Notes on The Greatest Night In Pop

A Study In Leadership, Teamwork, and Love

Catch-up service:

Rationalist Cults of Silicon Valley

The Data Says We’re Doing Fine So Why Are We Furious?

How Humans Got Language

The Diderot Effect

27 Notes on Growing Old(er)

Donald Trump and the End of Power

The Netflix documentary, The Greatest Night In Pop, tells the story of the making of We Are The World, the 1985 charity single featuring (almost) everyone in American pop at the time: Michael Jackson, Lionel Richie, Stevie Wonder, Bruce Springsteen, Bob Dylan, Diana Ross, Cyndi Lauper, Tina Turner, Billy Joel, Dionne Warwick…the list goes on and on.

The documentary is based on hours of footage from the night they recorded the single, only a few minutes of which was used for the original music video. The Greatest Night In Pop (TGNIP) came out eighteen months ago, and while millions of people have viewed it, I’m constantly surprised to learn that many have not. Everyone should.

If I had to recommend a documentary or just ‘something to watch on TV’ for absolutely anyone - man or woman, old or young, liberal or conservative, highbrow or lowbrow - I’d recommend The Greatest Night In Pop. It may not be the deepest, most profound ninety minutes of TV, but it is irresistibly enjoyable. And actually, like the best pop, it is deep; it just doesn’t pretend to be.

To us Brits, We Are The World was a mere footnote to Do They Know It’s Christmas? That record was instigated by Bob Geldof and Midge Ure and recorded by a supergroup of British and Irish musicians under the name Band Aid (an underrated pun). The proceeds went to famine victims in Ethiopia. We Are The World was made for the same cause.

I knew that, but what I learnt from TGNIP is that there was an element of racial pride in the American response, which arose spontaneously from a conversation between Harry Belafonte and Lionel Richie’s manager. Belafonte said, “We have white folks saving Black folks—we don’t have Black folks saving Black folks”. Lionel agreed, and the wheels started to turn.

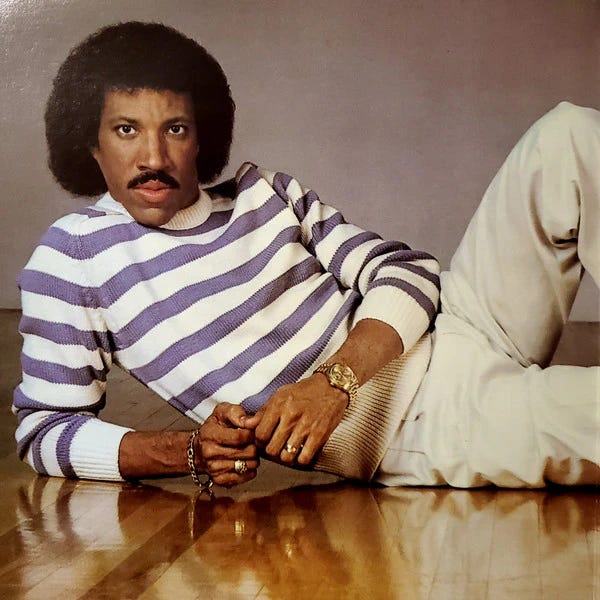

Ah, Lionel. The man who makes everything happen. It is perhaps not coincidental that he should emerge as the star of this documentary, given that he co-produced it. The same might be said of Paul McCartney, who emerged as the hero of Get Back. But in neither case do I sense corruption of historical truth. Richie is extraordinary, both as a talking head and in his 1985 incarnation. As chief interviewee - host might be a better word - he sparkles: mischievous, funny, a supreme storyteller. As the prime mover behind the recording of We Are The World, he is simply awesome.

After Belafonte’s prompt, Lionel calls Quincy Jones - the maestro, the master, the producer of the best-selling album of all time. Jones immediately says yes, and they call Michael Jackson and Stevie Wonder. Both agree, Stevie only belatedly because nobody can get hold of him (a theme of the doc is that Stevie Wonder is both delightful and utterly ungovernable). With these stars on board, they know that pretty much everyone else will want to be involved, and so it proves. They decide to recruit white stars as well as black, and get Springsteen and Joel and Kenny Rogers and Willie Nelson and others.

The first thing the principals need to do is come up with a song. Lionel goes to Michael’s house, and the pair spend several days hacking away at the piano (Stevie was invited but is AWOL). With a couple of days to go, they crack it (that is, Quincy likes it). The song is, well, fine: not a work of genius but a pleasant, gospel-inflected anthem, easy enough to sing without much preparation, catchy enough to be a hit. It does the job.

When he took up this baton, Richie was on a career high. He’d left The Commodores and broken out as a solo star. He was about to host the American Music Awards in Los Angeles, the biggest primetime music show, for which he himself was nominated for eight awards (he won six). It soon becomes apparent to all concerned that the best and perhaps only way to get all the talent in the same place to record a single would be to do it on the night of the awards, when so many of them are in town anyway. That would mean doing an all-night session, and for Lionel, it would mean first hosting a live awards show watched by millions - demanding, stressful, exhausting - then helping to run this second, private show right afterwards. No problem!

So it is that after the AMAs we see limousines dropping stars off at an LA recording studio. From a narrative point of view, a delicious premise emerges: a bunch of very famous, egotistical, impatient, nervous pop stars, most of whom don’t know each other (“It was like the first day of kindergarten”, recalls Richie) are brought together in a room to make a record of a song they barely know (they’ve heard a demo). It absolutely has to be a huge hit. They have about eight hours; there’s no coming back tomorrow.

It could have gone badly wrong. That it didn’t is testament to all involved but to Richie and Jones in particular. The two of them corral this unwieldy gaggle into making a sleek and successful product.1 The first time I watched TGNIP I enjoyed it unreflectively. When I watched it for a second time, I began to see it as a study in leadership, collaboration and teamwork.

I’ve written before about how diversity needs to be interpreted beyond demographic attributes like race and gender to temperament and personality. The British management researcher Meredith Belbin constructed a famous inventory of behavioural types which together make up a successful team: the Resource Investigator, the Coordinator, the Shaper, the Catalyst, and so on.

TGNIP prompted me to come up with an inventory of my own: the Decider, the Connector, the Conscience, the Old Buck, the Disrupter, the Weirdo, and the Lover.

THE DECIDER

Quincy Jones taped up a handwritten sign at the entrance to the studio: LEAVE YOUR EGO AT THE DOOR. He was possibly the only person in America who would have dared to write such a sign for such a crowd and certainly the only one who would have been listened to.

To lead a team of 40 superstars was a tough task but it certainly helped to be Quincy Jones. Aged 51, he been an arranger for Duke Ellington and Frank Sinatra; produced Donna Summer and Aretha Franklin; won multiple Grammys; turned Michael Jackson into the biggest artist in the world.

In TGNIP he is somewhat marginal to the action just because he is in the control room, while the camera roves the studio floor. We hear his voice over the intercom and see him when he comes onto the floor to coach someone through a difficult vocal part. (He wasn’t interviewed for the doc but we hear him speaking about the night from an earlier interview).

There’s no question he is in charge, though. His interventions are economical and precise; he doesn’t waste words. He is stern when he needs be, jocular in a restrained way; cool. Everyone in the room looks up to him, literally and metaphorically. He is friendly but not your best friend. He is here to make sure the job gets done, and done well. He is The Decider.

THE CONNECTOR

By contrast, Lionel Richie is very much your best friend. He is everywhere, talking to everyone: greeting, thanking, hugging; answering a thousand queries; soothing egos; telling stories and making jokes; giving pep talks; smoothing over potential conflicts; solving musical problems; hyping and cheerleading; raising the energy level when it flags; consoling the weary. Somebody else says of him, “He’s making the water flow.” That’s it.

Richie has a special knack for wrangling very talented, slightly nuts individuals. Cyndi Lauper, who was a massive star at that time, bigger than Madonna, decided on the evening of the recording that she wasn’t going to do it after all. The reason she gave is that her boyfriend didn’t like the demo of the song that Richie and Jackson had made. He’d told her it would never be a hit.

Lionel has to take a minute backstage at the awards ceremony which he is presenting to find Lauper, put any hurt feelings he might have aside, and cajole her into returning to the team. Later on, he’s the one negotiating with Prince over his possible participation over the phone. He also has to hide wine bottles from Al Jarreau so that he doesn’t get too drunk before recording his solo part. Details.

Richie recalls a moment of insight he had early in the evening, which leaders who have been in similarly fast-moving chaotic situations will no doubt recognise: “You realise you have no control. You're just...floating.”

During the session Richie bounces between the control room and the floor, passing on messages. having dropped a little sugar on them. He helps to shape every major decision. He is shrewd about what the stars need from him - confidence, a sense that there is a plan, even when there isn’t. He is intensely aware that once a group of artists start to debate some fine point the conversation will go on forever, and they don’t have forever. He says that the one answer he avoided was, “I'm not sure, what do you think?'"

The arrangement of the vocal parts is a musical and political minefield; Richie is there helping Jones work out who should do what and when. Then when the stars at the microphone - and even for these stars, it’s terrifying to sing lines you don’t know very well in front of your peers and rivals - he’s there for them, offering encouragement and suggestions. If Jones is a distant father, Richie is your closest sibling. The Decider relies on the Connector.

THE CONSCIENCE

Amidst these glittering American stars, in awards-ready designer gowns, coiffured hair and shining teeth, it is something of a shock to see Bob Geldof. He comes into the studio like a ghost, dishevelled, scrawny and pale. At Quincy Jones’s request, he addresses the group before the session begins.

These days perhaps we take what Geldof did and who he is for granted. He’s become, in the popular mind, a caricature, shouting at the camera. His brief appearance on TGNIP reminds us that he was (and probably still is) a natural orator of tremendous skill and force.

He doesn’t harangue or grandstand the assembled megastars and neither does he attempt to ingratiate himself with them. He speaks softly but directly and nervelessly. With barely any preliminaries, he lays it out: “'The price of a life this year is a piece of plastic seven inches wide with a hole in the middle.” He describes, briefly but vividly, the illness, poverty and despair he witnessed in Ethiopia. “I don't want to bring anyone down but maybe it's the best way of bringing out why you're here and what you're singing about."

And that’s it. Geldof speaks for about two minutes and steps back, having transformed the atmosphere in the room from febrile and slightly frivolous to seriousness and focus on the task at hand. It’s a credit to him and also to Jones, who knew exactly what the moment demanded. The Conscience has spoken, the party is over, now the work can begin.

THE OLD BUCK

One of the reasons that session works out is that despite there being so many artists and despite all the hierarchical tensions inherent to such a status-conscious world, there is a core group who have worked together for years and know each other extremely well. Richie, Jackson, Wonder, Diana Ross and Smokey Robinson all went to school, almost literally, at Motown. Of this number, Robinson is the most senior, even if the others are now bigger stars. He was both an artist and an executive at Motown.

In TGIP terms Robinson is like the guy in any office who has been there forever, a deep store of institutional knowledge. He has seen his protegés overtake him and admires what they have achieved, but likes to rib them now and again. He certainly isn’t intimidated by them in the way that outsiders and newcomers are, and, without overplaying his hand, he sometimes uses that advantage to tell them the truth.

There’s a moment when the session gets stuck because Wonder proposes that they sing a verse in Swahili. Jackson has a similar idea too. They want to make the song more ‘authentic’, more African, somehow, but of course, they have little knowledge of Africa and none of Ethiopia. Somebody points out Ethiopians don’t speak Swahili.

But because people are so nervous about disagreeing with Wonder and Jackson, this debate goes on and on in a painfully polite way for ages while everyone else gets bored and frustrated (Waylon Jennings walks out). Even Jones won’t put an end to it. It takes Robinson to sort it out. He eventually tells Michael and Stevie to stop with this African thing because it’s ridiculous, and that’s the end of that.

In Smokey’s interview, he talks about how he’d known Michael and Stevie since they were kids. And of course, he knew them at a workplace that was all about getting shit done; that didn’t venerate its stars; that didn’t have time for egos. “At Motown, that’s how we did each other,” he says, and the Old Buck has a smile on his face.

THE DISRUPTER

In many teams, particularly in the creative industries, there is someone who is only tangentially attached to reality - at least, to the mundane reality of schedules, deadlines, and rules. In TGNIP, Stevie Wonder comes across as the epitome of a wayward, contrarian, incorrigibly non-compliant co-worker who moves to his own beat. Quite often, these individuals don’t actually have the talent to justify being a free spirit, but sometimes they are indisputably brilliant, and capable of lifting everyone’s game.

Wonder is obviously in the latter category, and he also comes across as a likeable kind of maverick rather than the asshole variety. You can see that he annoys the hell out of Richie and Jones at points (though Richie would never show it) but also that he is loved by all. When everyone is on edge it’s very apparent that he's completely oblivious to any tension which loosens everyone up. He makes people laugh and shake their heads. This Disrupter is an inspiration.

THE WEIRDO

The best subplot in TGNIP is the redemption of Bob Dylan. Early on in the session, Quincy has the whole group sing the chorus together, and as the camera pans across the strenuously vocalising stars we see Bob moving his mouth a little but barely singing at all, like he doesn’t know the song and also like he’s having an existential crisis.

At first, you imagine he’s thinking, why the hell am I here with these idiots singing this terrible song, I’m Bob Dylan. But then you realise he’s just feeling nervous and out of place. He wasn’t a smooth, vocally athletic singer like many of the artists in the room, and if the careers of Richie and Jackson and others in the room were peaking, his was at or near its nadir. He is also - and this is something that really only struck me during TGNIP - what today we’d call neurodivergent; a socially awkward guy operating on a different wavelength to everyone else. He’s not arrogant; he’s different.

In every company there’s at least one weirdo who doesn’t quite fit in. Trying to make the fit in is a mistake; the aim is to make the most of their weirdness, while making everyone, including them, feel at ease with it.

Towards the end of the session, deep into the morning, Bob is called on to record some ad libs over the final chorus - “We are the ones who make a better world, so let’s start giving”. Standing by the mic, clinging to a piece of sheet music, he looks lost and nervous. He can’t get it right, he barely knows where to start. Lionel is there to help him - of course - and so is Stevie Wonder. They tell him he’s doing great. Dylan demurs.

Then comes a glorious moment. Bob shyly asks Stevie to play it through for him at the piano. And Stevie, who is a great vocal mimic, sits down with Bob and Lionel around him and starts belting out the chorus in the style of Bob Dylan. When Bob returns to the mic, it’s with a huge grin on his face. “Must be in a dream or something,” he says. And then he nails it

Lionel whoops, Quincy comes over and gives Bob a big hug. “That was fantastic,” says Quincy. “If you say so,” says Bob.

THE LOVER

One of the sweetest moments in the film is one we don’t see but hear about, from Tom Bahler, the vocal arranger hired by Jones. He recalls seeing Diana Ross nervously approach Daryl Hall. Holding the sheet music for the song that had been distributed to everyone, she says, “Daryl, I’m your biggest fan. Would you sign this for me?” He agrees, and this little exchange somehow gives permission to everyone else to do the same. Famous and garlanded singers start approaching the singers they admire to ask for an autograph.

The initial exchange is particularly touching to hear about because it’s Diana Ross - a pop legend and a legendary diva. And she’s approaching Daryl Hall. I mean, he’s great, and no doubt was selling more records than she was at the time, but still. It shows that inside every pop star, there is a fan; a lover of music and fellow musicians. And Ross had the bravery and humility to follow Quincy Jones’s handwritten instruction, and let that fan speak.

Ultimately, The Greatest Night In Pop is moving as well as fun, because by the end of it you sense that this group of frazzled and adrenalised stars have escaped their high-powered, high-pressure public selves and rediscovered a pure love for the struggle and joy of making a record with people who are really good at it - for making a better world by making a better song. They all have ambition, but tonight they have recalled their purpose.

The session is coming to a close. Most of the artists have said goodbye to each other and are on their way home, or to wherever they are headed next, as the sun comes up in Los Angeles. Diana Ross remains in the studio, along with Quincy and Lionel and a few others. Tom Bahler hears her crying softly. He asks if she is OK. “I don’t want this to be over,” she says.

Thanks to AW for the inspiration. This post is free to read so please share and ‘like’ if you liked it, and if you haven’t subscribed to The Ruffian yet, rectify this immediately. After the jump, a lovely Rattle Bag of brain food; things that have made me think, smile, shout and sigh.