The Renaissance Redux

'Notes On the Florentine Renaissance' Free To Read This Time

I posted this a few weeks before visiting Florence. I’m now in Florence, and too stuffed with pasta and ice cream immersed in its history and culture to compose a full dispatch. I hope you’ll accept my apologies, along with this repost, which was partially gated and is now free to read. I’ve added a coda.

I’ve been reading The Florentines: From Dante To Galileo, by Paul Strathern, which is very good. It doesn’t have an eye-catching new angle, innovative structure, or flashy prose style. It just does what it says on the tin, and it does it well, albeit a little stolidly. It starts in the early fourteenth century, with Dante, and takes us, more or less chronologically, through the next two to three hundred years. It tells the story of the Italian Renaissance, with Florence as the beating heart of this artistic and intellectual revolution. Its narrative includes the city’s economic and political vicissitudes. We learn about Dante, Botticelli, Da Vinci, Machiavelli, Michelangelo, Galileo; we also learn about the Medici and Savonarola. I recommend reading The Florentines. In the meantime, here are some bits I found particularly interesting:

Dante was born in 1265, some time in May, making him a Gemini. I mention this because just about everybody from the period believed in astrology, from Dante to Aquinas to, much later, Galileo. Even though it was superstition, astrology did contain intellectual protein. It was a vehicle for self-reflection and analysis, and thus a forerunner of modern psychology. It was also a field in which mathematics was developed, particularly trigonometry and algebra.

Florence was one of the five big city-states in the Italian peninsula, the others being Milan, Venice, Rome, and Naples. All were engaged in a complex and ever-shifting game of thrones which included the Pope in Rome. The cities had to contend with interventions from France and Spain. Florence’s power grew in tandem with its economic growth, which was based on wool and banking. The city was in theory a democratic republic although in practice it was usually run as a kind of benign autocracy.

Florence was riven by conflict between the Ghibellines - roughly, aristocratic families who were loyal to, and dependent on, the Holy Roman Emperor - and the Guelfs: merchants, workers, and shopkeepers: the popolo (‘the people’).

Dante had an insanely intense, lifelong infatuation with Beatrice, a girl he first met when they were both nine years old. It’s not clear if this love was reciprocated and it doesn’t seem to have been consummated. Beatrice married someone else and died at the age of 24. She remained Dante’s muse. In the meantime he had four children with his wife, Gemma. It was not a happy marriage. Everyone knew he loved Beatrice.

Dante was part of a scene of hipster poets, including Bocaccio and Petrarch, who revered the literature and thought of ancient Rome. Eventually Florence would become one big multi-artistic scene, but Dante’s scene was the first.

Dante was heavily involved in Florentine politics. The Guelfs split into two factions, pro-Pope and Pope-sceptical. Dante was on the latter side, which lost out. He was exiled from his Florence and never allowed back. The Comedy is haunted by longing for Florence, and for Beatrice. It’s also coloured by hatred for Dante’s enemies: the Pope, Ghibelline leaders, the Holy Roman Emperor, rival poets.

Strathern cheats a little, though it’s worth it, to tell us about Leonardo Fibonacci, from nearby Pisa. Fibonacci was from the preceding generation-but-one to Dante (he died around 1250). Quite apart from his famous sequence, Fibonacci transformed European mathematics and thus so much else. Fibonacci and his father were traders who travelled far and wide, including to Muslim regions in North Africa and the Middle East. At the time, Europeans were using the numerical system they inherited from the Romans, which makes multiplication and division convoluted and effortful. Fibonacci realised that the Arab system made complex calculations much easier, and played a central role in its introduction to Europe. What followed? Science, modern engineering, accounting, banking; in short, a massive jump in the collective IQ of a continent. Surely Fibonacci is underrated as a figure of importance in the history of the West?

By the early fifteenth century, there was growing interest, particularly among young intellectuals, in the art and ideas of ancient Rome and Athens. People were used to the idea of religious pilgrimages to Rome; now they travelled to see the remnants of the old city, previously considered pagan junk: the Pantheon, Colosseum, Forum, surrounding relics.

Strathern tells us about two Florentines, Brunelleschi and Donatello, wandering through the ruins together. They make a sitcom couple: Brunelleschi, 26; short, grumpy, podgy and introverted, and the teenage Donatello, handsome, charismatic, flamboyantly homosexual. Brunelleschi comes back determined to crack the secret of the Pantheon’s dome, and go one further (the Duomo has no hole). Donatello makes painstakingly exact sketches of classical figures. Back in Florence they became long-time collaborators and rivalrous, distrustful friends.

While working on the Duomo and a dozen other architectural and engineering projects, Brunelleschi invents, or at least becomes the first to definitively theorise, the painterly technique of perspective. BOOM, painting is transformed. Paolo Ucello and Piero della Francesca, both learned in maths and geometry, develop Brunelleschi’s technique in ingenious ways, and bend space to their will, making pictures with two or even three different perspectives.

The founder of the Medici dynasty, Giovanni, was a self-made banker who parlayed his wealth into political power. Giovanni was very savvy. In the late 1410s there were no fewer than three claimants to the papacy, each backed by different states. Giovanni becomes the banker to the rank outsider, a former pirate and ne’er-do-well called Baldassare Cosa who somehow gets declared (by France and England) Pope John XXIII. The Council of Constance takes four years to decide who the real Pope is, but Cosa is outmanoeuvred and imprisoned, and a huge ransom is demanded for his release. Everyone is astonished when Giovanni pays it. What a foolish thing to do - to lose money and face over this, well, loser. But Giovanni regarded it as an investment in the Medici brand. From now on, people would know two things about the Medici: first, that they were unwaveringly loyal to their clients. Second, that they had very deep pockets. Within five years, the Medici were appointed bankers to the Pope. They ran the most lucrative, extensive, and prestigious banking network in Europe. They were Goldman Sachs.

Giovanni was friendly with Brunelleschi, to whom he granted one of the city’s first patents (for a paddle boat). Brunelleschi, not a joiner by nature, hated the system of guilds. Guilds maintained pay and standards for various craftsmen, but ran a closed shop and a monopoly on the city’s cultural production. The patent enabled Brunelleschi to operate on his own terms. The introduction of patents proved crucial to Florence’s cultural evolution and to the Renaissance. As the guilds began to lose their grip, opportunities for creative entrepreneurship arose.

Giovanni dies in 1429, aged 69. As well as making the Medici top dogs, he supported Florentine artistic endeavours. This was partly out of genuine admiration for craftsmen, artists, and beautiful buildings, and also a way of rivalling the soft power of Rome, which had the glamour of the papacy. Giovanni handed over the reins to his twenty-something son Cosimo, who proved to be a capable steward of the Medici empire, and an even keener cultural patron. It’s under Cosimo, in the mid-fifteenth century, that the Florentine Renaissance reached its full flowering.

Strathern borrows a lot, as all historians of this period must, from Giorgio Vasari’s Lives of the Artists, written in the sixteenth century. Vasari wasn’t just a chronicler of Italian Renaissance artists, he was one of them, a Florentine painter and architect. He played a vital role in the formation of our modern idea of an artist, as opposed to a craftsman - as someone who didn’t just serve their clients but followed their own muse. His book is full of gossipy observations and insightful advice, like this: “Artists who are strongly drawn to reading will gain the most benefit of their knowledge. This is especially the case with painters, sculptors, and architects. Ideas derived from such studies will inspire their imagination.” If you want to be artist, as opposed to a craftsman, you need to be intellectually curious. Similarly, if you want to be a good artist, you need to know your craft: “When theory and practice are well-wedded they will produce fruitful art - for skill is thus enabled by learning, which draws it to perfection.”

In 1439, Cosimo pulled off a diplomatic masterstroke with far-reaching consequences for the Renaissance. The Byzantine Emperor, feeling heat from the Ottoman Turks, had appealed to Pope Eugenius IV for aid. The Pope, in turn, suggested a reconciliation between the Eastern and Western churches. They agreed to hold a council in Ferrara, a city in northern Italy. But when the plague threatened Ferrara, Cosimo saw an opportunity. In a shrewd deployment of largesse he offered to host the council in Florence, and to cover everyone's expenses. He made Florence the centre of the world.

Over the next few years, as the delegates debated the precise nature of the Holy Ghost, Florence became infused with ancient Greek philosophy, thanks in part to the presence of Gemistos Plethon, a Greek Orthodox philosopher, now in his eighties. Cosimo and other Florentine intellectuals were in awe of this man, who seemed almost old enough to have known Plato personally. They were captivated by his direct knowledge of Plato's work, which they had previously encountered only through Roman interpretations and commentaries. It blew their minds. The world we perceive is just a play of shadows and light on a wall? WTF.

In the 1440s, Cosimo built a new mansion, and commissioned Donatello to make this bronze figure of David, a rather camp giant-slayer. I credit Strathern from not shying away from how gay it is (those boots!). Florence was renowned for having what Strathern calls “a relaxed attitude to homosexuality”. A local proverb: “If you crave joys, fumble some boys”. This was partly to do with the unavailability of females. Having a marriageable daughter who was a virgin was very valuable, and consequently young women were not allowed out much. When they were out, they were chaperoned, surveilled and controlled. So men fell on each other, while dreaming of Ancient Greece. The authorities kept issuing edicts against homosexuality, which they blamed for military defeats. They opened up registered bordellos. But there’s no doubt that the Renaissance was queer. What was marginalised by power became central to culture.

Renaissance artists were fascinated by the challenge of portraying the human body, and also of the mind as revealed in the body. Alberti, one of the Renaissance’s founding fathers, advised artists to study how emotions like anger and sadness manifest themselves in facial expression, posture and movement. There is a psychological depth to Sandro Botticelli’s portrait of St Augustine that was new.

Unlike some of his peers, Botticelli was not very skilled at anatomical verisimilitude. He puts a robe on Augustine partly so he doesn’t have to paint his body. In The Birth of Venus, his most famous painting, Venus’s body is all wrong. Her pose is anatomically impossible. Her neck is too long and bears a strange relationship to the rest of her body. There’s no sense of solidity or perspective. Yet the painting works, not despite of these flaws but because of them. Venus floats impossibly, magically, ethereally; a woman, yes, but not of this world.

The Medici men suffered terribly from gout, an hereditary condition that was probably worsened by their meat-and-booze diet. When Cosimo died, his son Piero became boss. He wasn’t an effective ruler, partly because he was confined to bed. He became known as Piero the Gouty. Not a great title. After Piero’s five-year reign (he died in 1469), his son Lorenzo took over.

Lorenzo, despite being gouty himself, was a paragon of Renaissance manhood: accomplished in sport and music, a decent poet, a great patron of the arts. He was intellectually curious, charismatic and shrewd. He ruled for over twenty years and was known as Lorenzo the Magnificent. Better.

Subscribed

Leonardo Da Vinci rose to prominence under Lorenzo. Da Vinci was a self-invented man. He came from a humble background, born illegitimate, a country bumpkin, with little education and no Latin. He was raised largely by his mother (his father, a notary, had little to do with him). He spent a lot his childhood alone, roaming the Tuscan countryside. You can see why he’s a kind of Montessori dream role-model - his learning in these early years was all self-directed. Aged 14 he somehow got a job as an apprentice to Verrochio, who had mentored Botticelli. He became expert in oil painting and sculpture, and later, philosophy, maths, poetry, engineering…

Leonardo was shy, socially reticent, self-conscious about his country accent. Perhaps to compensate, he adopted a flamboyant, peacocky style of dress. There’s something of Warhol about him. He knew he was different (a feeling that his homosexuality contributed to) and he knew he was special.

In his notebooks, he wrote long descriptions of foreign voyages which he almost certainly didn’t take. They’re full of drama and peril and fantasy, like the time he was swallowed by a giant.

Da Vinci had trouble with finishing. He would get bored with a project, or frustrated by his patron’s demands, or frustrated with himself. According to Vasari: “His intelligence of art made him take on many projects but never finish any of them, for it seemed to him that the hand would never achieve the required perfection.”

One of the paintings he didn’t finish - well, according to Vasari, anyway - was the Mona Lisa. Everything about the Mona Lisa is enigmatic, including its shade of dusk. Strathern illuminates it with a beautifully tender sentence from Da Vinci’s Treatise On Painting: “In the streets, when night is falling, in bad weather, observe what delicacy and grace appear in the faces of men and women.”

Lorenzo sent Botticelli to Rome to paint for the Pope, which enraged Da Vinci (who really did know how to do anatomy). So when Lorenzo sends Da Vinci to Milan, to work for the Duke, Da Vinci petulantly decides he won’t do art at all but become a military engineer. In a letter, he promises Milan’s ruler that he has created all kinds of secret weapons, even though, like a startup founder seeking early-stage investment, his designs were very much at the conceptual stage. As his biographer Charles Nicholl puts it, “It is the pitch of a multi-talented dreamer who will fill in the details later.” Of course, Da Vinci will also do some painting for the Duke, including The Last Supper.

By the late fifteenth century, Florence was the most exciting and glorious city in Italy, perhaps the world, the capital of beauty and truth. Lorenzo laid on the most magnificent pageants. If you were rich, it was heaven to be alive. But trouble was in store.

Among the popolo there was a growing sense of discontent. They didn’t give a crap about Plato or the science of perspective. They wanted to feed their families and that was getting increasingly hard, due to a slump in the wool industry (caused by competition from England and the Low Countries). Amidst the resulting discontent and turmoil arose the extraordinary figure of Savonarola, a Dominican friar and populist avant la lettre.

The poor flocked to Savonarola’s sermons, in which he denounced the city’s rich rulers and corrupt clerics. At the pulpit he was intense, a shouter and a screamer, but otherwise he was savvy and calculating. He quickly became a big player in the city’s politics by presenting himself as the ‘little Friar’, an incorruptible man who spoke truth to power. Whoever he was with, he dressed in a shabby robe and sandals. (The High Sparrow was based on him).

Lorenzo, now on his death bed, realised he had to deal with this turbulent priest. He decided to try and obtain his official approval in a face-to-face meeting. He succeeded but died the day after, to be replaced by his less shrewd son, another Piero.

The Medici bank had run out of money. After caving to the demands of the King of France in a humiliating settlement, Piero was forced into exile, and Medici rule collapsed. The city’s power brokers now had to acknowledge that the only figure capable of keeping the city together was Savonarola. They sent him to negotiate with the French king, whose troops now occupied the city and threatened to sack it. Charles VIII fell for the little Friar’s charismatic authority: when Savonarola told him to turn around or face the wrath of God, he turned around and took his troops with him.

Savonarola now imposed his fundamentalist, puritanical religious ideology on Florence, assisted by bands of young men - ‘Savonarola’s Boys’ - who bullied women in the street they deemed to be wearing morally inappropriate clothes (sound familiar?). In 1497 Savonarola ordered the collection of all items of luxury in the city. ‘Luxury’ items included paintings, ancient philosophical manuscripts, musical instruments. They were piled up high in the Piazza della Signoria and set alight in what became known as “the bonfire of the vanities”.

By 1498, the popolo had wearied of Savonarola, who banned gambling and prostitution but didn’t deliver the economic benefits he promised. The Pope had excommunicated him. With his authority in tatters and no powerful supporters, the Florentine authorities decided they’d had enough. Following a trial, he was found guilty of heresy and sedition. The Little Friar was hanged and burnt at the stake, in the Piazza della Signoria.

One of the attendees at Savonarola’s sermons was Niccolo Machiavelli, a young civil servant, who sent a cool analysis of their rhetorical structure to the Florentine ambassador to Rome. Machiavelli gained a reputation as a skilled diplomat, leading a mission to the court of Louis XII in France. He was analysing everyone he encountered. In his letters and memos, he would try and identify and articulate the underlying principles of power he saw in play, with historical analogies. He was very much a product of the Renaissance, seeking a scientific grounding for politics.

As a young artist, Michelangelo used to practice sculpture in a park near the San Marco monastery, where he would overhear Savonarola preaching to fellow friars in the monastery garden. He was enthralled. Sixty years later, he told a friend he could still hear Savonarola’s voice ringing in his ears. Botticelli, who was much older, fell for Savonarola to such an extent that he repudiated his own art. Michelangelo, despite being profoundly religious, never did that. For him, art and religion were inextricable.

Lorenzo set up a school for sculptors. Michelangelo, an apprentice, got a place after his master recommended him. He was talent-spotted by Lorenzo, who invited him to live and work at the Medici palazzo. There, he got to learn from philosophers and poets as well as artists. Members of the court were more or less openly homosexual, which Michelangelo found difficult; he was homosexual himself but ashamed of it. For his all of his long life Michelangelo’s art was forged from the conflict between his spiritual and sensual yearnings.

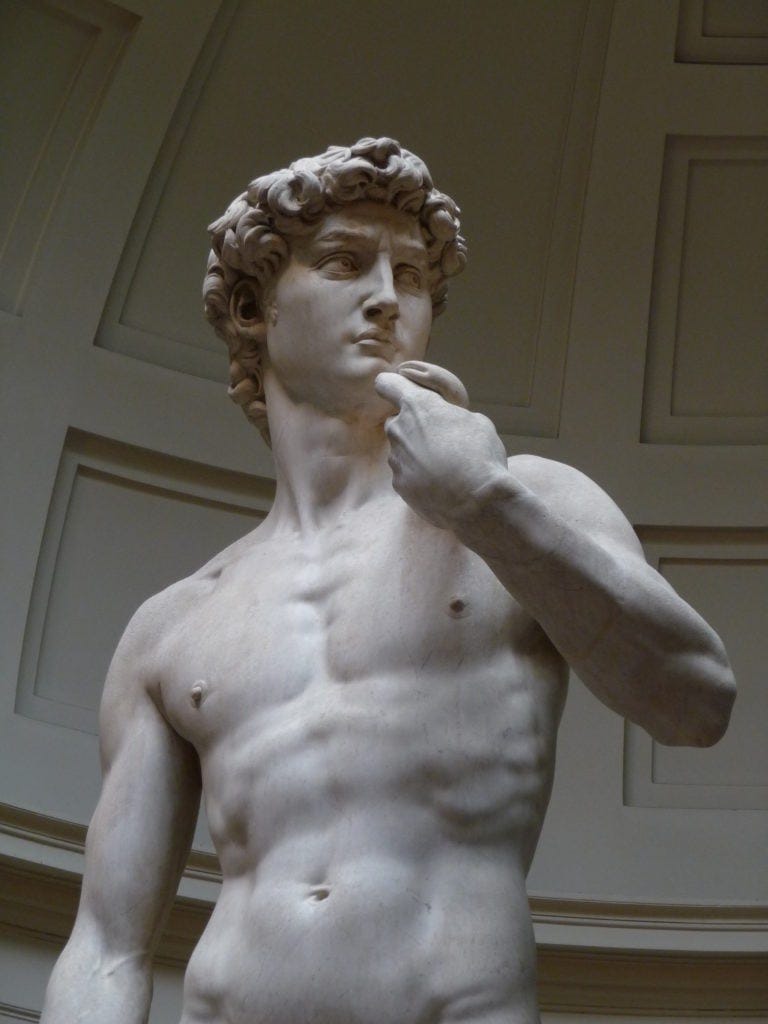

After Lorenzo’s death (which devastated Michelangelo) the city commissioned him to make a statue of David. He was given a warehouse near the cathedral and an eighteen-foot high block of forty-year-old marble (therefore dry and difficult to carve) that had been mutilated by dunderhead sculptors. Michelangelo set to work on this inadequate material. He worked obsessively for three years, sweaty in the summer, stiff-fingered in the winter. The statue he made is both a celebration of what it is to be human, in an ideal, Platonic sense, and a deeply sexy, sensuous man. Fair to say that Michelangelo had different taste in men to Donatello:

Michelangelo got the Sistine Chapel job after being recommended for it by his enemy. Donato Bramante, architect of St Peter’s Basilica, was jealous of this celebrated young buck, and keen to to divert him from building the tomb of Pope Julius II, a job that Bramante coveted. He suspected that Michelangelo didn’t have much experience in painting (true, at least compared to sculpture) and expected that the task of painting a vast ceiling would finally discredit him. Michelangelo understood what was going on and was very reluctant to take the job, but the Pope insisted.

At which point, Michelangelo goes into full beast/genius mode and says right, you fuckers, I’m going to make the greatest thing ever. He proposes a much more ambitious plan than the one the Pope suggested - 300 figures instead of 12 - and sets to work. It takes him four years of very demanding physical and intellectual work, standing on a scaffold, neck bent, squinting at his work without being able to step back from it. By the end of it he has turned Bramante’s poisoned chalice into an elixir.

The last of Strathern’s profiles is of Galileo Galilei, who comes from a later period than most of the others he covers. Galileo was born in 1564 (same year as Shakespeare, fact fiends). The chapter is a decent primer on GG, although Strathern has less to say about him than the artists. I learnt that GG’s father Vincenzo was a prominent musician and composer (which perhaps accounts for GG’s wonderfully assonant name). Vincenzo was a stubborn and combative character who hated being told what to do. I guess the apple didn’t fall far from the tree - wait, isn’t that Newton?

Strathern doesn’t press too hard on any one argument but if there’s a theme I take away from The Florentines it’s the importance of conflict to the Renaissance. Spiritual conflict, between religion and art, morality and sensuality; military conflict, which drove so many of the innovations in engineering and science; social conflict, between Ghibellines and Guelfs; Italian conflict, with the Medici striving to make Florence the greatest city in Italy. Then, of course, there was all that artistic and intellectual conflict: lots of brilliant and entrepreneurial artists with massive egoes, packed into the same city, all trying to outdo each other: an exceptionally productive culture war.

If you enjoyed this, please share it! And if you’re not a subscriber yet, do sign up:

Coda (From Florence)

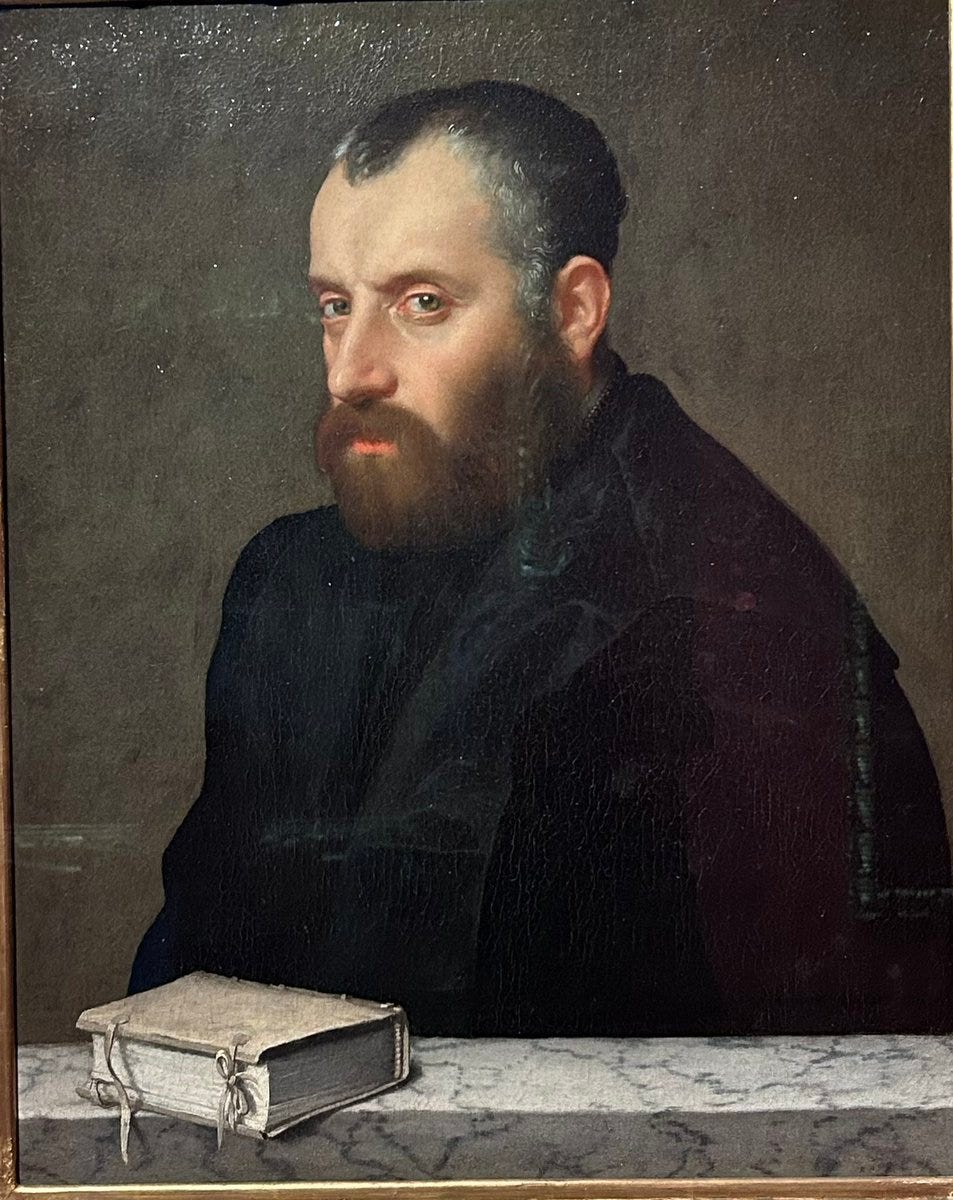

The Ufizzi, despite being, inevitably, over-crowded - full of people who toddle into a room, hold their phone up in front of the paintings, and toddle blindly off again - is worth it. There is so much good stuff that some of it you can view with nobody around, just because it’s not in one of the big rooms. I found myself face to face with Rembrandt, just me and him, pursing our lips over the barbarism of tourists. My favourite of the overlooked paintings was this incredible Moroni from the mid-1550s.

It’s a portrait of a particular person (unknown) and also of a Renaissance type - the introverted intellectual bent on the cultivation of his mind. The book is half-untied, which implies that it subject has been interrupted in the act of reading. Basically, he can’t wait to get this stupid sitting over with so that he can get back to his book. Note the red raw eyes. Hard to tell in reproduction but the book juts out of the frame, virtually insisting on its own importance.

Oh and I can add another book to your list, one that I picked up here in Florence. Mary McCarthy’s The Stones Of Florence (1963) is a complement and contrast to Strathern: more stylish, speculative, and playful. McCarthy is always the boss of her material, never for a moment weighed down or intimidated by it. The Stones of Florence is as pleasurable as the city. Speaking of which, I’m off out for a Negroni, so I’ll leave you with a sample of McCarthy:

Since the ancient Greeks, no people had been as speculative as the Florentines, and the price of this speculation was heavy. Continual experiments in politics had caused a breakdown of government, as in Athens, and artistic experiment had begun to unhinge the artists. ‘Ah, Paolo [Ucello],’ Donatello is supposed to have remonstrated, ‘this perspective of yours is making you abandon the certain for the uncertain.’ The advances in knowledge gave rise to an increase in doubt. By a cunning legerdemain, it was found, a flat surface could be made to appear round; at the same time, paradoxically, the earth itself, which appears to be flat, was being shown to be round by scientific argument. The whole relation between appearance and reality was unsettled. ‘Doubting Thomas’, usually shown (by the Venetians, for instance) as a middle-aged person, became for the Florentines a beautiful, entrancing youth - the most charming of all the disciples, as he sits with his lovely chin tilted back on his hand in Andres del Castagno’s ‘Last Supper’ or as he stands, with graceful curls, and his fair, sandalled foot extended in Verrocchio’s sculpture on Orsanmichele.

The brain refreshes. And the best thing about this delightful post: not one word about Trump. Hooray!

Recommend the Rembrandt in Kenwood House. Noone else there as you take in the master!