Nike's Winning Strategy

On the Cultural Significance of Its 2024 Olympics Campaign

Catch-up service:

Joe Biden Is Not a Hero

The Trump Shooting Was Fake News

Five Bad Motivations With Good Outcomes

Do You Wear the Mask Or Does the Mask Wear You?

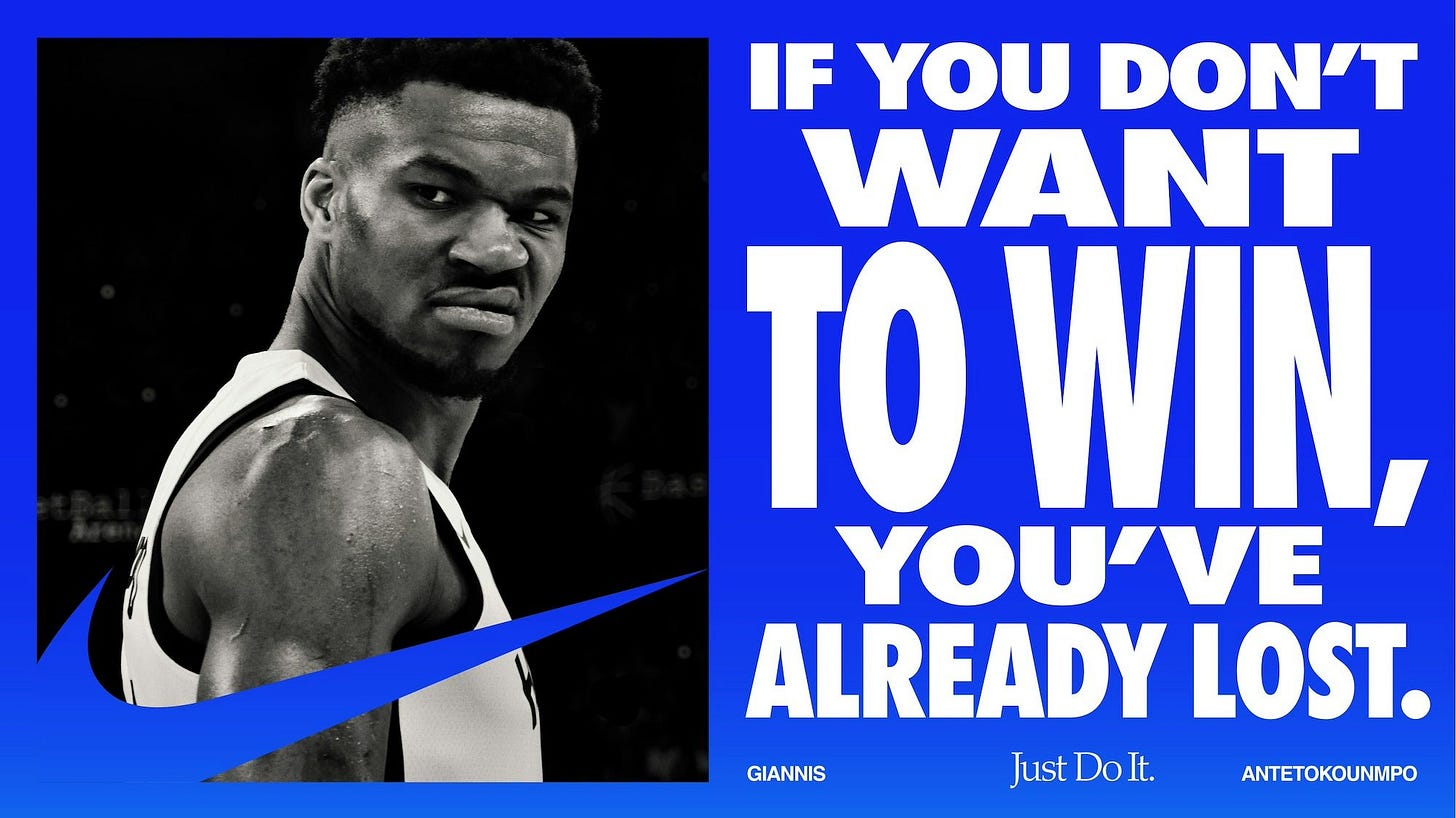

I can’t remember the last time I saw a Nike ad I was even interested by, let alone one I like. (To be clear, I speak as a consumer of advertising - and former maker of it - rather than of sportswear.) But the brand’s new campaign, created to coincide with the Paris Olympics, is striking. It has a real idea at the heart of it and I think it taps into the cultural zeitgeist. Take a look at the TV ad:

If you can’t view it right now, I’ll summarise. Over pictures of Nike-sponsored athletes being super-good at sport while also looking super-mean, and a Beethoven-Ninth-ish soundtrack, a gravelly male voice says:

”Am I a bad person? Tell me, am I?"

Over the course of the ad, he returns to this question, baiting and goading the viewer with it, while describing his character; that is, the character of an elite sportsperson:

“I’m single-minded, I’m deceptive, I’m obsessive, I’m selfish…I have no empathy. I don’t respect you! I’m never satisfied. I have an obsession with power.

I’m irrational. I have zero remorse. I have no sense of compassion! I’m delusional. I’m maniacal…I think I’m better than everyone else. I want to take what’s yours and never give it back. What’s mine is mine and what’s yours is mine.

Does that make me a bad person? Tell me, does it?”

As the music reaches it climax and we see athletes celebrating victory, the on-screen slogan reads “WINNING ISN’T FOR EVERYONE”.

Let me note a few things about this ad, as an ad, before I go all Roland Barthes and discuss its cultural resonance.

First, it feels like classic Nike; the kind of thing which made the brand one of the best, perhaps the best, advertiser in the world back in the 1990s and 2000s. It is bold, mischievous, there’s an edge to it. The script is first-rate, magnificently performed by Willem Dafoe. It poses a meaty question - can you be a nice person and a champion?

Having said that, when I say it feels like classic Nike, that’s exactly what I mean. It is like a pastiche of Nike ads past, rather than the thing itself. The format is familiar. As a film it’s perilously close to a mood tape (it’s the Olympics, guys: couldn’t you find money for a shoot?). But putting my gripes aside, let’s take a closer look at the thinking behind it.

Nike’s business is in bad shape. Its stock price is down two thirds from its peak in 2021. Why? Because it took its own brand for granted. At the start of 2020 a new CEO took over (Phil Knight, Nike’s founder, retired in 2015). John Donahue’s background wasn’t in sports marketing or retail, but e-commerce and IT. He likes numbers, not vibes. When Covid hit and high streets shut down, he saw an opportunity to take Nike out of retailers like Macy’s and Footlocker and sell direct to consumers, online, at higher margins. He also cut marketing spend. Nike shoes sell themselves, right?

This seemed like a good idea until it wasn’t. After ramping up at first, Nike’s sales growth has slowed almost to a standstill. Its absence from the shelves and from media has given established competitors like New Balance, and newer brands like the Swiss company On, the opportunity to win over consumers - those disloyal and capricious creatures - at Nike’s expense. Donahue is now scrambling backwards, rehiring old retail hands and spending more on ads, while trying to rediscover what made the brand special in the first place: its innovation and its attitude - the kind of thing that doesn’t show up on a spreadsheet.1

The new campaign should be seen in that context. It is an attempt to rekindle the energy which powered the Nike brand during its rise to world domination. In those days the brand was about reverence for elite athletes: for great men and women. Note: great, not good. Michael Jordan was ruthless, arrogant, and mean. He was a winner, above all. Add a dose of rebellion, and that was Nike. An ad for the 1996 Olympics declared, “You don’t win silver. You lose gold.”

Then the cultural weather changed.

The twenty-first century saw a vibe shift: more emphasis on equality and inclusion and empathy, and a growing antipathy towards the celebration of elitism of any kind. In the early 2010s it’s probably fair to say that the most influential marketer in America was Obama. His brand was diverse and egalitarian and democratic: yes we can. Celebrating an ubermensch class of athletes suddenly felt anachronistic.

In 2012, to coincide with the London Olympics, Nike launched a campaign called ‘Find Your Greatness’. It focused, not on elite sport, but on ordinary people engaged in some kind of sporting activity. This was a kinder, gentler Nike. The most well-known execution was this one:

Whereas in the 1990s, the brand at least pretended to target only athletes, ‘Find Your Greatness’ explicitly addressed non-athletes (though it claimed there is no such thing: its internal mission statement became, “If you have a body, you are an athlete”). Instead of gazing up at the stars, Nike invited consumers to look within. This approach seemed to work. Revenues grew strongly throughout most of the 2010s, stumbling towards the end of the decade, before taking off again in 2021 after the short-lived success of Donahue’s strategy.

Now, Nike has gone back to the future. The 2024 campaign is a throwback to twentieth century Nike. It’s about what makes the most successful athletes different to the rest of us, not what we have in common. It’s not about taking part, it’s about winning - and winning isn’t for everyone. So much for inclusion.

Why has Nike adopted this hardcore, old-school approach now, at this moment in its story, and at this moment in history? I can see three reasons.