cortez. Those groups poured money into the race on her behalf. Eastman lost to her Republican opponent by five points. Biden won by seven.

Progressives have had extraordinary success in recent years in becoming the public face of the Democrat party. But the bitter pill they must swallow is that Joe Biden won because he is so clearly not one of them. Biden ran ahead of Democratic congressional candidates across the country, including in the pivotal swing states which are won or lost on very thin margins, and Democrats in those states lost to Republicans. Biden won because he is more popular than his party. Given that America’s electoral college puts Democrat presidential candidates at a disadvantage, that was crucial. If voters had perceived Biden as a typical modern Democrat, Trump would have been re-elected.

Those voters in South Carolina who were so mysterious to Gary Younge had seen something he could not: that Joe Biden was the only Democrat capable of beating Trump.

Why was Biden underrated?

I think the reason Biden was so consistently underrated is this: “populists” have won so many victories in recent years that commentators have forgotten how politics works. Despite appearances, it doesn’t need to be a zero-sum war between diehard radicals from opposite sides. Most of the time, the candidate perceived as most moderate wins. This is not ideology so much as empirical fact; one of the most well established truths in political science.

It’s worth spending a bit of time on what it means to be moderate. It doesn’t mean identifying the middle of every policy debate and sticking your flag there. Biden’s policy platform is more radical than any Democratic nominee in modern history. His climate plan, developed with advisers from the progressive wing of the party, was hailed by Vox as “shockingly ambitious” (even if, given his party’s mediocre performance in Congress, he may not be able to implement much of it).

If Bernie Sanders or Elizabeth Warren were running on such a platform, it might be seen as dangerously radical, but since Biden’s political brand is indelibly moderate voters are inclined to see his policies the same way. As Andrew Yang, his former opponent in the primaries, put it, “The magic of Joe Biden is that everything he does becomes the new reasonable.” His victory is a lesson for centrists as much as progressives: get the politics right and there is no need to be timid on policy.

Why did voters see Biden as reasonable? Because he has always been close to or just to the right of his party’s centre of gravity and has made it his job to be there. Conversely, candidates from the right do best when they are perceived as being to the left of their party.

Many people drew the wrong lesson from Trump’s victory in 2016, including, perhaps, Trump himself. His wild, offensive rhetoric obscured the fact that he was perceived by voters to be the most moderate candidate in the contest. According to Gallup, voters regarded Trump as “the least conservative candidate in recent history.” Trump picked fights with the right wing of his party, taking on neo-conservatives over Iraq and free market ideologues over trade. That positioned him as moderate even given his hardline position on immigration. Only in office did voters start to think of Trump as extreme, after he allowed his own party to push him to the right, on healthcare in particular. That opened up more space for Biden to position himself as the moderate choice in 2020.

Another principle of moderate politics is that you should address voters who are not naturally inclined to vote for you, or your party. Biden won because he appealed directly to people who voted for Trump or an independent conservative candidate in 2016, while winning the most voters in history.

This principle should be obvious – why wouldn’t you want more voters? Yet it has become almost conventional wisdom that politics is now about mobilization of one’s own side. Since there are no voters whose minds can be changed, nobody should bother trying.

This is empirically wrong, of course: in tight elections, flipping only a small number of voters from one side to the other is even more important, since you are not only winning votes but depriving your opponent of them. But it is also antithetical to the democratic (small ‘d’) ethos – an ethos that Biden is soaked in.

In April, Biden and Sanders held an online conversation, to announce plans to collaborate on policy. It was a notably warm encounter. “I know you are the kind of guy who is going to be inclusive,” said Sanders. “You want to bring people in, even people who disagree with you.” I fondly imagine Sanders, thinking, even as he said it, Hey, maybe there’s something in that. He lost to Biden because he signally failed to win over voters and politicians who did not already agree with him, and showed not the slightest interest in doing so.

Erin Schaff/NYT

That bring us to the third principle of moderate politics, actually more of an attitude or sensibility, but which may be the most important of all. Successful moderates really like voters – all voters.

Voters generally liked Biden: 52% had a favourable view of him (in 2016, only 43% said the same of Clinton). This probably something to do with the fact that there are no “deplorables” in Biden’s universe. Every voter, to his mind, is a potential friend. That may not literally be true, but believing it is his political superpower. Covid restrictions aside, you get the impression he would kiss every baby and pump every hand - even if the baby, or the voter, was wearing a MAGA cap. As one of his advisers remarked, “I don’t know if it’s the Irish in him or what but he just really likes people.”

Biden’s pitch throughout the weeks leading up to election day included a call to rise above politics. Every speech and every ad included some variation on “we don’t have to agree”. Populists and radicals would never say this, because to them, politics is all. Biden believes that everyone in his country shares certain beliefs and that if he is the candidate who best represents those core beliefs, he will win. That meant he was able to skilfully navigate what would been a very tricky issue for other Democrats: the protests over George Floyd. Biden welcomed the protests, called for police reform, while loudly denouncing rioting and dismissing “defund”. He knew that’s where most voters were, left and right.

Biden likes and respects voters as people, which makes voters give him the benefit of the doubt. As Ezra Klein puts it, “the deeper question isn’t how much voters like a politician, but whether they believe a politician likes them.”

Good enough

Biden can feel like a politician from another age and that might just be why he won. He suffers from fewer of the maladies which afflict modern politicians. He has little time for social media. Instead of pumping out cute gifs and emojis as Hillary Clinton did, his campaign used Twitter sparingly and formally, with little pretence that Biden was doing the tweeting. He didn’t seek out fights or flashpoints with his opponent, which made him very hard for Trump to deal with. He ignored pundits who urged him to move on from his core message – that American needs a grown-up in the White House. He kept everything simple.

One way in which Biden is, suddenly, modern, is his inability to be anything but who he is. His tendency to make gaffes hurt his previous presidential bids, but this time, nobody cared. Why would they, when his opponent was one, unending gaffe? In fact, Biden’s gaffes have come to function as a signal of his authenticity. He is who he is, clumsy speaking and all. He did not go to an Ivy League university and has never been part of the hyper-educated set that that has become so influential in US politics. That means he doesn’t think about voters as abstract entities, as data to be gathered or targets to be manipulated, but as people; people who want to feel safe, liked, respected and loved.

A common criticism of Biden during the primaries was that his support was “shallow”. Nobody really wanted to voted for Biden, it was said. People voted for him because he was deemed to be electable, and that was it. Trump took up this theme, noting that his voters were more enthusiastic about him than Biden’s were about Biden (fact check: true!). Of course, it didn’t help him.

We’ve become so used to the idea that enthusiasm is crucial - because it leads to mobilization – we’ve forgotten that wide and shallow support beats narrow and deep every time. After all, no vote counts for more than any other vote (and turnout tends to be defined by more by the moment than the candidate).

We now deem a politician successful only if a whole sickly iconography is created around them; memes, gifs, tee-shirts, children’s books. But we don’t have to love our politicians. In fact, it’s dangerous to do so, since it either blinds us to their flaws or leads to disappointment and rancour. And if you really love your candidate, there’s a good chance someone else will really hate them. Voters like Biden just enough, and they think he will do a decent enough job, and that’s enough.

In fact, right now, that’s bloody wonderful.