The differences of minor narcissists

Why do political movements splinter into antagonistic factions?

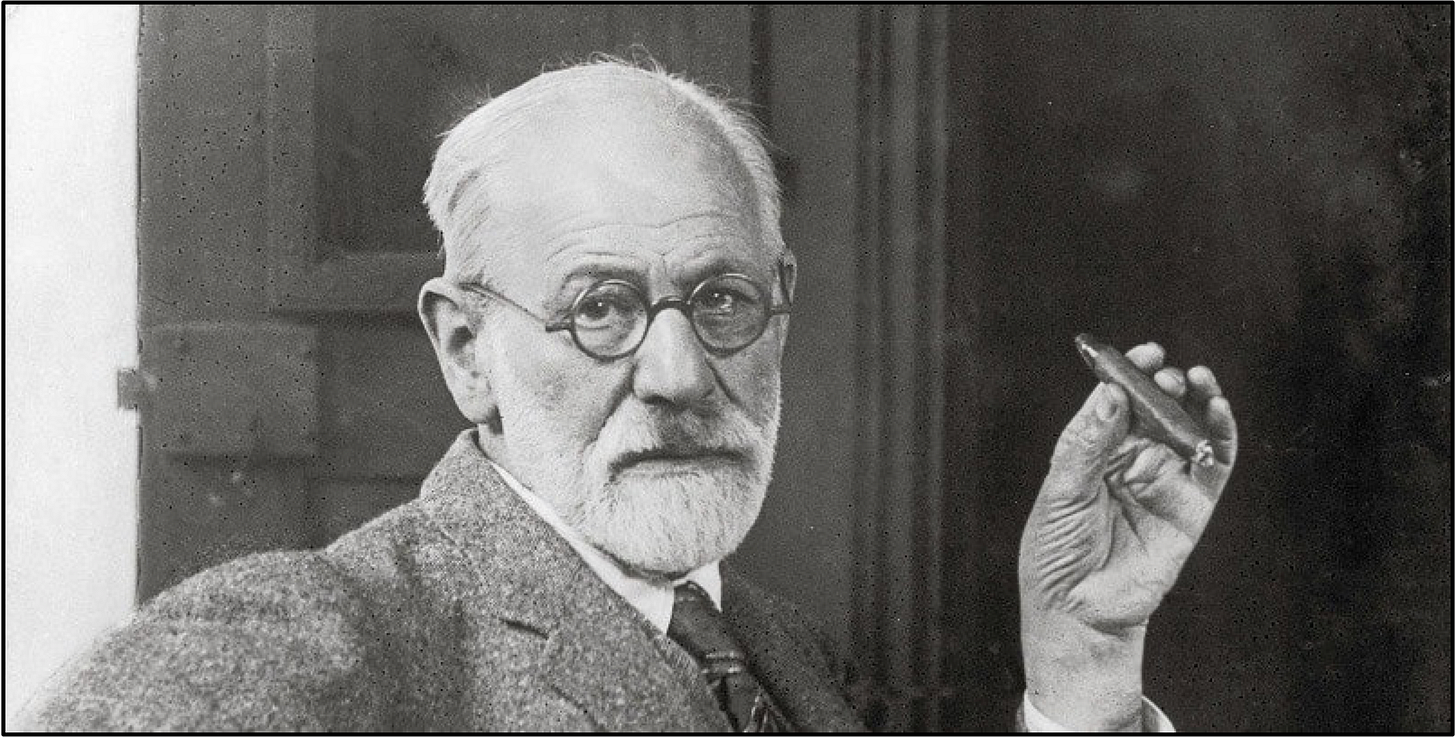

Dr Freud gives us a pitying look.

This is Part 1 of a two-episode mini-series.

Last May, when Labour languished in the polls and Boris Johnson seemed unassailable, I posted a thread arguing that the Labour leader Keir Starmer might yet turn things around. I didn’t say he’d win the next election or anything quite so rash - I just gently suggested things might look better for him in a few months. As it turns out, they do. Labour leads the Tories, and Starmer leads Johnson, both by considerable margins. I’m not just telling you this to advertise my prescience - which, let’s be honest, has not always been 100% reliable - but because I’m interested in the reaction my bland conjecture provoked from the Twitter left at the time. In a word: fury.

I didn’t expect people to agree, but I wasn’t prepared for such a highly charged response. Leftist tweeters rained down cackling derision on me for even thinking such a thing. Some seemed genuinely indignant. This was odd. These were, ostensibly, Labour supporters. You imagine they’d prefer a Starmer government, however inadequate, to a Johnson one. Even putting that aside, I wasn’t making a value judgement about whether Starmer should succeed, but a dry empirical one about whether he would. Yet people weren’t just disagreeing with my hypothesis; they were angry that I’d made it. Like T.S. Eliot after reading Hamlet - OK, not totally like that - I was left bewildered by this apparent excess of emotion.

It’s a truth often observed without being satisfactorily explained: members of a political group reserve their most passionate animosity for those on their own side. (I don’t mean animosity towards me, in this example, but Starmer). The far left makes ritual denunciations of the Tories but you can tell what really excites it is the opportunity to attack Labour moderates, and what really upsets it is any possibility the moderates will succeed. It’s not a peculiarly British phenomenon: you see a similar dynamic among US Democrats and probably in the politics of other countries I know even less about. Political animus is felt most keenly between political neighbours.

Is this caused by politics or does it have deeper roots - is it a manifestation of human psychology?

There is a paradox in our attitude to human difference. We know from history and observation that people are often mistrustful and hostile towards those from different cultural and religious backgrounds. You might expect this hostility, if unmitigated, to increase in proportion to the difference, perhaps to the point it explodes into violence. In 1993 the political scientist Samuel Huntingdon published an article, later a book, based partly on this premise. He argued that future wars wouldn’t be fought between states competing over territory, or ideology, but between groups which are radically different from one another in culture, such as China and America. Huntingdon called his thesis “the clash of civilizations”.

In 1998, a Turkish political scientist called Türkkaya Ataöv published an elegant refutation of Huntingdon. He pointed out that many, if not most of the world’s conflicts were between people from the same civilisation, and the same culture. In Rwanda, Hutus committed genocide against Tutsis; both groups were comprised of Christians who spoke the same language and married into each other’s families. Ataöv also cited conflicts in Northern Ireland, India and Pakistan, and Sunni-Shia fighting in the Middle East. After a survey of historical conflicts between closely aligned groups, Ataöv offered a psychological explanation: that we turn neighbours into enemies because we need enemies to tell us who we are. This is from his article:

We tend to externalize the bad characteristics in us and to project them onto others. When we later come across them in others, we no longer recognize them as our own. The interaction of neighbors may be a good example. When their relations are pleasant, their desirable parts come to the fore. When disagreements rise, differences get the upper hand, and minor differences are then magnified. Even if there are no minor differences, groups tend to create them.

Groups seem to be obsessed with the enemy, want to preserve the gap between themselves and the others, and do not want to be "contaminated" with arguments or even documentation coming from their adversaries. The enemy is preferably seen within the framework of a stereotyped image. The enemy is also needed to complete one’s own self-definition …The group keeps its distance from the enemy but also needs its presence.

Note that Ataöv suggests that differences don’t cause conflicts; conflicts create differences. Members of a group seize on differences in order to affirm their own identity. A feedback loop ensues: differences are invented or enlarged, which stimulates further animosity, which magnifies differences, and so on.

Twenty or so years before, the social psychologist Henri Tajfel had reached a similar conclusion from another direction. In the laboratory, he sorted respondents into groups, while letting them know that the sorting was entirely arbitrary. When he gave them tasks, like allocating money to other participants, they automatically favoured members of their own group. Tajfel went on to theorise that groups help us to “maximise positive distinctiveness”. They tell us who we are by making us feel distinctive, and they make us feel good about ourselves. When members of a group sense their distinctiveness being undermined, they react by exaggerating differences. Hence: “groups will tend to work harder at establishing their distinctiveness from the out-groups that are perceived as similar than from those which are seen as dissimilar.” (I’m reminded of something that a friend of mine who had recently become a father of identical twins was told by a child psychologist: that twins sometimes develop bigger differences in personality than non-twin siblings because they have a more pressing need to define themselves.)

In his response to Huntingdon, Türkkaya Ataöv drew on Sigmund Freud’s “narcissism of minor differences” - the idea that morbid self-love can be constructed out of a person’s exaggeration of the differences between herself and those around her. In the context of groups, Freud proposed that the function of this tendency is to increase internal cohesion, by directing aggression externally, towards outsiders. Michael Ignatieff used Freud’s idea to help him comprehend the war in the Balkans, on which he reported. He was struck by how similar the warring groups were:

The Serbs and Croats drive the same cars; they’ve probably worked in the same German factories as gastarbeiters; they long to build exactly the same type of Swiss chalets on the outskirts of town and raise the same vegetables in the same back gardens. Modernisation – to use a big, ugly word – has drawn their styles of life together. They have probably more in common than their peasant grandparents did, especially since their grandparents were believers.

Ignatieff concluded that identity is relational - that a Serb understands his Serbian-ness in opposition to Croatian-ness. He reflected on the way that globalisation can lead to people fetishising local identities. As boundaries between states and peoples dissolve, “we react by insisting ever more assiduously on the margin of difference that remains.”1 The Scottish journalist Alex Massie recently noted that Scottish nationalism is in the ascendant at a time when Scotland and England have never been more alike.

Although this fetishisation can overtake whole communities, it varies within them according to personal disposition. Psychological differences play a big and under-rated role in political divides. There is evidence that political radicalism correlates with high anxiety, which seems to push people towards the security of a rigid political identity. Some folk just get very anxious if they don’t know where the boundary between their group ends and the other begins. They want to be able to say I’m with these guys. And that often means saying, I’m definitely not with those guys standing next to me.

That’s probably why Labour’s internal arguments get so feverish. The far left group does not, for the most part, propose wildly different policies to the centrist group, as its members are fond of pointing out whenever they are accused of extremism. But if all they had to distinguish themselves was a belief in somewhat higher public spending, or somewhat more public ownership, then they wouldn’t get the emotional gratification that comes from having a political identity with a hard border. They need to believe that their political neighbours, centrists with whom they share a party, are corrupt and stupid and just like all the others, in order that they can feel good and wise and special. The dividing line must be marked out brightly, in vitriol.

Maybe I’m letting left-centrists off the hook too easily here. Don’t they also have a psychological investment in group identity? Yes, in the sense that they like to think of themselves as the ones who are calm, rational and analytical; who prefer “pragmatism” to “ideology”; who have a stronger connection to “real people"; who are generally more rounded human beings than those in the group to their left. These assumptions are deeply tenuous and undoubtedly irritating if you’re from the group being condescended to by these smug and bloodless bastards. But I don’t think the relationship is symmetrical.

Centrists tend to be less tightly attached to a political identity - in fact it’s precisely that looseness, more than any ideological or policy position, which defines them. Centrism is a mindset, not a philosophy. To use an example that isn’t directly about party politics, look at the range of responses to Covid-19. There is a group which is very attached to the need for strict restrictions and believes the government isn’t doing enough to protect society from the virus, and there is a group which believes that society should open up and “live with the virus”. If you have moved between these two positions as the situation changes, then you’re a centrist.

You may of course have been completely wrong at both ends. My point is not that centrists are always right, but that they tend to have shallower personal attachments to their positions. Belief doesn’t congeal into selfhood quite so readily, which makes for more cognitive flexibility, and less aggression. Being proved wrong about the path of a pandemic, or the success of a politician from an out-group, doesn’t feel quite so close to a mortal threat.

As a rule, internecine battles are more frequent and more vicious on the left than on the right. Now, I’m sure you can cite counter-examples - after all, it wasn’t long ago that the Tories split over Brexit, although the truth is that the Remainers barely stood a chance. Generally speaking, though, parties of the right tend to be more unified, because they are relatively less interested in carving out unique political identities. They like power too much. If Trump is seen as a winner Republicans will back him wholeheartedly; if not, they won’t. (That’s true of most Democratic primary voters, too, actually, just not of the activists.)

It’s the left, of course, which champions identity politics. Political movements which represent clearly defined causes - feminism, antiracism, LGBT activism, environmental activism, etc - should in theory be highly cohesive. In reality they often splinter into hostile factions and sub-factions, hampering progress. Why is that, and is there a pattern to it? That’s what I want to get into next time.

If you liked this post, please share it and consider signing up to The Ruffian.

Oh and if you liked this post you’ll love my book, CONFLICTED. Click here for links to your favourite booksellers (UK and US).

The rest of this edition is for paid subscribers only. If you’re not a Ruffian already, sign up; if you’re a free subscriber, please consider the paid options. I promise that you will immediately feel different and special.

Beyond the paywall: some of my favourite articles, threads, podcasts and music plus my brief takes on the state of the nation - Johnson and Covid.