Suicide As a Bargaining Tactic

The Evolutionary Roots of Misery Signalling

Catch-up service:

Notes on the Greatest Night In Pop

Rationalist Cults of Silicon Valley

The Data Says We’re Doing Fine So Why Are We Furious?

How Humans Got Language

The Diderot Effect

27 Notes on Growing Old(er)

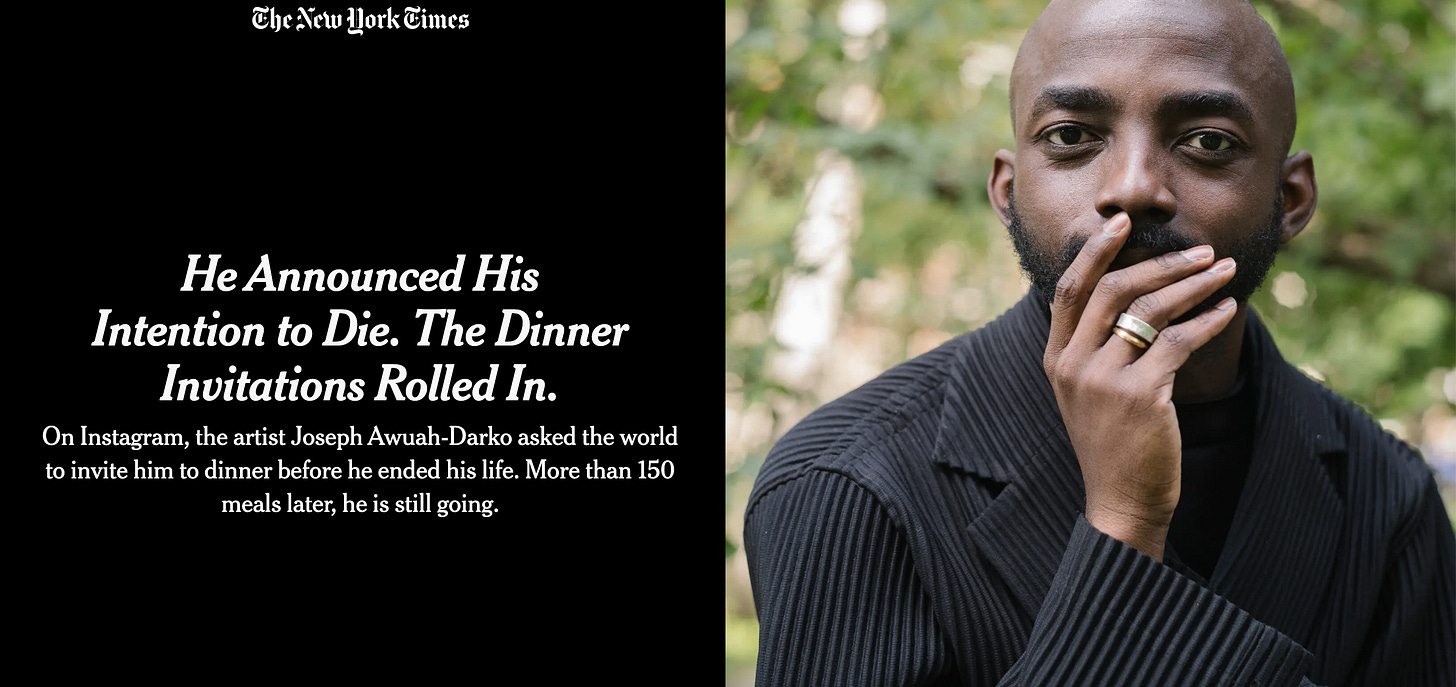

In December last year a young artist called Joseph Awuah-Darko took to Instagram to declare his decision to end his life. He posted a video of himself in tears, followed by an artfully produced video montage of happier moments: Awuah-Darko afloat in a sun-dappled swimming pool; reading a book in a treehouse; standing thoughtfully on a bridge; presenting the camera with an origami bird. In the accompanying text, which began with a quote from Joan Didion, he explained that the burden of existence had become unbearable. He cited depression, struggles with debt, violence in the news, the rise of AI, and his bipolar disorder, which made his lows very painful. He announced that he had moved to the Netherlands to pursue assisted suicide.

This post elicited abundant sympathy. A few days later he posted again, this time to launch “The Last Supper Project”. Awuah-Darko said that while he was navigating the Dutch euthanasia bureaucracy, he wanted some company. He invited his followers to cook him dinner at their home. All you had to do was click on his bio, find a slot in the calendar, and he’d turn up at the appointed hour. “I want to find meaning again with people while I have time still left on earth,” he said.

Thousands took him up on it. According to a recent profile of him in the New York Times, Awuah-Darko has now attended over 150 dinners, across the Netherlands, and in Antwerp, Berlin, Paris and Milan. He talks about life, death and depression with his hosts over dinner, while taking photos and video for his Instagram account. As a side project, he is the star guest of a series of dinners in Amsterdam “for the emotionally fluent and the existentially undone”, hosted by a fashion designer. Places are $175 per head.

It sounds grotesque, except that people do seem to find solace in his story, and appreciate the opportunity to talk about the dark side of living. Awuah-Darko’s followers - he now has over half a million on Instagram - adore him. “Your presence on this app has been so healing and educating for me”, says one. Another says, “Having death close sometimes feels like a friend by our side, helping us live more fully and love more deeply.”

Still, there’s something unavoidably absurd about his endeavour. The New York Times reports that Awuah-Darko is very unlikely to be granted euthanasia in the Netherlands, since doctors who perform such procedures must be able to show that the patient’s suffering is unbearable. A Dutch professor of medical ethics states the obvious: “He’s having too much fun”. Mental health experts are appalled, particularly because bipolar disorder is treatable and manageable. Awuah-Darko, the scion of a phenomenally rich Ghanaian family, is now equivocal about whether his stated intention is meant literally, although most of his followers seem to believe it is.

It would be easy to call Awuah-Darko a fraud, which needn’t detain us from doing so, but his case does raise deeper questions. It’s a florid example of what you might call misery signalling: using exaggerated claims of mental distress to win attention and status on social media. Awuah-Darko’s performance of suicidal depression is so theatrical that you almost suspect deliberate parody (perhaps that’s his true artistic project) but there are plenty of less on-the-nose examples, from high-profile journalists to the countless teenagers who would once have made flamboyant threats of self-harm only to their parents, but who can now do so online to a wider audience.

Let’s agree that most people who declare suicidal feelings are sincere and ought to be taken seriously. It can also be true that in an online culture that rewards dramatic self-disclosure, young people in particular have incentives to exaggerate and amplify their struggles in order to acquire social capital in the form of likes, shares and follows (and profiles in the New York Times).

So we can add another social ill to the growing list of charges against short-form video. But what I find fascinating about this behaviour is that, in its most fundamental form, it isn’t new at all. Declarations of misery and suicidal intent, and suicide attempts, have long been used as social signalling. Indeed, according to one well-established theory from psychology, that’s what suicidal behaviour is.

One of the reasons I like evolutionary psychology is that it takes human behaviours which seem natural or inevitable and asks, why? Why do people kill themselves? From an evolutionary standpoint, suicide represents a profound puzzle. Natural selection should have eliminated behaviours that lead directly to premature death. No genes can be passed on from the other side. Yet suicide occurs across all human societies, and has persisted throughout the history of our species.

According to Edward Hagen, a leading evolutionary psychologist, the answer to this conundrum is that most suicidal behaviour isn't actually about dying. It's about negotiating. Hagen argues that both depression and suicidality evolved as strategies to compel others to renegotiate social arrangements. He calls this "the bargaining model of depression."

In the ancestral environment, humans lived in small, highly interdependent groups. If you were being treated badly, your options were limited. Switching social partners was difficult to impossible - you couldn’t just leave town or find a new group to hang with. Any outright confrontation risked violence and physical harm.

So when someone found themselves trapped in a situation where they felt others were benefiting from their efforts, but they were receiving little in return, the most viable option was to advertise their distress by withholding social contributions, thereby forcing others to recognise the problem.

Hagen proposes that depression functions "somewhat like a labor strike”. The depressed individual puts their value to the group at risk, compelling others to renegotiate the social contract. The characteristic symptoms of depression—loss of interest in activities, withdrawal from social roles—effectively communicate that the status quo is unsustainable, that things can’t go on as they are.

Within this framework, suicidality represents the ultimate bargaining chip. A suicide threat signals to the group that they may permanently lose this person's contributions unless something changes. Imagine life without me!

Crucially, Hagen notes that for this strategy to work evolutionarily, suicide attempts must be survivable most of the time, so as to allow for negotiation.1 The evidence supports this: most people who attempt suicide do warn others of their intentions, and choose methods with relatively low lethality. For men, only one in ten suicide attempts are completed; for women, one in thirty. There is obviously a fine balance: a suicide threat or attempt must also be somewhat credible so that others believe it might work. A suicide attempt is a ‘costly signal’.2

The bargaining model explains why depression is nearly twice as common in women, and why women have a much higher ratio of suicide attempts to suicides. In ancestral environments, Hagen says, women moved with their husband’s family after marriage, and ended up surrounded by non-relatives (in-laws). That made them more vulnerable to exploitation and abuse. Lacking the strength of men, physical confrontation was generally a bad idea (Hagen's data shows that when you control for upper body strength, the sex difference in depression largely disappears). But they did have reproductive resources, which made their bodies valuable bargaining chips in social negotiations. Thus they relied more on this costly signal to secure fair treatment.

Hagen and his fellow researchers have found evidence for the bargaining theory in the ethnographic record. Among the Kaluli of Papua New Guinea, the Quechua of Peru, and various other traditional societies, depressive states and suicide threats are explicitly understood as appeals for social intervention and reparation - and the tactic is an effective one. When someone becomes severely depressed, community elders investigate who is at fault and work to correct the situation. The anthropologist Michael Brown observed that among the Aguaruna of Peru, suicide is used to "express anger and grief, as well as to punish social antagonists."

In that sense, misery signalling isn’t a product of phone culture, but just the latest expression of an age-old social tactic, both instrumental and deeply felt. Shakespeare knew about it, of course. He wrote about a young scion of a wealthy family who uses suicidal ideation to communicate that something is rotten with the world. Given access to a camera and Instagram, Hamlet’s reflections might have been less profound. Still, regardless of what I think of Awuah-Darko, I’m glad that he has so far chosen to be rather than not be. His signalling worked a treat. The rest is supper.

Further reading and listening for Hagen: his paper on the bargaining model of depression; interview with Chris Williamson; interview with David Pinsof and Dave Pietrazewski.

After the jump: good news on human progress; a cure for overthinking; how the tariffs are going; a note on the Minneapolis shooting (and its connection to the Zizians); a great poem about why we need boundaries; why one of the most important thinkers of all time was also very unproductive; how to contemplate a painting; a contender for the greatest Dylan song…and more!

Paid subscriptions are what makes the Ruffian possible. Please consider upgrading if you haven’t already.