Is Forgiveness a Power Move?

Plus a very juicy rattle bag which includes my favourite ever sad song

Catch-up service:

20 Observations On Friendship

Weird Should Not Be an Insult

Nike’s Winning Strategy

The Trump Shooting Was Fake News

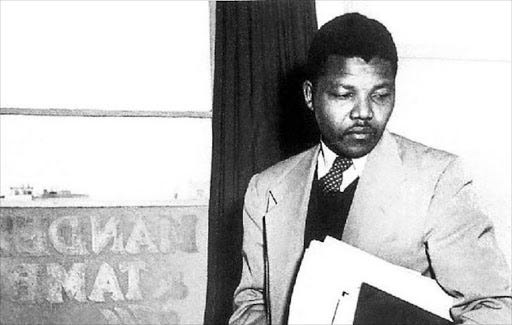

I’m currently reading Winnie & Nelson by Jonny Steinberg. I don’t know if the title subconsciously reminded me of my own book, which I’m finishing as we speak, but either way I’m very glad I picked it up because it’s superb: a penetrating portrait of the Mandelas, and a terrific way to learn about the history of modern South Africa. I may write more on Winnie & Nelson; for now I want to discuss a story from it.

When Nelson Mandela was a young man, in the 1940s, he took a part-time law course at Wits University in Johannesburg. Having left his tribal homeland behind, he threw himself into a legal career, and at the same time into politics. Doing so required extraordinary willpower, and a remarkable capacity for self-invention.

This was not a well-trodden path. Mandela was the only African law student at Wits. As soon as he started, his professor encouraged him to go elsewhere, on the basis that the study of law was not for black men. Mandela did not have money and relied on his first wife’s income while studying. He went deeply into debt. He lived miles from the university in a small house with no electricity; by night he studied, exhausted, under the light of a paraffin lamp.

He had chosen a life in which he would be made painfully aware that he was a second-class citizen every day. Black students at Wits were permitted to study in the same lecture theatres as whites but not to use the university swimming pool or to attend formal social events. Many of Mandela’s fellow students studiously ignored him. Even the supposedly progressive ones, who conversed with him amicably in private, shunned him or became notably ill-at-ease with him in public. A fiercely proud man, raised in his homeland as an aristocrat, Mandela suffered these daily humiliations with forbearance, though he did not forget them.

One example was observed by Jules Browde, a young Jewish military veteran, now a Wits student, who later told this story. In 1946, Mandela’s fourth year at Wits, Browde was sat waiting for class to begin when Mandela came in. Everyone in the room was looking at Mandela, the sole black student, as he searched for a seat. Eventually, he spotted an empty chair next to Browde and sat down. As he did so, a student sitting just across from them made a great show of getting up and taking a seat somewhere else. Nobody said anything. Browde befriended Mandela after the class, although they did not mention the incident. They stayed in touch, sporadically, over the years to come.

Nearly half a century later, when Mandela was president of South Africa, he hosted a formal lunch for several hundred people. Browde was invited. At some point, Mandela spotted Browde and called him over for a chat. He asked Browde to arrange a class reunion. ‘And Jules,’ he said, ‘Do you remember, when I came into the class…and sat down, the man next to me got up and went and sat on the other side of the table?’ Browde remembered it well. The man’s name, he told Mandela, was Ballie de Klerk.

‘Please see that you ask him to come,’ Nelson said.

When Browde asked why, Mandela said that he wanted to remind him of what he had done all those years ago. ‘I don’t mind whether he says he remembers or he doesn’t remember. Because I want to take his hand,’ - at this point he took and held Browde’s hands - ‘And I want to say, “I remember. But I forgive you. Now let’s see what we can do together for the good of this country.”’

As it turned out, there was a Wits reunion, but De Klerk did not attend, for he had passed away. On the face of it, this story exemplifies Mandela’s famous magnanimity; the way that he extended compassion even to his enemies. But Steinberg, the author of Winnie & Nelson, consistently probes beneath the superficial, and he draws a different moral: