Why Are Some Of Our Most Successful Leaders Mentally Ill?

On Milei, Musk, and Trump

Catch-up service:

The End of Cheap Progressive Signalling

The Bud Light Debacle

Banishing the Inner Critic

Stop Making Sense

How.I Use ChatGPT

How To Love Classical Music

Before we begin, some housekeeping. Exciting housekeeping!

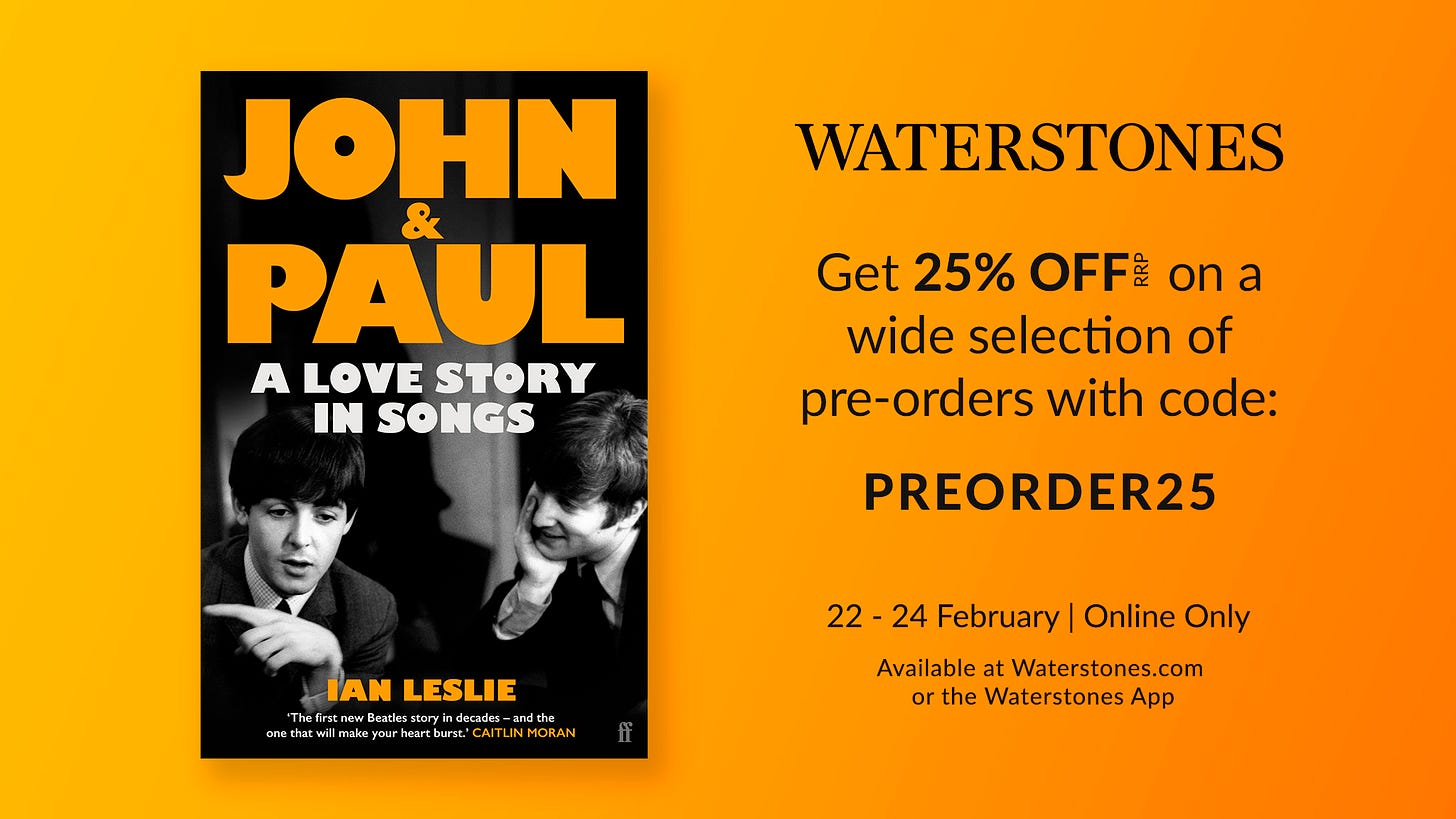

First: if you’re in the UK, you can get 25% off John & Paul if you pre-order from Waterstones this weekend and enter the code below. 25%!

Second: stand by for a new podcast from The Ruffian, dropping tomorrow. It’s an interview with Jemima Kelly from the Financial Times about her encounters with Donald Trump, and it’s absolutely fascinating. Also funny.

Housekeeping over. Carry on.

I recently came across a video of the Argentinian president Javier Milei ranting about “shit leftists” (I think it’s from about a year ago, in the early months of his presidency). It was attached to a viral tweet that reads, “Crazy how Argentina just willingly elected a clearly mentally-ill man as president because inflation was bad.” Here’s the clip:

If you watched this video without knowing anything about Milei you would indeed conclude that he is, if not mentally ill, then disablingly unwell. The torrential invective, wild eyes, contorted mouth, lockdown hair. Those who have followed Milei’s career will know that his demeanour in the video by no means atypical. The Argentines call him desequilibrado - unbalanced. Some of his ‘madness’ may be conscious self-presentation (he has a stylist who precisely calibrates his tonsorial derangement) but it is mostly authentic.

In private and in public, Milei rants uncontrollably about “filthy leftists”, among whose number he includes the Pope. He is unusually obsessed by economics even for an economist; his speeches and interviews consist largely of economic data and argument. He claims to have had a conversation with the ghost of Ayn Rand in a Buenos Aires bookshop. He has four dogs, all named after libertarian economists (‘Milton’ for Milton Friedman). He believes them to have special powers and is said to seek their advice on political strategy. They are all cloned from a fifth dog, his beloved Conan (after the Barbarian), who died in 2017. Milei talks about Conan as if he is alive, and claims to communicate with him telepathically.1

Now here’s the craziest thing of all: Milei has proven to be, not just a surprisingly popular politician, but an exceptionally effective leader, at a time when so many of his global peers seem utterly impotent. He came to power by promising to get a grip on Argentina’s chronic inflation problem, to cut the budget deficit, and to kickstart growth. He said that doing so required drastic, unprecedented measures, the kind of measures no other politician would even consider. He swung a chainsaw around to make his point.

Everyone sensible said he was mad and dangerous. Over a hundred economists signed a public letter warning of the disaster that would befall Argentina if Milei was elected. Yet the Argentines went ahead and made the chainsaw guy president, and for the most part they are glad to have done so. Sixteen months after taking office, Milei has carried out the “shock therapy” he promised, and the patient has responded more or less as he said it would. Inflation, though still high, has nosedived to its lowest rate for five years. The government budget is in surplus. The economy has come out of recession, and growing fast: the IMF predicts 5% growth this year and next year.

Although many Argentines are yet to feel the benefits of these changes, they think he’s going in the right direction; just over a year in, Milei is relatively popular. If the country continues on this new course, Milei will have done what most international observers and probably most Argentinians had come to believe impossible. He will have made the Argentinian economy, a basket case for 25 years, viable again.

Maybe he had to be mad to succeed. Maybe it took a kind of insanity to, first of all, believe he could do it, second, to transmit his conviction to the public, and third, to drive through the high-risk reforms that are enabling it.

The investor-entrepreneur Peter Thiel - whose own sanity is a topic of some debate - once noted that the disproportionate success of autistic founders in Silicon Valley is no accident. Many good ideas seem crazy until they work. Good listeners tend to be too easily convinced that their potentially transformative idea will never take off. Those impervious to social pressure, for whatever neurological or psychological reason, have the tunnel vision required to blast through mountains of scepticism and inertia. Elon Musk is an extreme example. According to his biographer, Walter Isaacson, Musk is probably bipolar as well as autistic, and it’s clear from reading Isaacson’s book that nobody sane would have built either Space X or Tesla into the gargantuan businesses they are, and certainly not both at the same time.

You see similar tendencies among high-achievers in any domain in which new ideas matter, including football management. Pep Guardiola, the most successful manager of all time, and one of the most innovative, shares Milei’s white hot intensity. He was recently filmed blazing away at his goalkeeper after a 2-2 draw, eyes bursting out of his head. Like Milei, he is a monomaniac. A close colleague of his coined the “law of 32 minutes”: the time that Guardiola can talk about another subject before returning to football.

Musk is a Milei fan, as is Donald Trump (Milei has fired about 30,000 government workers and cut the number of ministries from 18 to 9). Like Musk, Milei was bullied by his father, who routinely beat and humiliated him. Like Musk, also, he is thought to have Asperger’s syndrome, finding it hard to relate to other people. His private conversations are said to be impersonal, centring on economics, politics, and dogs. Like Musk, he carries a lot of anger. He first got famous in Argentina after someone mentioned Keynes to him on a TV show, which triggered a foaming tirade. It went viral.

Trump is a political innovator: he flouts all the rules of politics, established over decades, yet he bestrides the political scene. He is “unbalanced”, a ranting obsessive who has been banging on about immigration and tariffs for over forty years. On any question, he makes his mind up quickly and is never swayed by evidence, counter-argument or emotional appeals. Like Musk and Milei, he does not seem to engage with other people as three-dimensional humans but, in his case, as characters in a TV show.

In fact, the crucial attribute shared by Milei, Musk and Trump - along with bottomless energy, idées fixe, and relentless will - is a lack of empathy. (It’s also true, to lesser or greater degrees, of successful leaders from the past, like Thatcher and De Gaulle.) Living in a closed-off mental world is not conducive to good relationships or to happiness, and it’s often a disadvantage in politics (and business). But in certain circumstances, an empathy deficit flips into being a superpower. It turns out that if you don’t care about pleasing people, you can get very popular.

More broadly, madness - or extreme eccentricity, or “neurodivergence” - can be a political strength. The adage that voters prefer candidates with whom they can see themselves having a beer was only true when the electorate liked the drinking establishment. In rigid or unresponsive political systems, the sane and conventional politician seems inadequate. Someone who operates outside established norms can appear erratic or unstable, and even repugnant, and yet be perceived by voters as responding rationally to systemic dysfunction.

In the 1960s, the psychiatrist R.D. Laing argued that insane individuals were operating according to a hidden rationality, adopting strategies forced upon them by repressive and dishonest families. Society was mad, not them. Psychotic individuals often named uncomfortable truths about their families that others were invested in denying. Laing’s theory is now discredited within psychiatry, but in the symbolic world of politics it still resonates. Only the desequilibrado have the audacity and agency to take on an unhealthy, entrenched status quo.

That doesn’t mean, however, that any leader who acts in a crazy way must be on to something. Laing believed that in some cases mental illness helped the individual to make progress, while in others it led only to their fragmentation, and ramifying pain for those around them. Similarly, not all political disruption leads to positive change. There is a tendency among Trump sympathisers to assume that if they can’t see the logic, morality, or sense in what he says or does, then there must be some deeper logic to it that they don’t yet comprehend. But sometimes madness is just madness.

This post is free to read so feel free to share. After the jump, a vintage rattle bag of links, with some really thought-provoking reading (and listening): on UK and European politics, America’s constitutional crisis, trust in personal relationships, and essential content on being human in the age of AI. Honestly there’s so much good stuff here, even more than usual. If you haven’t yet signed up for a paid subscription, give it a go, it’s very straightforward and gets you access to the best of The Ruffian. You’d be crazy not to.