Seven Underrated Forms of Diversity

Different Kinds of Difference At Work

Catch-up service:

Why Margaret Thatcher Didn’t Jump

The ‘Both Sides’ Problem

Notes on the Florentine Renaissance

The Good Enough Trap

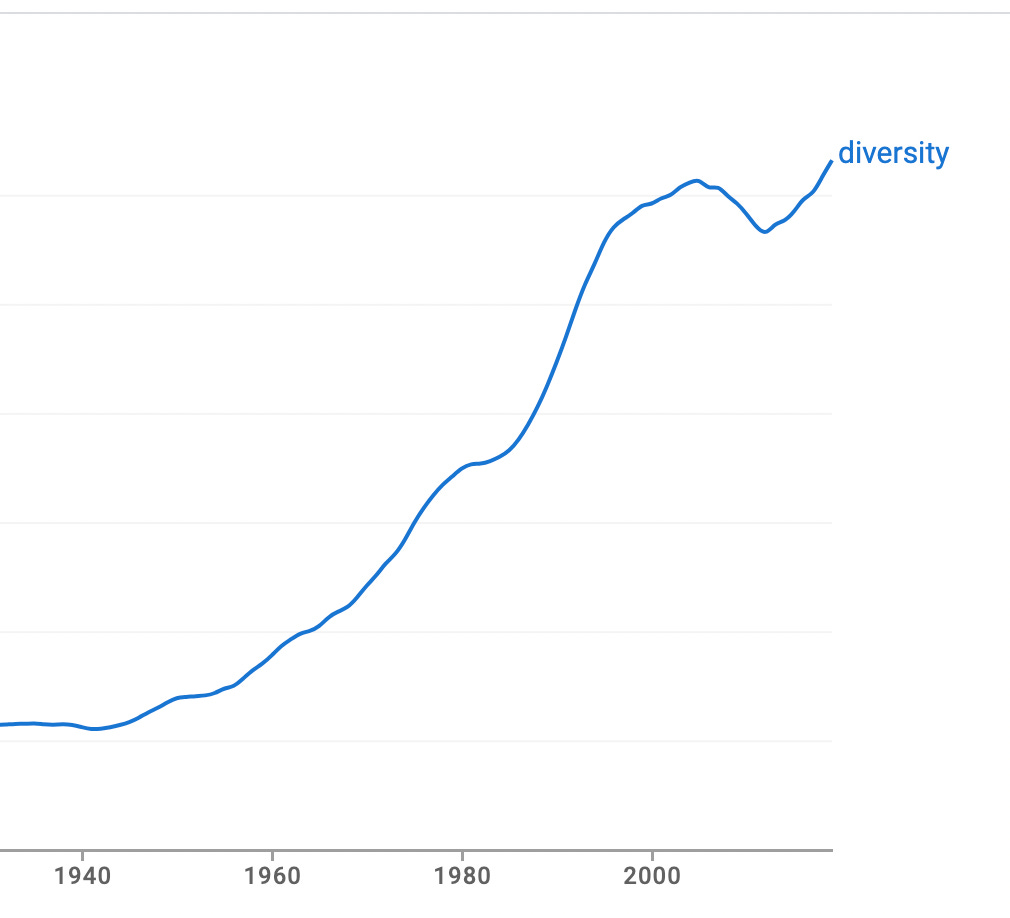

Every era has its master concept: a shared idea or aspiration to which the great and good must pay homage. For the Romans, it was “civic virtue”; for the Victorians, “progress”. For us it is probably “diversity”. The word has become ubiquitous, present in every corporate mission statement.

Diversity has an unambiguously positive valence. We celebrate diversity. This company is wonderfully diverse; this one, sadly not. Any institution which is not conspicuously diverse must be made more so, or risk seeming anachronistic. In recent years, the word has become more left-coded, but it is still more politically neutral than, say, equality.

As master concepts go, I think diversity is a pretty good one. It has its drawbacks, as when it’s used as an excuse for dumbing down. But the mixing-up of ethnicities, traditions and worldviews has generated a vast amount of cultural and economic value over the last 100 years, for a species that has spent much of its time on the planet in the violent defence of homogeneity. Diversity is written into the code of life itself. A planet which becomes less diverse in cultural or biological terms will be a less dynamic and interesting place.

I do think, however, that the sense in which we use the word is rather narrow. When organisations say they value diversity they almost always mean particular kinds of demographic diversity: race, gender, sexual orientation. But the principle of diversity can be understood and applied in a far greater - more diverse - variety of ways.

Here are seven kinds of diversity I think are underrated:

Cognitive Diversity. Since it was apparently not enough to argue for demographic diversity on moral or ethical grounds, the corporate world started to assert that it made for better business performance, as a greater range of perspectives was brought to bear on each problem. That case appears to have been wildly overstated and frankly it never made much sense: a group of middle-class graduates from elite universities is quite capable of sharing an identical outlook regardless of differences in ethnicity or gender. What companies should aim for is diversity of thought - of intellectual competencies and thinking styles (mathematical, verbal, systematic, creative, etc). That might include different perspectives derived from life experiences, but demographic diversity alone isn’t enough to deliver cognitive diversity because gender and race are not very accurate guides to how people think. (You also have to create a culture in which differences get expressed, see my book on productive disagreement.)

Class Diversity. Class gets downgraded or erased from the corporate discourse. This is partly because it’s less visible. Posters or pictures on a website can show men and women with differently coloured skin loving their lives in the office, but they can’t show someone who grew up on a council estate, went to a mediocre state school, and still made it to the C-Suite. (Well they can, but we won’t know their story). One significant divide in how people process the world is between those who went to university and those who didn’t, so if you value diversity of perspective, perhaps start there. Bonus: if you have a wider range of class backgrounds in your organisation, you’ll probably have more ethnic diversity too.

Agreeableness Diversity. A slightly awkward phrase for the simple idea that you should have a mix of nice people and well, less nice people. By the latter, I don’t mean you need any truly poisonous individuals on your team. I mean that you need people who can be abrupt and sometimes abrasive; who will prod and push at propositions until they’ve been fully tested; who will persist with a line of questioning after everyone else in the room feels awkward. Disagreeable people are terrible at charming their peers or superiors, and for that reason they often get filtered out in the hiring process or isolated at work, even when they’re brilliant at their job. But when allowed to be who they are, they can be worth billions. After a series of accidents and near-accidents involving Boeing planes, the company’s stock is in the toilet. A few years ago, its CEO spoke proudly about how he’d rid the company of “phenomenally talented assholes” - you know: those pesky engineers who whined on unreasonably about making the planes safe. The awkward buggers got replaced by management consultants with orthodontically perfect smiles and a nice line in conversation about ski resorts. Everyone got along really well.

After the jump: four more underrated types of diversity, plus my thoughts on The Dropout, plus a bumper harvest of juicy links.

Age Diversity. One reason the family unit has been such a universal and enduring institution is that it’s inherently age-diverse. The younger members learn from the older ones (albeit reluctantly sometimes) while older members are challenged and inspired (and annoyed) by the younger ones. Each generation brings different kinds of information and knowledge to the party: knowledge of the past, versus knowledge of how things are now. They see the world through different temporal lens and have different aspirations but each side gains from being around, and arguing with, the other. The same is true of other kinds of unit. Some organisations get stuck with age profiles that skew very old (Congress) or very young (ad agencies, Chelsea FC) and suffer as a result. As societies, some of our problems stem from Generation X parents being so keen to be thought of as young that they pander to the young while more or less giving up on thinking for themselves. Crucially, it’s the younger generation which suffers the most from this abdication of responsibility.

Ideological Diversity. Universities are the most obvious place where ideological diversity is currently lacking, as Jonathan Haidt and others have argued. But I think this is important to any organisation with a responsibility to the public and an aspiration to be non-partisan, from government bodies to the publishing industry to the third sector. Not all people are ideological in the strict sense of having a politically coherent worldview, but most have a set of cultural-political instincts that places them somewhere on scales like the liberal-authoritarian one. The fact is that the public is ideologically diverse, so if you’re not, you’re not going to serve them as well as you could. The first step is to get data. Carry out an anonymous ideological audit of staff and calculate the skew vs the population at large. Even if you can’t or don’t want to get rid of the skew, at least you’ll have a map of your biases. The most costly cultural mistakes happen when staff aren’t even aware of how unusual they are compared to the people they serve.

Optimism Diversity. By which I mean a mix of optimists and pessimists. A company full of pessimists would be a pretty depressing place to work (although to be fair, pessimists are often keen exponents of gallows humour). It would also be risk-averse, resistant to change, and eventually sclerotic. But a company staffed only by indefatigable optimists is disastrous. The tech industry sets great store on optimism and it’s probably true that founders need to be irrationally optimistic, otherwise they wouldn’t try in the first place. But founders should avoid the temptation to surround themselves only with people who think like them, and investors should be deeply wary of those who do. If you don’t believe me, I’ll introduce you to the next Elizabeth Holmes. She’ll have an irresistible proposition for you.

Sensitivity Diversity. This is related to agreeability, but it’s not quite the same. Ideally, you should be surrounded by some individuals who instinctively adapt their behaviour to what others are thinking and feeling, and others who are much more insensitive. Contrary to the prevailing wisdom that everything must be “talked out”, psychologists who study couples and families have found that if everyone is very sensitive to everyone else, relationships can become neurotic and fragile. It helps to have at least one or two members of the group who tend to be oblivious to the latest drama because they’re basically quite insensitive. When the political scientist Robert Axelrod modeled how opinions get formed in groups, he found that the faster that individuals change their opinions, the longer it takes for the group to reach a consensus. The result is a volatile system prone to wild swings of opinion. In any group or team, having a mix of the sensitive and insensitive can help reduce miscommunication, emotional volatility, and groupthink.

What other types of valuable diversity have I missed?

What I’ve Been Watching

The Dropout is a dramatised account of the Theranos/Elizabeth Holmes saga in eight parts. It came out in the US in 2022; I think it’s only arrived here more recently. Anyway, it’s on BBC iPlayer, and if you can access it, you should watch it. It’s the most intelligent, absorbing and enjoyable TV drama I’ve watched since Succession/White Lotus. I won’t say too much about it here other than to note that it features a wonderful, subtle performance from Amanda Seyfried as Holmes. I read the book, Bad Blood, a few years ago, which is also excellent but this is a very different experience. Almost inevitably, it makes you more sympathetic to Holmes. Having said, that it doesn’t spare her. I ended the series in a state of confusion, unsure how to judge her, which is exactly what I want from a work of art. In fact I thought the bit of moralising they did right at the end felt dutiful and not at the level of the rest of the series. It’s not just Seyfried’s show, by the way - the cast is superb, there’s so many killer performances, including and especially Naveen Andrews as Sunny. The script is first rate; serious, smart, compulsively paced, and playful, rarely more than an inch away from comedy (the creator and showrunner, Elizabeth Meriwether, created the sitcom New Girl). Check it out!

Rattle Bag

I watch/listen to Roland Fryer, an economist at Harvard, as much as I can. He’s an example of racial and class diversity; there are very few elite academics from poor black families. Fryer was raised in Texas by his grandmother; his father was an alcoholic, his mother left when he was very young. By his teens, he was in gangs. All this is to say that when he speaks about race, racism and policing, he does so with a particular kind of authority, although it’s not what he relies on - what he relies on is research and data. In this interview with Bari Weiss, he talks about the reaction to one of his most controversial papers, on the Ferguson Effect (from about about 22m:50s). In short, the paper found that when videos of police-on-black violence go viral, the police do less policing, with the result that many more black lives are lost to murder (out of the media spotlight). The paper did not go down well with his peers.

‘The Foxes and the Bears’. I found this Substack post on Putin’s recent reshuffle, from Professor Sam Greene, illuminating. Putin is a master of playing the internal power game. More than two years after Russia invaded Ukraine, which the experts said, not unreasonably, was a disastrous decision, it’s hard to avoid the depressing conclusion that he’s as secure as he’s ever been.

Trump has doubled his support among black voters since 2020 (and he did pretty well with them then). It’s May but we will soon be at the stage where it’s legitimate for Democrats to panic.

Unherd (via the excellent Tom McTague) publish a heroic profile of Keir Starmer’s chief political adviser, Morgan McSweeney, in which McSweeney argues that Starmer has major political differences with Blair. He doesn’t go on the record but you suspect that if he was going to write his own profile, it would look something like this. A week later, the New Statesman runs a piece by the head of Labour’s most influential think tank, saying the opposite. What’s under the bonnet? Well, it’s an old story: McSweeney was the undisputed consigliere; then Sue Gray joined. This may be just the beginning of a low-level civil war in the leader’s office, carried out in anon briefings. Btw I would gently suggest these guys stop being obsessed by Blair (leave that to me).

There are people who bang on about ‘woke’ too much but those who dismiss it as a fuss about nothing are at least as misguided. Here’s Ed West on the historians who are moving to erase the category of “Anglo-Saxon” for basically irrational reasons. You’ll probably learn some history, too, I did.

Thread on the travelling patterns of medieval kings.

Alex Massie addresses a question I posed on Twitter: should Scottish devolution be judged a success?

Inspired by the feud between Drake and Kendrick Lamar, this is a lovely post about the history of “answer songs”.

Chart of the week: the rise and fall of American serial killers.

A former Barcelona footballer who moved to a club in Romania is being investigated over claims that he actually sent his twin brother to play for him. The notion that you’d need a DNA test to sort this out might be the craziest part.

I linked to his Twitter feed a while back but this is a nice interview with the chief framer at the National Gallery.

Kenneth Clark (‘Civilisation’) tries to get his head around modernist art with the help of John Berger.

The Strong Songs podcast breaks down great pop songs to their elements. This is a very good edition on Blondie’s Heart of Glass, which makes you appreciate, in particular, what a skilful, subtle vocalist Debbie Harry was. Also, that lyric “mucho mistrust” is so silly and so perfect.

This is a treat. Bill Nighy on five favourite things (film, book, city…). Every choice is interesting and he talks so beautifully about each one:

Nice one - and couldn't agree more that organisations, and all of society, benefits from maximal diversity (even sociopaths have a valuable role, as long as they stay within the law). How would you propose that companies achieve the personality-based forms of diversity when hiring? And how to balance the need for maximal diversity with fairness and the top candidate getting the job?

And one needs to be varying degrees of diverse within oneself.