Why Does Being Left-Wing Make You Unhappy?

The Ideological Well-Being Gap

Catch-up service:

How Silicon Valley Hacked Behaviour

Can You Imitate a Genius?

On London’s Empty Penguin Pool

Am I Anti-Woke?

Note: this edition is a little too long for email apparently, so you might want to read online by clicking on the title above (or the link at the bottom).

There is currently much concern over an apparent deterioration in the mental health of young people, over the last twelve years or so. The debate has focused on technology. Even if the phones are to blame, however, they’re probably not the only cause. It’s worth noting that the rising prominence of “social justice” discourse, sometimes referred to as the Great Awokening, has taken place over the same period. Excuse my crude proxy:

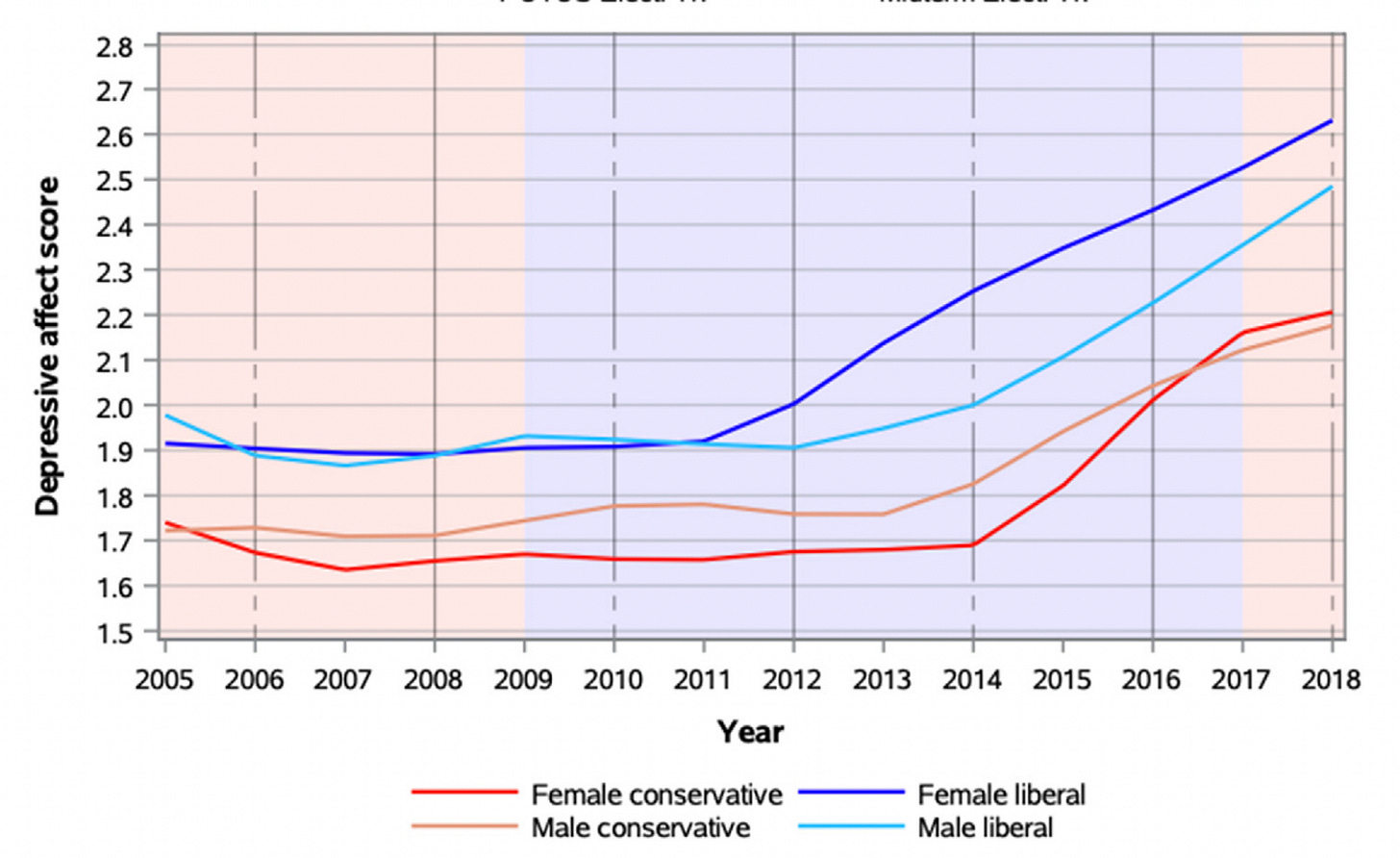

There is indeed some evidence that this is part of the problem. A 2021 paper from epidemiologists at Columbia University, entitled “The Politics of Depression”, proposes that one cause of the rise in youth depression is “increasing exposure to politicized events”. Importantly, the authors observe a significant difference in rates of depression between students who identify as liberal and conservative:

This is consistent with a longstanding finding in the scientific literature on happiness: people who lean right, politically speaking, tend to be happier than those who lean left. For instance, this analysis of two long-running global happiness studies finds that conservatives are generally happier than liberals, with the relationship reversed in only five out of ninety-two countries. Another study, of sixteen European countries, finds that voters who espouse conservative beliefs report greater happiness than liberals, even as more liberal countries tend to be happier overall.

Note: I’m using the terms “liberal” and “conservative” to denote left-leaning and right-leaning, while acknowledging that they’re imprecise. I’m also using a lot of American data simply because that’s where the bulk of this research has been carried out, although the basic finding does seem to be replicated globally.

The ideological gap in well-being precedes contemporary concerns about phones and polarisation and culture wars, and it’s not confined to young people. As Musa al-Gharbi notes in his recent, comprehensive evidence review, “the gap manifests clearly across all age groups and is present as far back as the polling goes.” Liberals have worse mental health than conservatives. As well as being more likely to be depressed, they tend to be more neurotic and more anxious. This is true across genders and age groups.

What causes this gap? Al-Gharbi outlines competing hypotheses. Conservatives tend to be more religious, more patriotic, and more married, and all these things correlate with happiness. Indeed, it has been argued that political conservatism is not the important variable here - that liberals who feel deeply connected to country and religion and family would be equally happy. I’m not sure if this is a real distinction, since those liberals would be behaving in ‘conservative’ ways even if they espouse liberal beliefs, but anyway, church-going conservatives tend to have better mental health than church-going liberals, so it seems that conservatism does provide benefits independent of religiosity.

Another theory is that conservatives are people who enjoy inherited advantages. They tend to have had healthier childhoods and be more physically attractive (I know, really?) and therefore want to conserve a social system which favours them. But this theory is difficult to square with a trend that al-Gharbi has been tracking in the U.S. and elsewhere, of richer people increasingly identifying with liberal views. As he puts it, “the ‘winners’ in the current economy are increasingly the people who are most depressed. This is hard to explain if the happiness gap is purely a function of privilege.” It’s also the case that immigrants and minorities in the US are more likely to be socially conservative than whites (at least somewhat true in the UK too).

It’s not clear from evidence if people who are genetically or socially predisposed to anxiety and depression are more likely to be liberal, or if there is something about liberalism that makes people depressed. But al-Gharbi makes a good case that liberalism exacerbates depression and anxiety, and that this partially explains rising levels of mental distress over the last ten years.

Liberals are much more likely than conservatives to seek diagnosis for moderate or low mental health symptoms. We might think that conservatives are just in denial, too proud to seek help, but conservatives with severe mental health symptoms are as or more likely to pursue professional assistance. Liberals not only tend to be more emotionally unstable, they also value emotionality more than conservatives - they like to dwell on emotions, to talk about them, to expound on trauma and pain. Studies find that they are more upset than others by public tragedies, like school shootings, or catastrophes like Covid-19, and that their distress lasts for longer.

By presenting these findings, I don’t mean to suggest that the ideological well-being gap implies everyone should be more conservative. First of all, what makes one happy or not is a rather narrow way to think about one’s political beliefs, and even on those terms, it wouldn’t make sense for everyone to be conservative, given that more liberal countries tend to be happier and you don’t get more liberal polities without liberal politicians and activists. Second, you can plausibly argue, as liberals often do, that unhappiness or at least deep dissatisfaction is a rational response to reality - to climate change, inequality and injustice, and so on.

But I do think that, in its more extreme form, the liberal mindset is unhealthy and self-harming. The last ten years have seen the emergence of a more performative and pathological strain of liberalism among some highly-educated young liberals, who unwittingly practice what Jonathan Haidt calls reverse CBT (cognitive behavioural therapy). CBT teaches patients to recognise that their own worrying and catastrophising and knee-jerk pessimism are the causes of distress. In order to get happier, they need to break with those mental patterns. Modern liberalism teaches people the opposite - that such patterns are signs of moral virtue. Social media pushes liberals together with others who think in the same way, and throws reputation and status into the mix: the more you worry, and the more dramatic you are about it, the more admirable and attention-worthy you become. In this game, to be content is to lose - is to be nobody.

If I had to name a single cause of the well-being gap, I’d say it’s that liberals are more political than conservatives. They think more about politics, care more about it, spend more time reading about and discussing it. Not just party politics, but the politics of gender, race, sexuality and so on. And that can get you down.

Modern liberals, or progressives, take grim satisfaction in asserting the inescapability of politics. One of their favourite turns of phrase is “But X is inherently political” - i.e. that activity or human behaviour that you fondly imagined to be unsullied by the machinations of power is, in fact, governed by them. Friendship is political. Science is political. Journalistic objectivity is political. Fiction is political. Music is political. Food is political. Love is political.

While there is usually some truth to “X is political”, it can also be a glib rhetorical move which leaves out more than it says (as Stuart Ritchie argues with regard to science, here) and it fails to acknowledge that we value these things precisely because they’re anti-political. There’s an element of status display in pushing politics into everything: the implication is usually that anyone who doesn’t agree is either complicit in oppression or, worse, naive and unsophisticated.

Most pertinently, for our purposes, it’s bleak. For a certain kind of progressive, anything that might seem above or beyond politics - a commitment to objective truth, a love of music or food or sport - is just politics by other means, part of the relentless battle of tribe versus tribe, identity versus identity. That’s pretty depressing, especially if you sincerely believe it. A flamboyant refusal to take joy or succour or pride in anything manifests in scathing denunciations of Friends (sitcoms are inherently political) and curatorial captions to great paintings that focus on slavery and colonisation even when the paintings have nothing to do with either.1 That show you liked? Racist. That art you love? Oppressive. Your country? Evil. Suck it up.

At the same time it is for some reason necessary to insist that it’s the other side who engages in ‘culture war’. Progressives have become like Putin insisting that Ukraine forced Russia to invade it. An obsessive attention to what divides us is accompanied by constant talk of kindness, inclusion, diversity. This is society as office politics; passive-aggression at scale. It’s telling that the word “microaggression” emerged from universities. Academics, notoriously sensitive to status slights, have somehow succeeded in exporting their experience of the workplace - one in which everyone is always trying to undermine each other in subtle ways - to the rest of us.

When everything is politics, we don’t speak of friends or citizens or people, we speak of allies. The term is symptomatic of this Game Of Thrones-without-the-slaughter worldview, in which everyone has to seek safety from attack in provisional, shifting coalitions of necessity. You can also see this hyper-political mindset in the way that progressives debate online, where they often seem less concerned with establishing what is true or reasonable than with the tactical implications of a position. If you’re making a case, for, say, the rights of women to women-only spaces, you will be dismissed on the basis that the wrong people agree with you. The fundamental question seems to be not “what is true” but “where to stand” or who to stand with.

You might say that just as conservatives find meaning in family or religion, liberals find meaning through activism and political discourse. But these different kinds of social participation do not have equal payoffs in well-being. The evidence suggests that going to church or spending time with loved ones tends to be good for people, whereas a preoccupation with politics is bad for your mental health. As we’ve seen, people who follow the news closely tend to be unhappier. Politics can be corrosive to friendships. Liberals are more willing to break with friends over political differences. Politics is divisive by nature, and the acidic effect that it has on relationships is particularly harmful, since for most people, human relationships form the infrastructure of happiness.

It is hardly surprising that white liberals are suffering from worse mental health. They see their own class as complicit in oppression. They are increasingly anxious about “interactions across difference” and put a great deal of conscious thought into adapting their behaviour to the demographic characteristics of whoever they’re talking to. They second-guess themselves, scrutinise their own motivations and behaviours, dwell on awkward moments, ruminate on how they came across. This kind of behaviour, so ruthlessly satirised in Curb Your Enthusiasm, is associated with anxiety and depression.

You could argue that white liberals are nobly taking a hit to their happiness so that others might flourish, but suspicion and anxiety have a habit of spreading and ramifying. Al-Gharbi observes, “there are reasons to suspect that certain strains of liberal ideology may exert uniquely pernicious effects among women and people of color.” If women and minorities are encouraged to interpret ambiguous situations in the most uncharitable way possible - as racism, misogyny, homophobia, conflicts in a zero-sum power game - then liberals will “undermine the well-being of the very populations they are supposed to help.”

Of course, conservatives aren’t immune to the over-politicisation of everything. In the US in particular they’re increasingly prone to see everyone in public life, including and especially those working for government institutions, as participants in a grand conspiracy against them. That’s deeply unhealthy too.

The political dimension of our existence is important. It’s crucial to be aware of how, in every walk of life, the strong are prone to exploit the weak. But whenever we can, we should keep politics in its place, lest it becomes a distorting lens. Most people, most of the time, aren’t trying to dominate or undermine or judge you, and they don’t assume you want to do so to them. They just want to get something done, or to help out, or to share a moment of laughter or pleasure or wonder. Any politics which doesn’t recognise its own limits will generate misery.

After the jump, a jam-packed Rattle Bag, including first thoughts on the Cass Review; Hannah Arendt on friendship; a classic post on the future of AI; how design instils virtue; one great podcast and one great TV show; a British education scammer doing well in America; and seven minutes of pure soul-nourishing beauty.

The Ruffian depends entirely on paid subscriptions, so if you haven’t taken one yet, please consider it. You can also hire me to give talks on curiosity, productive disagreement, being human in the age of AI, or other topics, including politics, if we must.