Last of the Curmudgeons

Catch-up service:

My Book Of the Year

Why Are Americans Growing Less Comfortable With Speaking Up?

Is Forgiveness a Power Move?

20 Observations On Friendship

The Slow Horses fans among you already know that a new series has started on Apple TV. Those of you who haven’t watched it: if you do, I pretty much guarantee you’ll become a fan. It’s the most easy-to-like TV show there is. In the age of prestige TV, the shows which get critical attention tend to explore meaty themes: politics, drug addiction, dystopias. Some of them are very rewarding. But there should also be room for shows that ask nothing of the viewer except that they enjoy themselves. It’s just TV, after all. That’s what Slow Horses is: clever, fast, funny, preposterously fun. Pop, not rock. That is not to denigrate its quality; quite the opposite. It takes profound skill to produce such a consistently satisfying confection.

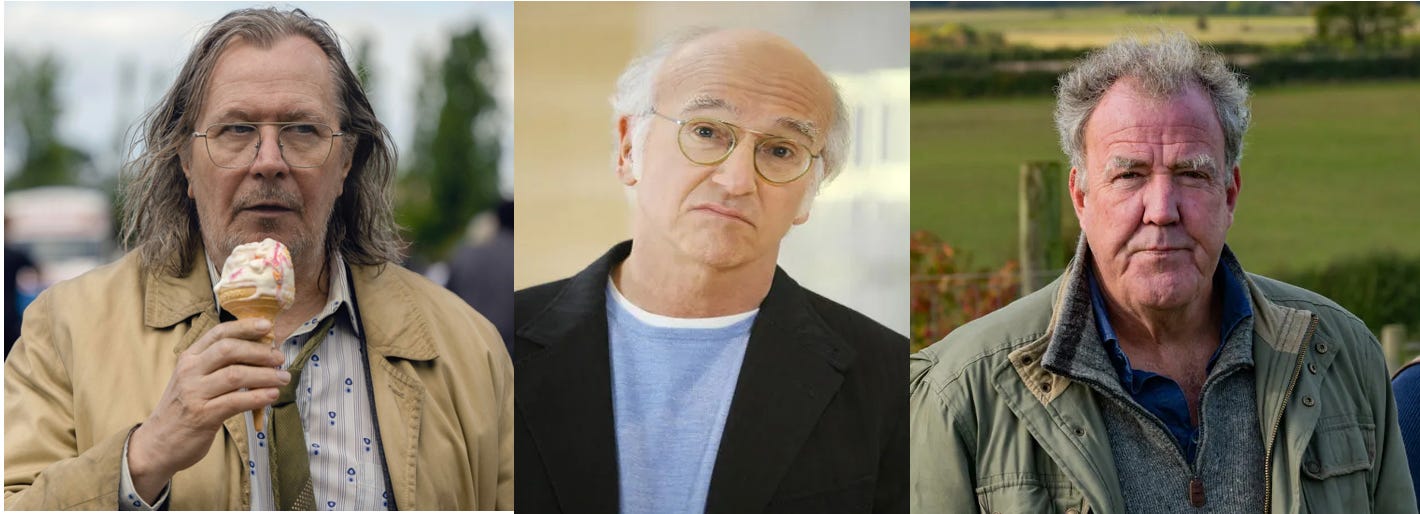

At the centre of the show is the character of Jackson Lamb, as performed by Gary Oldman. Lamb is an ageing MI5 spy who fell out of favour with his bosses and now runs a small sub-office of eccentric agents who have also been frozen out without being sacked. ‘Slough House’ operates as a kind of purgatory for these misfits. They spend most of their days pushing paper at Lamb’s behest. Yet whenever MI5 faces a crisis, the slow horses, led by Lamb, end up saving the day.

Lamb is the kind of physical specimen who doesn’t exist in the world of Succession or White Lotus: long greasy hair, pasty skin, a belly that precedes him into the room. He smokes and drinks and naps at his desk. He farts loudly, sometimes strategically. He is gleefully abusive to his staff, keen to let them know they’re losers who can’t get a job anywhere else. “Bringing you up to speed is like trying to explain Norway to a dog,” he tells one. After meeting Lamb, a smart young MI5 officer asks him, “So you’re in charge of the rejects?”

“They don’t like being called that.”

“What do you call them?”

“The rejects.”

(This exchange is typical of the show’s aerodynamic dialogue). Jackson Lamb is awful, and yet he is, somehow, awfully likeable. In every situation, we want him to come out on top, and he always does; as with that very different character, Jack Reacher, a big part of this show’s satisfaction is the invincibility of its hero. Why do we root for him? Partly because we admire competence, whatever guise it comes in, and partly because even when he wins, he never pretends to be anything but a loser. But it’s also because of Lamb’s refusal to conform to the mimsy niceties of the twenty-first century workplace, with its injunctions to be (or be seen to be) supportive, inclusive, sensitive, kind. In a word, hygienic.

Lamb puts problem-solving - however he cares to define the problem - before everything else, including other people’s feelings. There’s something bracing about that, at least from a safe distance. Even if you believe that the boundaries of acceptable workplace behaviour have shifted in the right direction, you can still take pleasure in a character with complete disregard for them. Indeed the pleasure is all the greater for being illicit.

Jackson Lamb has joined the ranks of the great curmudgeons, a richly peopled character type with a strong British strain. The word has been around since the 1570s, though its origin is unknown. Samuel Johnson, the archetypal curmudgeon, thought it might derive from the French “coeur méchant’ (evil or malicious heart) but modern scholars think this doubtful. The curmudgeon isn’t malicious, anyway, he’s just grumpy, although being grumpy isn’t enough to qualify as a great curmudgeon. The grumpiness must be allied to wit, perspicacity, and purpose. It must have a point.

Apple’s streaming rival, Amazon Prime, also has a curmudgeon at the heart of one of its most successful shows, Clarkson’s Farm. Jeremy Clarkson is not a fictional character but he occupies the same cultural space as Lamb - someone who scorns modern manners. His ascendance to the pantheon of curmudgeons is recent. In Top Gear and The Grand Tour, Clarkson’s persona verged on schtick - a politically incorrect hero for the Boomer generation. What makes him so winning in Clarkson’s Farm is that we see how much work he puts into his farm and how much he cares about it. His grumpiness is a kind of energy produced by his struggle with the capricious gods of nature and West Oxfordshire District Council.

Curmudgeonliness is largely the province of men, mainly older men though not exclusively so. I would classify Andy Murray as one of the great curmudgeons. Watching him play, over the course of his career, I always took delight in his determination to look anything like an athlete ‘in flow’. Even when he was playing brilliantly, Murray appeared tremendously pissed off about everything; unhappy by virtue of being on a tennis court. Physically, he wasn’t graceful like Federer, but angular, crabbed, awkward. In press conferences, he was taciturn, verging on surly. His grumpiness was a kind of honesty about his struggle. He was one of the the most talented and driven players of his generation, up against the three most talented and driven players of any generation. That’s enough to piss anyone off.

The curmudgeon has a strong moral code, though he doesn’t necessarily want you to crack it. One of Murray’s finest off-court moments came when he corrected a journalist who forgot about the existence of female tennis players. He did it in curmudgeonly style - un-ostentatiously, slightly moodily. Probably none of his peers would have bothered to intervene like this, but if they had, they would have made more of a fuss. The abrasiveness of curmudgeons is intended to distract you from the fact that they actually care deeply about other people, and about right and wrong. It’s an inversion of superficial workplace etiquette or celebrity spin. Curmudgeons are vice-signallers.

Beneath the teasing of his farmhands and insistence on his own selfishness, Clarkson’s wider mission in his current show is to highlight how hard the farming life can be, a mission with greater moral clarity than making our roads safe for blokes to drive SUVs really fast on. Jackson Lamb’s grumpiness is directed up as well as down: he is an equal opportunities arsehole, who delights in exposing the shallow incompetence of his sharp-suited bosses. He also cares, we sense, about his agents, although the Slow Horses writers are smart enough only to make the faintest hints in that direction.

Curmudgeons tend to be British, perhaps especially Scottish (as well as Murray, I think of Graeme Souness and Alan Hansen). But one of the greatest curmudgeons of modern times has been American. In Curb Your Enthusiasm, Larry David is flamboyantly self-centred. He treats his loved ones as irritating inconveniences. He gets angry at the mildest, unintended provocations. He doesn’t show compassion or kindness. And yet, as well being entertained by him, we like him, because he so clearly can’t wrestle his personality into the shapes demanded of it by social decorum.

That doesn’t make him happy, it makes him mad, and perhaps a little lonely. After he fails to express sadness over his the death of his friend Richard Lewis’s parakeet, Lewis tells him, “there’s a lack of empathy and compassion and sympathy for practically everything in your life.” Larry replies, “There’s a lack of everything.” We like Larry because we recognise in him our own failures, writ large. We also relish the way he exposes the absurdity, the cant of modern manners, but find ourselves grateful it’s him doing so and not us. Larry is honest so that we don’t have to be.

Curb has come to an end. Clarkson and Lamb aren’t going anywhere for now, but I wonder how many new shows will feature grumpy old men, and whether even the most curmudgeonly sportsmen will have their grumpiness media-trained out of them. Liam and Noel Gallagher are born curmudgeons; today’s pop stars are more like Chris Martin, eager to be good. Now, more than ever, we demand heroes who are upbeat, positive, performatively kind. The curmudgeons have been fighting a rearguard action against modern life. The most appropriate, most curmudgeonly conclusion to any battle is defeat.

This piece is free to read so feel free to share. And hit ‘like’ if you liked it; this makes it easier for new readers to discover.

After the jump, a very juicy rattle bag, including my thoughts on the status of US and UK politics; the only report on AI and the future of the economy worth reading; why most Marxists became liberals; a list of useful skills that can be learned quickly; a clip that’s guaranteed to cheer even the grumpiest of curmudgeons, and much more…

If you haven’t tried a paid subscription yet, you’re missing out - now’s the time!