The best reason to believe Woody Allen is innocent is the simplest one

How we form opinions on limited information

Catch-up service: Bernstein vs Gould

The problem with ‘educate yourself’

Stories are bad for your intelligence

Woody Allen’s latest film, Coup de Chance, was warmly received at its premiere in Venice, this month. I’ve seen it described as his best since Match Point, which to me is not very encouraging, since I regard Match Point as the worst movie he ever made, and a contender for the worst movie anyone has ever made. But I’m glad he’s still working.

Not everyone feels this way. Many believe Allen is a monster who should be ostracised from decent society rather than receiving a standing ovation in a Venetian theatre. The accusation that he is a child molester has increased in volume since 2014, when, following a lifetime achievement award to him at the Golden Globes, his adopted daughter Dylan and son Ronan reignited a claim first made by their mother Mia Farrow in 1992: that Allen molested Dylan when she was seven. Dylan made the claim directly, for the first time, in an article for the New York Times. These are its opening paragraphs, which, I warn you, are hard to read:

What’s your favorite Woody Allen movie? Before you answer, you should know: when I was seven years old, Woody Allen took me by the hand and led me into a dim, closet-like attic on the second floor of our house. He told me to lay on my stomach and play with my brother’s electric train set. Then he sexually assaulted me. He talked to me while he did it, whispering that I was a good girl, that this was our secret, promising that we’d go to Paris and I’d be a star in his movies. I remember staring at that toy train, focusing on it as it traveled in its circle around the attic. To this day, I find it difficult to look at toy trains.

For as long as I could remember, my father had been doing things to me that I didn’t like. I didn’t like how often he would take me away from my mom, siblings and friends to be alone with him. I didn’t like it when he would stick his thumb in my mouth. I didn’t like it when I had to get in bed with him under the sheets when he was in his underwear. I didn’t like it when he would place his head in my naked lap and breathe in and breathe out. I would hide under beds or lock myself in the bathroom to avoid these encounters, but he always found me. These things happened so often, so routinely, so skillfully hidden from a mother that would have protected me had she known, that I thought it was normal. I thought this was how fathers doted on their daughters. But what he did to me in the attic felt different. I couldn’t keep the secret anymore.

After this was published, a scandal which had dogged Allen’s career came very close to ending it altogether. You can see why: Dylan’s account elicits a visceral reaction of disgust in any reader, including me. If what she says is true I’d be more than glad for Allen to be publicly shamed and prosecuted. But I think it’s unlikely to be. Now, my opinion on this case is probably worth about as much as yours - that is, not very much. I haven’t performed a rigorous study of all the evidence or interviewed any of the people involved. But we often hold firm views on complex questions, where we have some but not all the information, and when the question is as highly charged and controversial as this one our opinion tends to fall into one of two polarised camps. Sometimes it’s worth reflecting on how we got there.

In this case, I know that the two separate investigations made in the aftermath of the claim concluded that Allen did not abuse Dylan. Hadley Freeman has written good summaries of the evidence for Allen’s innocence, most recently in the Sunday Times last weekend, and previously in the Guardian, for example this and this. Here I’ll just note that the paediatrician who supervised nine interviews with Dylan, carried out by female social workers who specialised in child sexual abuse, concluded that Dylan had either made her story up or been coached into it by her mother.

None of this amounts to conclusive proof Allen didn’t do it. It’s possible to construct a plausible argument that he did, from the reams of evidence and counter-evidence, claims and counter-claims. What’s more, the knowledge of what various investigators concluded doesn’t have the force of Dylan’s testimony. Intuitively, it just seems very unlikely that a girl would invent such a horrendous allegation and persist with it in adulthood.

It makes sense for most of us to rely on simple principles or rules of thumb when forming judgements on information-dense topics. I could spend many hours reading the arguments that the 9/11 was an inside job, or I could observe the breathtaking incompetence with which the Bush administration prosecuted the Iraq war and conclude it’s unlikely to have pulled off such a complex operation and cover-up quite so effectively. So I don’t mind simplistic arguments; in fact, I prefer them, since the addition of layers of complexity often serves to obscure basic or common sense truths. But in the Allen case, Dylan’s testimony, powerful as it is, doesn’t convince me of Allen’s guilt, because I can’t get over my own simplistic reason to believe in his innocence: he’s not the type.

In a recent interview, the economist Roland Fryer recalled the advice of his tutor: “Life is all about who gets to claim the null hypothesis.” The null hypothesis, in non-technical terms, is the default; the normal state of affairs. It’s what we should expect, all other things being equal. Many arguments arise from the parties starting from different null hypotheses. For instance, the implicit null hypothesis of the left is that there is all this wealth in the world; the question is why it’s unequally distributed. The right’s null hypothesis is that nearly everyone in history has been poor, so the question becomes why there’s any wealth at all.

The null hypothesis of those who believe in Allen’s guilt is that when a man has been accused of doing a horrible thing by a woman, he probably did it. This is by no means a bad starting place. I agree that Dylan’s testimony is serious evidence that Allen is guilty. But I think there’s a different null hypothesis, which for me precedes that one and subsumes it. It’s this: it’s extremely unlikely that anyone with Allen’s track record would commit such an unspeakably appalling crime, as a one-off.

As I understand it (and my epistemic confidence on this topic is low; if you’re a criminologist or you know the literature, feel free to correct me) when men commit serious sexual crimes, they usually do so as part of a pattern of abuse. Child molesters, in particular, are compulsive victim-finders; Jimmy Savile being a notorious recent example. Rumours followed Jimmy Savile around for years before they exploded in the wake of his death, just as rumours of a different kind trailed Harvey Weinstein.

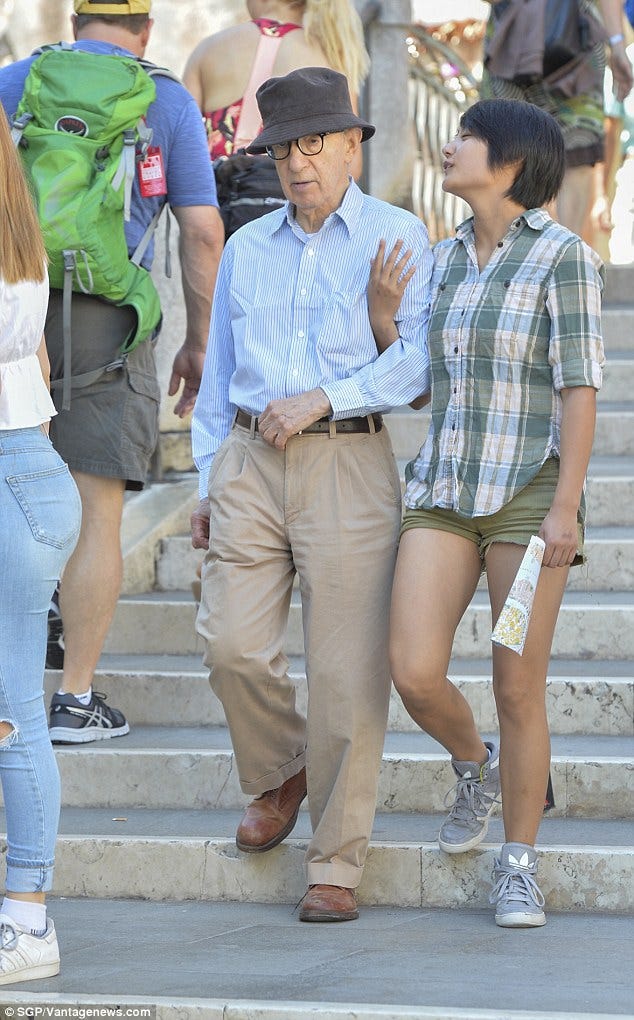

No such rumours have ever attached themselves to Allen. This one alleged incident aside, Allen has never been accused, in public or in gossip, of any kind of impropriety. None of his other children have alleged abuse. He raised two daughters with Soon-Yi, his wife. Bechet and Manzie don’t have much of a public profile but appear to be happy young women, fond of their father. Professionally, Allen worked with hundreds of women, without any impropriety ever being alleged or even hinted at. By Hollywood standards, his record is rather exceptional.

I assume that anyone who did to Dylan what Dylan has claimed Allen did would be a profoundly sick individual. Sickness like that tends to manifest itself in multiple, sprawling ways. As it is, to believe in Allen’s guilt we must believe that an individual with no history of abuse or mental illness committed this one act - an act deeply revolting to the natural instincts of the vast majority of fathers on the planet - and then returned to his otherwise peaceable, loving, well-ordered life. It could be true. Human behaviour is endlessly various. But how likely is it?

We’re not very good at estimating probabilities; we tend to over-estimate the likelihood of very rare but easily imagined events like plane crashes and lottery wins, and under-weight more abstract evidence like the data which tells me the odds of this plane crashing are almost zero. This is where I think a little Bayes (for that’s all I have) comes in useful.

I’ve told this story before but it’s particularly illustrative here. In 1989, when the HIV-AIDS epidemic was ravaging the US, the scientist and writer Leonard Mlodinow took a call from his doctor, to report the result of an HIV test. The test had come back positive. The doctor told Mlodinow that meant it was highly likely he was infected with the virus, and that he would die within ten years. The test was known to produce a false positive result in only 1 in 1000 samples.

After recovering from the shock, Mlodinow used his understanding of Bayes to conclude that the doctor was wrong. The odds of his being uninfected were a lot better than 1 in 1000. Why? Well, Mlodinow was heterosexual, monogamous, and not a drug user. That meant the prior probability of him being infected with HIV, based on epidemiological data, was about 1 in 10,000.

Mlodinow had one piece of information telling him he was probably infected. But he also had all this other information telling him he was incredibly unlikely to infected. So he was faced with two unlikely, mutually exclusive possibilities - 1) The test is wrong 2) He had contracted HIV. Crucially, the second possibility was much more unlikely than the first. Numerically, there was a 1 in 1000 chance of the test being wrong, but there was a 1 in 10,000 chance of Mlodinow being positive in the first place.

Run that through Bayes’ theorem and it implies only a 1 in 10 chance Mlodinow was infected.1 That’s not nothing - the positive test definitely changed the likelihood Mlodinow had HIV. But it didn’t do so by nearly as much as the doctor assumed. The doctor was working with the wrong null hypothesis, or in true Bayesian lingo, the wrong “prior probability”. He had failed to absorb the fact that Mlodinow was vanishingly unlikely to have contracted AIDS in the first place, and that one blood test, even one with a small number of false positives, was not nearly enough to conclude he was carrying the virus. As it turned out, Mlodinow wasn’t infected.

This is how I think about the Allen case. To me, Dylan’s claim is like Mlodinow’s HIV test. It’s an alarm bell. I take it seriously - it raises my estimated likelihood that Allen is an abuser. But I weigh that piece of evidence against all the circumstantial evidence which points the other way (and the evidence of the investigations). That means judging the relative probabilities of two unlikely and mutually exclusive possibilities. It’s unlikely Dylan would have made this up, and it’s unlikely that Allen would have committed such an act. But which is more unlikely?

To my mind, the chance that an individual like Allen would have committed such a heinous one-off act is much smaller than the chance that Dylan’s testimony is false. “Believe the accuser” is good working assumption. All claims of sexual abuse should be taken seriously because the vast majority of them are true. But even the most ardent advocates for that principle would admit to exceptions. Some alarms turn out to be false positives.

This post continues after the jump, where I take a look Allen’s relationship with Soon-Yi (often cited as evidence for his guilt), discuss the likely explanation for Dylan’s testimony, and reflect on which kinds of evidence shape reputations. If you’re not a paid subscriber yet, do give it a go…it’s very easy to sign up.