How - and Why - To Read...

...in a World That's Giving Up On It

Catch-up service:

Best of The Ruffian 2024

The Enigma of Luigi Mangione

My Ten Favourite Books Of the Year

Literacy’s rise was fast and its fall may be even faster. People have been setting down squiggles on pages, and deciphering them, for five thousand years or so: a relatively brief span in human terms. Societies in which most people could read and write only arrived in the last 150-200 years. But now, having gone to the trouble of teaching ourselves this difficult skill, we seem to be concluding that it’s more trouble than it’s worth.

In a column for the Financial Times, Sarah O’Connor draws our attention to a new report from the OECD on global literacy and numeracy, based on a survey of 160,000 adults in 31 countries. Nearly all countries experienced declines in literary proficiency among adults without higher education. Among more educated adults, literary proficiency fell in 13 countries. Thirty per cent of Americans read at a level you would expect from a ten-year-old child, according to the survey’s director, who attributes the deterioration to social media.

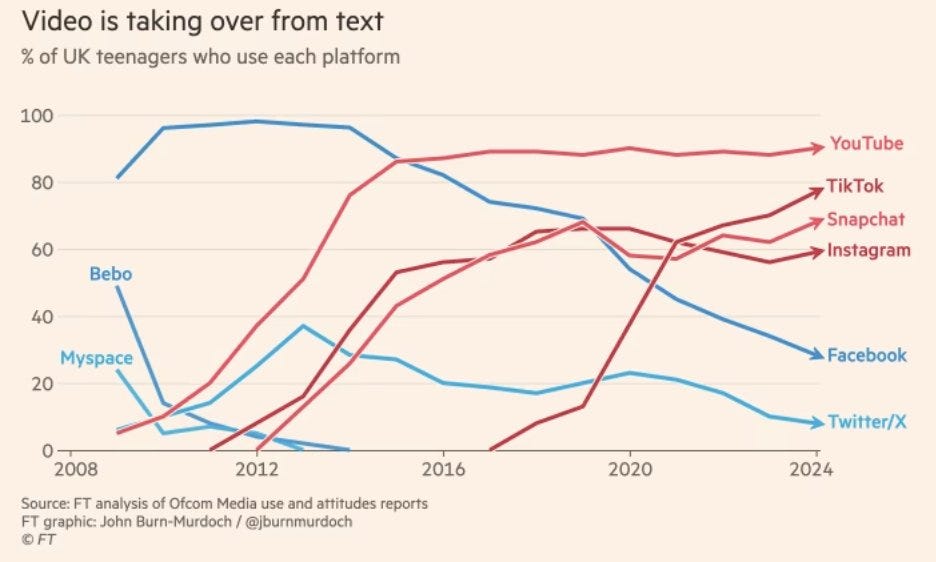

We probably blame too much on social media, but in this case it does seem a likely culprit, along with gaming and other digital activity. While it started off as text-based, social media is increasingly a realm of video and audio. We can expect the same direction of travel when it comes to AI; our text-based chatbots will soon just be voices and pictures, for most users.

What does it mean to call a society literate or post-literate? It refers not just to the skills of reading and writing, but to the centrality of the written word - to the extent to which it shapes our culture, politics, and leisure, and, most fundamentally, our minds. Neil Postman’s 1985 book Amusing Ourselves To Death, a brilliantly written polemic, argued that literacy was crucial to the rise of secular democracy. It raised the collective intelligence of society by making the citizenry better at thinking and arguing.

Literacy inculcates particular habits of thought and discourse that orality does not. Sentence by sentence, a written text makes it easier to see how one proposition follows from another - or fails to. It shows you the workings of an argument rather than just conveying its effect. (That’s why writing is such a powerful tool of thinking. I’ve often started with a thought - or the feeling of a thought - and realised, through the act of trying to make it make sense, that I actually believe something different).

Without this discipline, intuitions and feelings reign supreme. In a society where literacy is marginalised, the vibe is king. Public discourse devolves into the marijuana-smoke haze of a Joe Rogan podcast and the cocaine snort of a TikTok video. We become more easily gulled by specious claims and less patient with argument and complexity. Superficial explanations prevail, clichés go unchallenged. (Postman points out that in pre-literate societies, legal disputes are settled by sayings like “possession is nine tenths of the law”.) Politicians lose their ability to analyse policy in depth and become obsessed by how things look.

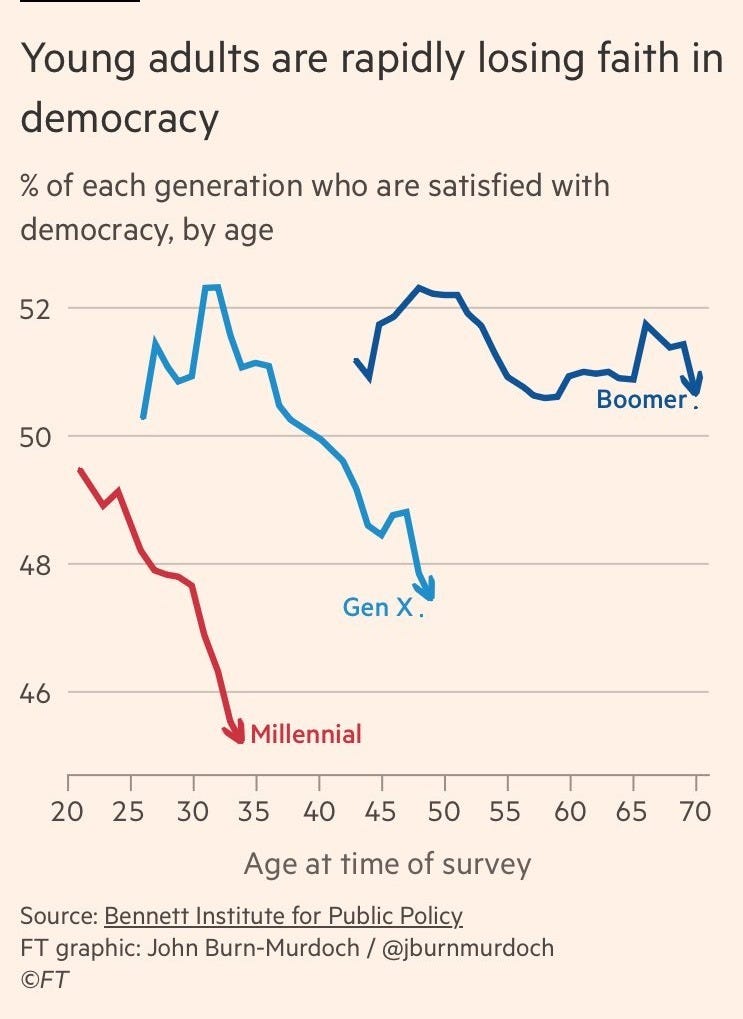

Literacy, which makes us stop and think, goes against the grain of human nature. The same is true of democracy itself, with its tiresome requirement to acknowledge the reality of other minds (a task that was facilitated by the novel).1 Postman believed television was destroying our minds. We can only imagine how appalled he would have been by social media. He certainly wouldn’t have been surprised to see that its heaviest users have the least faith in democracy:

But what of it? I’m pretty sure you agree with me that these trends are regrettable. You wouldn’t be here if you didn’t like and respect the written word. You’re probably what we might call a ‘deep reader’ - someone who regularly reads books and longer articles.2 You’re also, if I might make an impertinent guess, at least mildly contrarian. If society is giving up on reading, that only makes you want to read more.

I’m with you. There’s another question here, however. In brute economic terms, are we deep readers just stubborn, backward-looking losers? Or does being highly skilled at reading and writing become more valuable in a post-literate society? I can see a good case for the latter. After all, increasing scarcity often leads to higher prices.

“Cognitive endurance” is the ability to sustain effortful thinking over a continuous period of time. It’s a crucial skill. A new study in the Quarterly Journal of Economics points out that richer people tend to have it more than poorer people; it’s one of those self-reinforcing effects that make inequality so hard to fix. The researchers provide strong evidence that good schools don’t just teach specific academic skills but instil this all-purpose ability, by getting students to practice effortful thinking for long stretches.

Building cognitive endurance doesn’t cease to be important after you leave education. In our ADHD, chatbot-served world, those who work hard at cultivating it will be at an increasing advantage. Reading is one way to do so. When you’re reading a book, you aren’t just absorbing the contents of the book, you’re exercising those slow-twitch mental muscles that enable you to absorb complex information more generally. I suspect that when you give up on deep reading, this capacity atrophies fairly quickly.

You might have noticed that some of the people doing best in voice-based media are voracious readers. The Rest Is History is successful because its presenters have read and continue to read a remarkable number of books. Holland and Sandbrook share a vast capacity for effortful cognitive work, which enables them to make podcasting sound like effortless fun. Similarly, the most productive users of AI will be those who already have, and who cultivate, specialised knowledge and cognitive skills. It’s all about the prompt. The GIGO principle and its inverse (‘Genius In, Genius Out’?) have never been more pertinent.

In a society where people are reading less, you need to read more. But knowing you should read more and doing it are two different things.

How To Read More

Even among my deep-reading friends I increasingly hear it said, with a sense of passive resignation, “I just don’t read as much as I used to”. Our glittering devices have certainly improved our non-reading options. But if I’m right and reading is more important and more valuable than ever, then it’s surely worth putting extra effort into. Look, I won’t pretend to have cracked this problem. As I said in my post on my favourite books of 2024, I didn’t have a good reading year, and what follows is advice to me as much as it is to you. But here are three principles that, if adhered to, will make a big difference to your reading life.