Successful Politicians Are Pattern-Breakers

How Moderates Win In a Hostile Environment

Catch-up service:

Is Civility a Fantasy?

A Studio 54 Immigration Policy

10 Ways To Buy Happiness

Fake Debates and Late Converts

Suicide as a Bargaining Tactic

Notes on the Greatest Night In Pop

Thanks to everyone who came along to see me talk John & Paul in Durham last night. I’ll be doing the same in Sheffield this afternoon, as part of the Off The Shelf Festival. Come along if you can.

This week: a theory of how to do politics in an anti-politics age, plus notes on the Gaza deal, plus a fabulous Rattle Bag. This post is ‘too long for email’ so click on the title to read online. Please forgive me if there are some errors, I’ve been writing this on the road.

It has not gone unremarked that Americans with different political views distrust and dislike one another. This is usually framed as a 50:50 division between supporters of the two main parties: two vast armies, fighting for entirely different values and policies, facing off in a cold civil war. Look under the surface, however, and something more complex is going on.

First of all, it’s not true that the America’s population can be easily divided into ideological camps, and while such questions are much debated among political scientists, there’s a good case that Americans overall haven’t become more extreme or rigid in their views. What’s happened is that America’s political culture has been poisoned by a minority of ideologues on either side.

Ideologues, in the sense used by political scientists, are voters who have consistent beliefs, organised into recognisable patterns. If you know they’re against immigration, you can predict they’re also anti-abortion and pro-gun. Non-ideologues either have no strong views on politics, or they have strong opinions which don’t follow a standard template.

Although the number of ideologues has been growing (they’ve doubled over the last twenty years) they still represent only about a fifth of voters. Most Americans aren’t as structured in their views and don’t easily fit into Democrat or Republican boxes. Many of them are ambivalent about the most divisive issues, like abortion. Plenty of them have a mix of liberal and conservative positions.

Ideologues have disproportionate influence and power, however. They shout the loudest and generate the most political content. They’re also the ones funding and running political parties. (Politicians are more ideologically consistent than most voters, partly because they have to be to get ahead but also because many of them are predisposed to be).

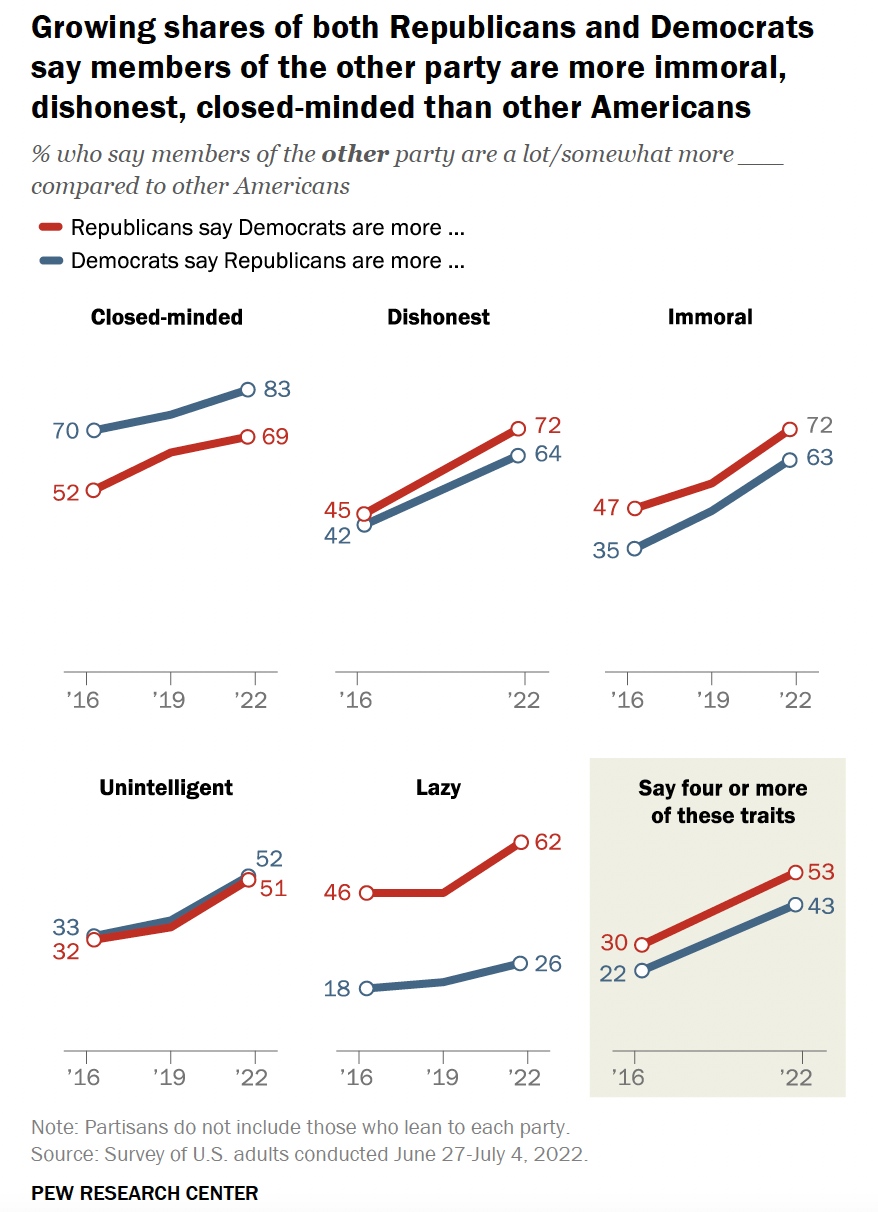

Another reason that ideologues matter so much is that they exhibit more anger, distrust and hostility towards the other side - and those feelings are contagious. While most voters don’t share the political fervour of this minority, they have absorbed their animosity. Voters who identified as Democrat or Republican didn’t used to have strong feelings about those who leaned the other way - it was just politics, after all - but they do now. “Affective polarisation” has increased and spread throughout the population.

High levels of negative feelings about those on the other side have become normal. This is true even among independents. Most independents lean toward one party or the other. Between 1994 and 2018 those with “very unfavourable opinions” of the other side increased from 8% to 37% among Democratic leaners, and from 15% to 39% among Republican leaners.

In short, ideological polarisation is a minority pursuit, but affective polarisation is a national pastime. Most voters don’t actually have very strong views on economic or social policy and couldn’t necessarily point you to major differences in the parties’ platforms, but they have a strong feeling that the other side is wrong and bad. They don’t care much about politics but they know who they don’t like.

In Britain, things are a little different. Whenever I hear people say British politics is “polarised” I wince a little. To polarise means to divide into two opposing groups. The term is lifted from America, where nearly everyone votes for one of two parties, and it doesn’t make sense here.

In fact the salient feature of British politics in the last few years has been a decline in the popularity of both main parties and a fragmentation of the vote. Our slightly milder but still fractious political debate takes place between a series of cultural-political clusters which don’t line up neatly with institutional affiliations. There’s more than one way to cut the cultural cake but More In Common’s typology is a useful one (numbers here).

Parties aiming for a parliamentary majority need to straddle different clusters, which is far from impossible. Without America’s party binary, British voting patterns are inherently more fluid. The differences between most voters are not necessarily wide: most Reform voters favour same-sex marriage, for instance, and are vaguely in favour of diversity, even if they want immigration to come down (the latter being true of most voters). I hear a lot of politicians and pundits urging Keir Starmer to focus on his “natural” voters rather than on those tempted by Reform, but that would represent a tragic failure of ambition. Nigel Farage certainly doesn’t accept that he can’t win over left-leaning voters.

There is a sense of pessimism among centrist commentators - a feeling that British voters are both irretrievably atomised and radicalised. I’m not convinced by this. Pollsters who spend a lot of time doing focus groups tend to over-estimate the extent to which people care about politics, and also how miserable and angry voters are. Focus groups are socially awkward events, and one of the main ways British people bond with each other is by having a good moan.

My guess is that, as in the US, a substantial minority of hardliners on left and right generate most of the public anger and animosity, which breeds a listless but pervasive distrust and cynicism among voters at large. (More of the hardline anger comes from the right than the left - see the “Dissenting Disruptors” in More In Common’s framework, a very frustrated, verging-on-anarchist group of voters which now constitutes nearly a fifth of the electorate.)

In America and Britain ideologically driven voters are in the minority but on the rise, and they have an outsized democratic impact. America, in particular, places a lot of power in the hands of ideologues, via the presidential nomination process. The Republican Party was famously radicalised by Trump, and the Democratic electorate is a lot more left-wing than it was when Joe Biden won the nomination.

We might even say that the future of democracy depends on these voters. So it’s worth taking a closer look at how they behave. I found this new paper on disagreement among ideologues very interesting. It’s by a political scientist, Tadeas Cely, who studies America’s political polarisation. Cely adopts the definition of “ideology” coined by the godfather of modern political science, Philip Converse: “a system of explicit and unequivocal political beliefs”. Ideologues are people who are politically sophisticated enough to know, in Converse’s phrase, “what goes with what”, and stick to the pattern of beliefs that they share with their cohort.

Cely ran a survey of a couple of thousand American voters in which he presented them with the opinions of a hypothetical voter on controversial political issues (like immigration and gun control). The hypothetical voters was either liberal, conservative, a mild centrist, or someone with an unusual mix of strongly held views - a “messy” belief system. The respondents were classified in the same way, according to the firmness and consistency of their policy positions.

After viewing the hypothetical voter’s opinions, respondents were asked to rate how warmly they felt about this person, using a hundred point “thermometer” scale. Cely found that disagreement between ideologues produces more animosity than other disagreements. Not just a bit more - way more. When two ideologues clash, they hate each other about three times more intensely than after disagreeing with people with equally strong but “messy”, non-patterned beliefs, and four times more than with mild-mannered centrists.

Cely’s analysis of how animosity gets triggered is fascinating. In a second survey, he used the same model and told participants that their fictional interlocutor held views on two additional issues (student debt and Gaza ceasefire) without saying what those views were. What he found is that those “unrevealed” opinions increased the hostility of the disagreement. Why? Because the ideologues “filled in the blanks”. After having seen the person’s view on abortion, they just knew what this person would say about Gaza. And it made them furious.

We might put it like this: disagreement between ideologues is metonymic. The part stands in for the whole. As soon I know one of your beliefs, I know all of them. More than that, I know what kind of person you are: you’re somebody I hate.

In a sense the whole political environment now operates metonymically. With so much competition for eyeballs, the amount of attention voters spare for politics is smaller than ever, so they make thin slice judgements based on content produced by ideologues on their own side - content which highlights the most outrageous and objectionable ideologues from the other side. Voters extrapolate from the worst to the whole.

If you’re non-ideological, moderate politician, you need to be able to speak to the ideologues on your side.1 They’re a growing group of voters, overrepresented in the centres of power, who set the tone of the wider debate because of how noisy they are and how intensely they dislike the other side.

But if you only speak to the ideologues, you get trapped inside the ideologue’s rigid belief system, which makes it harder to reach the non-ideological majority. You’d also be faking it, which is quite easy to spot. The trick is to adopt enough of the pattern to avoid being denounced as a traitor by your own side, while adopting one or two elements beyond it which show that you’re not a captive of it.

Pattern-disruption is important both to be noticed in the first place - given that voters are predictive processors with scarce attention for politics who simply screen out familiar patterns - and to prove that the politician is their own person rather than a robot controlled by his or her party or faction. Most voters have ‘messy’ sets of beliefs and they respond to politicians who mirror them in that sense.

This is not to be confused with putting together a ragbag of positions based on whatever policies do well in polling. Ambitious politicians need a set of positions that are internally coherent, grounded in a story about how the country needs to change (beyond ‘get the other guy/party out’). But it can’t be a matching set; it has to be new or surprising in some way.

I’m not suggesting anyone emulate Trump’s brazenly offensive manner or authoritarianism, which have done so much to toxify American politics. But consider how his unlikely success in 2016 was based on a pattern-breaking combination of policy positions: strongly anti-immigration, opposed to foreign wars, pro tax-cuts, pro-Medicare. Consequently he was regarded by voters as less conservative than most Republican candidates, and more moderate than his opponent, Hillary Clinton.

Or recall Boris Johnson’s greatest political victory. He won the 2019 general election by mixing cultural authoritarianism (Get Brexit Done) with economic interventionism (”levelling up”). That broke the expected patterns and knocked down the Red Wall. Johnson and Trump were very different in style, even if they often get lumped together but it’s important to note that successful politicians practice strategic pattern-disruption at the level of tone as well as policy.

For instance, a moderate politician might not want to present as moderate. “Moderation” by itself doesn’t make noise, and at worst, it signals complacency and weakness. (If Josh Shapiro, the popular and moderate governor of Pennsylvania, wants to win the 2028 nomination, he will have to lean into his inner Bernie.) But pure “radicalism” keeps you in the ideologue box. A “combative moderate” uses the rhetorical intensity of ideologue wing to moderate ends. Hence the current incarnation of Gavin Newsom.

Zohran Mamdani is a pattern-breaker. Progressives often come across as stern and scolding; Mamdani is relaxed, funny, a good listener. He is a radical leftist who wears a smart, some might say conservative, suit and tie. His wire-crossing may end up extending to more than style or personality; it will be interesting to see if he ends up adopting a politically heterogeneous, ‘messy’ mix of policies once in office, as Ken Livingstone, similar in some ways, did in his first, successful term as London mayor.

It is probable that the share of ideologues in the electorate will continue to grow, as social media makes political discourse ever more algorithmic and ever more angry. Politics may eventually become a clash of armies with rigid, unyielding, static positions. But we’re not there yet, and we probably won’t be for quite a while. It is still possible for imaginative politicians to disrupt established patterns and create new ones, and plenty of space for them to do so in the middle ground. What they can’t afford to be is predictable.

Next: my thoughts on the Israel/Gaza peace deal, plus a very juicy Rattle Bag of excellent things: good news on climate change; how to find time to read; the ad industry’s fake diversity; why warm countries are poorer; what I’ve been watching and listening to.