How To Do Politics When Nobody Knows Anything

If You Want To Make God Laugh Tell Him Your Political Strategy

Catch-up service:

Podcast: James Marriott on Books of The Year

When The Mind Outlasts the Brain

How To Choose Your Nemesis

My Ten Favourite Books of the Year

How To Push Back With a Smile

From Community To Tribe

TikTok Can’t Take All the Blame For Populism

John & Paul is a book of the year in the Times, the New York Times, the Economist, the Financial Times, The Observer, the Daily Mail, the Daily Express, Prospect, Esquire, NPR, Kirkus. Conan O’Brien mentions it twice in this bonus Rest Is History bit. In short. there’s a pretty good chance that someone you love will love it. Links to UK and US retailers here.

One of the signature features of democratic politics is its capacity to surprise. On the eve of any given election it still thrills me to think nobody knows how this will turn out. In the British system nobody even knows who’ll be Prime Minister the next day. Despite lavishly funded micro-targeted campaigns, despite ever more sophisticated polling methodologies and prediction markets, voters still reserve the right to make everyone look foolish. That’s wonderful.

Modern polls are usually accurate within a few points, but those few points can make a big difference. Then there are the longer-range uncertainties: the way that a presidential candidate who breaks all the rules of presidential campaigning can win, and then lose, and then win again; the way an apparently sure thing for an upcoming election can see their popularity collapse because of another country’s election. The way that a politician closely associated with a national disaster can within a few years become its most likely next leader.

You can have too much surprise. Western democracies may be becoming too unpredictable to deliver the stability on which their legitimacy depends. Nowhere is this more true than in Britain, which, after a run of six prime ministers in nine years, is now contemplating the possibility of seven in ten. This isn’t just a series of unfortunate events; it’s a consequence, at least in part, of voters abandoning the two-party oligopoly around which our constitution is loosely arranged, and behaving as if we live in a multi-party system. The friction between electorate and system is generating a lot of randomness.1

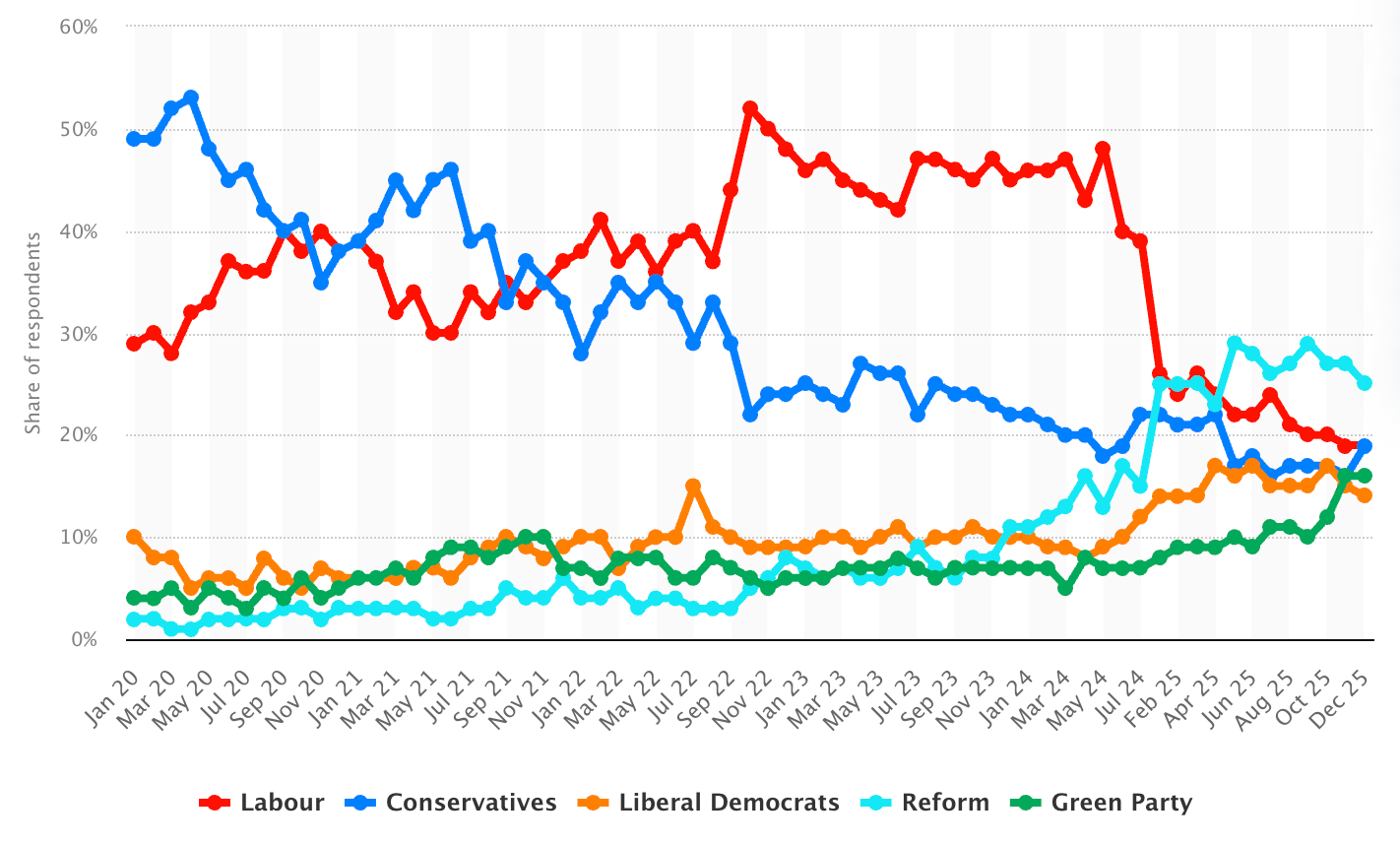

The next election is and will remain fiendishly hard to call. We have now entered an era that the brilliant political analyst James Kanagasooriam calls “peak chaos” for polling. He gives two reasons. First, the decline of the two main parties. At the last election Labour and the Conservatives had the lowest combined vote share for a hundred years, 57%; in the polls their combined share is now under 40%. Robust populist parties have emerged to left and right: the Greens and Reform. Throw in the stubbornly resilient Liberal Democrats and you have a five-party face-off. (This is before we get to the Scots and Welsh nationalists). The gap between first and fifth parties has never been this small.

Football fans know that the Premier League table has been unusually bunched together this season, with just a few points separating the upper from the lower reaches. Our political situation is not dissimilar. In this situation, many seats will be won by one of those five with an historically tiny vote share of about 20%.

The second source of polling chaos is tactical voting. People are increasingly willing to vote promiscuously and tactically. They will vote for a second or third preference in order to keep another party out. They will vote across “liberal” and “conservative” blocs, voting Reform in seats where the Tories have no chance, and vice versa. They will even between blocs; it’s very hard to predict, for instance, who a Lib Dem voter will pick once they decide to use their vote for another party. Pollsters don’t yet know how to model this behaviour.

Fragmentation has been accompanied by acceleration. Most Prime Ministers have post-election honeymoons before slowly losing altitude. Keir Starmer has had a nosedive almost violent in its extent and speed. He went from a net rating of zero shortly after the election (44% favourable, 44% unfavourable) to minus 66% just over a year later (13% vs 79%). (These are single polls but reflective of the general trend). After winning a big election victory in 2024 he is now the most unpopular PM in nearly half a century. At the same time, Reform’s vote share has ballooned. Whether it will collapse equally fast is hard to say.

That’s Britain, but other countries are experiencing chaos in different forms. There are at least two macro reasons for all this increased uncertainty. One is geopolitical. The world’s most powerful democracy is acting like a nasty drunk, roiling the world economy on a whim, carelessly smashing settled alliances. The second is the disruption caused by new technologies, most obviously in the sphere of media and communication, but more fundamentally in the structure of our economies. The future of everything is harder to call than ever, including and especially politics.

Most of today’s senior politicians and commentators came of age under a system in which the rules of the game hadn’t changed much for decades. In Britain, you could pretty much guarantee that the next PM would be from one of two parties. You could be sure that most people got their information from TV and newspapers. There was a lot of agreement on which kinds of political behaviour were rewarded by voters and which punished.

The intuitions of the generation in charge were formed in this lost world. In evolutionary biology the “mismatch theory” says that advantageous traits can become maladaptive when the environment changes; the human preference for sugar and fat was useful when food was scarce but dangerous when crisps and chocolate are always within an arm’s reach. Many of today’s politicians look hopelessly mismatched to the moment, including and especially the ones in power.

How should ambitious politicians behave in this new era? The answer should obviously be different to whatever it was in the old era. Even from the perspective of an observer rather than a participant, I’ve come to realise that much what I thought I knew about politics is close to worthless. I am going to answer my question, however, out of pure hubris. So here are six principles for political success in an era of radical uncertainty. (And after that, a very juicy Rattle Bag).