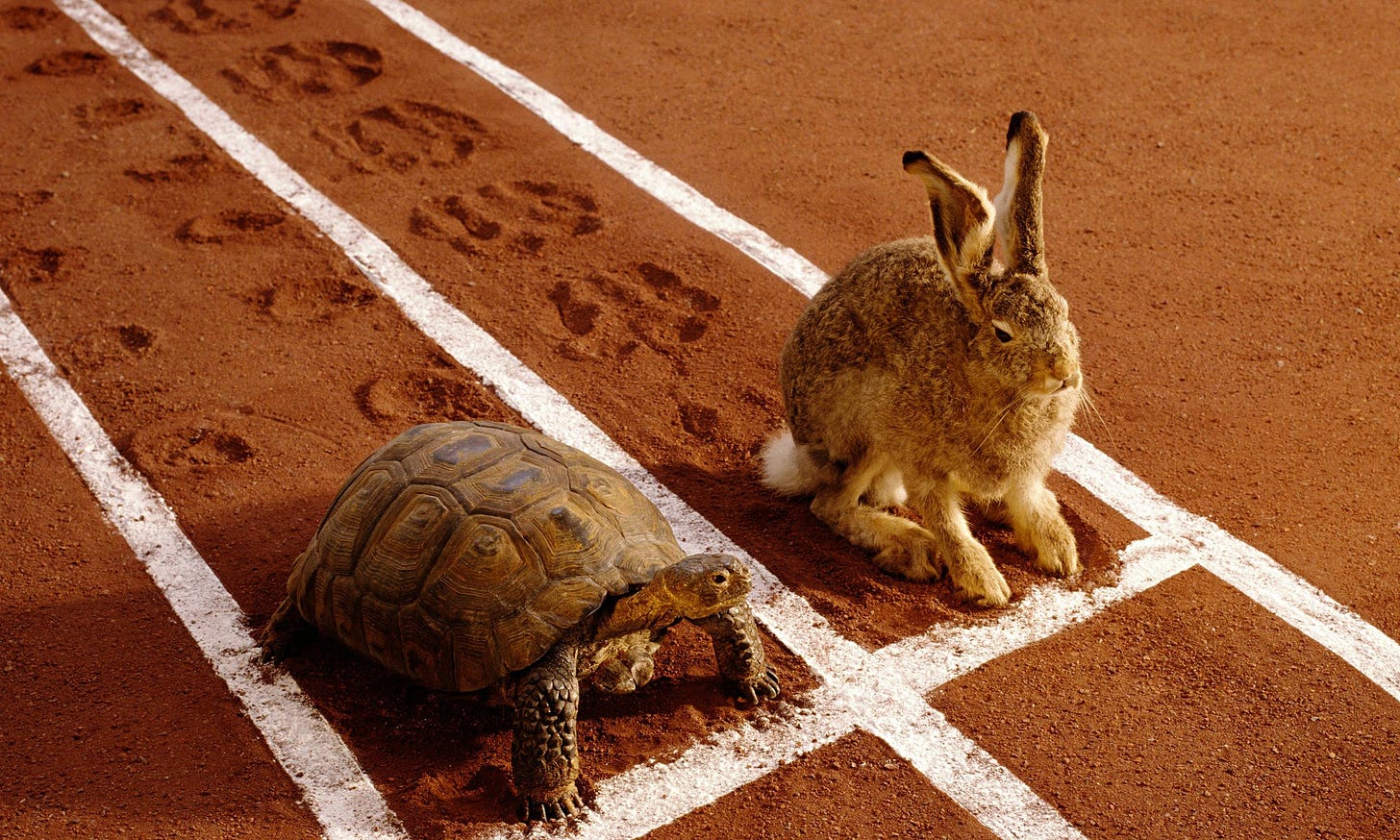

In Praise of Slow Learners

How the Tortoise Beats the Hare

Catch-up service:

The State of the Culture Is…Not Bad

Google Gemini & Office Politics

How To Fix DEI

In his book on the practice of writing novels, Haruki Murakami tells a story about two men, one of them very clever, the other less so, who travel to Mount Fuji to see what all the fuss is about. They stand at the bottom, gazing up. The clever one moves nimbly around to different vantage points, scanning the mountain intently, processing information on terrain and aspect. “Now I see what makes it so special,” he says, and heads home, satisfied.

The less clever one can’t figure it out like that. So he stays behind, and climbs the mountain. It takes him many hours and much effort. By the time he gets to the summit, he’s utterly exhausted. But now he understands Mount Fuji in a way his friend does not.

Murakami says that novelists tend to be like the stupider of the two men. They are inefficient learners. They can’t figure things out quickly or easily, or at least they don’t feel like they can. They don’t have a great facility for abstract thought. They rely on the concrete and the sensual to figure the world out. They climb the mountain, one detail at a time. He writes: “The way I see it, people with brilliant minds are not particularly well suited to writing novels…the writing of a novel, or the telling of a story, is an activity that takes place at a slow pace - in low gear, so speak.”

Like a lot of people, I would prefer to be smarter than I am. Unlike some, it’s not something I worry about much. I worried about it more when I was younger, but now I’ve come to accept, on the basis of overwhelming evidence, that there are people - really quite a lot of people, including friends, colleagues, my wife - who are indisputably more intelligent than me, and that’s just the way it is. These people can absorb and retain information more successfully than me; learn the rules of a new game or language much faster than I can; are more agile of mind and fluent in speech.

I’ve also come, perhaps conveniently, to see that there are certain advantages to being a relatively slow learner. Now, I’m not going to argue that these advantages outweigh the disadvantages; given the opportunity to upgrade, I’d order a faster and more powerful brain. But I will suggest that we overrate fast learning and underrate slow learning, because we tend to treat all cognitive tasks like a sprint in which it makes sense to run as fast as possible from the start. Many tasks in life are more like long distance runs, where it pays to go slowly in order to minimise your race time. Novel-writing is one (Murakami is himself a dedicated marathon runner).

Slow learners have a hidden advantage over fast learners: they have to learn adaptive strategies in order to keep up with their smarter peers, and these strategies can prove very valuable in the longer run - so valuable that sometimes slow learners overtake their peers.

Kip Thorne is a co-winner of the 2017 Nobel Prize for work on gravitational physics. You would imagine someone like that has always felt like the smartest person in the room. But when Thorne first arrived at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech), in the 1950s, he struggled: “The first year was very hard; my mind didn’t work as quickly as other students’” he said. “I realized that to survive, I had to develop strategies to compensate.”

In the interview I’m citing, he doesn’t specify what those strategies are, but we can guess. Perhaps he worked harder than the others and thought deeper, dwelling on problems that his classmates would have found solutions to quickly, sticking with them doggedly until he understood them from the ground up. Perhaps he also thought laterally about them, in ways the other students wouldn’t even have considered, or perhaps he brought to bear learning from adjacent fields of knowledge. However he did it, Thorne had to climb the mountain by his own route, and in doing so, he exceeded the achievements of his faster-learning classmates.

Of course, such strategies are a form of intelligence, too. In his essay on the nature of understanding, the technologist and writer Nabeel Qureshi distinguishes between the ‘hardware’ and ‘software’ of intelligence. What fast learners have is superior hardware - raw processing power, large memory capacity. But slow learners can sometimes outflank fast learners, intellectually, if they have superior software: character traits like honesty, bravery, and humility, and behaviour traits like curiosity and persistence.

The good thing about these traits - it might better to think of them as habits - is that they are elastic. Even if there is a genetic component to them, they can be learned, practiced, developed. Note that this is an argument for putting yourself in rooms with people who are faster learners than you. When you come up against people with better hardware you’re strongly incentivised to develop your software, in order to match or better your peers and competitors.

If there are traits that can make dimmer people smarter, the converse is also true. One of the pitfalls faced by fast learners is that they are not incentivised to develop their software. Really clever people get a lot of feedback early on in life that they are, well, really clever. As they get older, they discount information that suggests they haven’t understood something and over-weight information that suggests they have. Consequently, they can become gradually stupid.

Charlie Munger: “A lot of smart people think they’re way smarter than they are, and therefore they do worse than dumb people. And it’s very common to be utterly brilliant and think you’re way the hell smarter than you are." (I wrote about this effect in 2022 after Liz Truss and Kwasi Kwarteng crashed the British economy. Politics rewards fast learners right up until those fast learners fail spectacularly.) Slow learners are less likely to fall prey to this trap, since they’re more used to getting and noticing feedback which tells them they’re not so smart.

Nabeel Qureshi is particularly interested in the “will to understand” - the dogged refusal to accept superficial answers, the desire to go further and deeper in the search for truth. That is a slow learning trait - it literally slows you down - and much about the education system and professional world militates against it. You can mechanically perform calculus operations without ever deeply understanding calculus, and in fact that’s what you’re encouraged to do at school, since nobody has time for your questions; just do what you need to pass the exam. At work, once you learn the tricks of making an impressive presentation, you stop pushing yourself to really understand what you’re presenting. There’s no time.

Speed kills understanding. The secret of improving your intelligence, and your judgement, is knowing when to choose the slow route; when to look at the primary data yourself rather than accept a second or fifth-hand summary of it; when to take three months to read one great book rather than trying to read twenty mediocre ones; when to admit that you haven’t grasped a problem, rather than generating a plausible but superficial take on it; when to ask the stupid question that everyone’s wondering about but nobody wants to verbalise; when to push those around you or just yourself to more precisely define what you’re arguing about.

Slow learners are more likely to do things the hard way, because they haven’t been pampered by their own brain. They’re very familiar with the feeling of not-understanding, and have learned to welcome it as a spur.

In short, those of us who are slow learners needn’t be embarrassed about it. We may not understand things as quickly as some, but the habit of conscious not-understanding is a valuable one to have. It can be very productive to dwell, even revel, in incomprehension.

Somebody who understands this is James H. Simons. Simons received his doctorate in mathematics at 23 and taught the subject at Harvard and Princeton, while working as a code breaker for the US National Security Agency. Later he won geometry’s highest prize, before founding Renaissance Technologies, one of the world’s most successful hedge funds. Now he focuses on his philanthropic efforts, which include training and funding maths teachers.

In a New York Times profile of him from 2014, when he was 76, what shines through is the profound delight and solace Simons takes in thinking - in thinking long, hard, and slow. “I wasn’t the fastest guy in the world,” he says, looking back on his youth. “I wouldn’t have done well in an Olympiad or a math contest. But I like to ponder. And pondering things, just sort of thinking about it and thinking about it, turns out to be a pretty good approach.”

This is Part I. In Part II, after the jump, I look the virtues of slow learning in the context of teams and organisations, personal relationships, and AI.