Stop Making Sense

David Lynch, Bob Dylan, and the Beauty of the Inexplicable

Catch-up service:

How.I Use ChatGPT

How To Love Classical Music

Notes On the Great Vibe Shift

The Death of Scenius

Podcast: James Marriott on Neil Postman

How - and Why - To Read

“I don’t know why people expect art to make sense. They accept the fact that life doesn’t make any sense,” said David Lynch. I admire Lynch’s attitude to art, but I don’t think he was quite right about our attitude to life.

We strongly resist the idea that the universe is random and meaningless. Stories are conjured out of chaos, significance is found in tea-leaves. One of the most consistent findings in cognitive science is that people are made anxious by ambiguity and seek to reduce uncertainty. Humans are pareidolic creatures, wired to look for coherent patterns in the data. When no such patterns exist, we impose them. Hence conspiracy theories, spurious correlations, and, perhaps, art itself.

Having said that, I do think Lynch was right to suggest that people don’t necessarily want everything to make rational, explicit, articulated sense. We find profound meaning in things that we don’t understand. Some of the most potent dreams, stories, poems and images remain impervious to explanation; they just are, and we love them for it. In another interview, Lynch said, “Certain things are just so beautiful to me, and I don’t know why. Certain things make so much sense, and it’s hard to explain.”

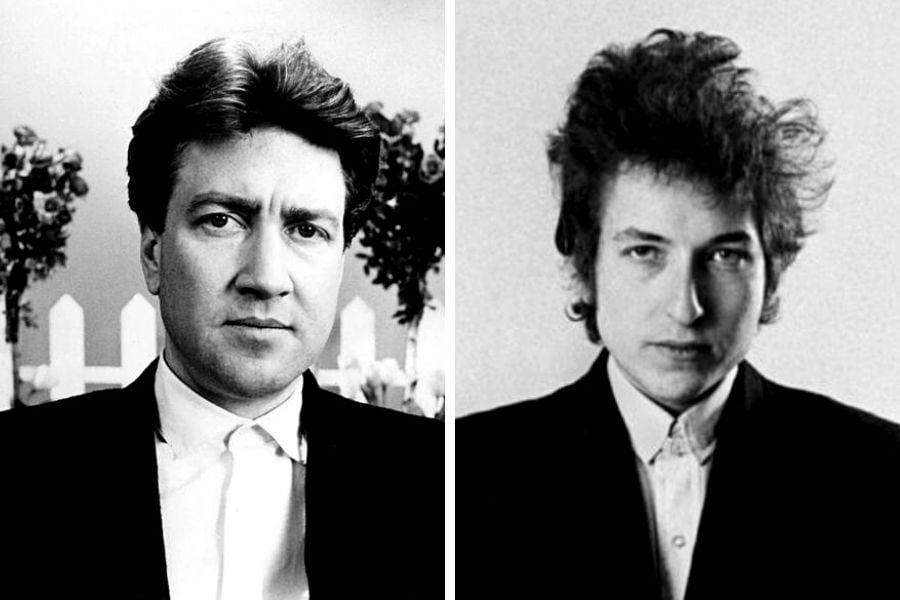

Sometimes we want the kind of meaning you can explain and sometimes we want the kind of meaning you just feel. Art (in the broadest sense) can deliver both, sometimes at once, but different kinds of art lean one way or the other. The market, however, has a bias towards the easily comprehensible, the conventional and the formulaic. Only a few artists achieve mass popularity while making art that is defiantly hard to understand. David Lynch was one. Bob Dylan was another.

These two artists, who both came of age in the post-war period, shared a disdain for the explicable (I’m using the past tense for simplicity, even though Dylan is very much still with us). Each made art that baffles and disorients even as it enchants. Both were immersed in the pre-rational - in myth and symbol and the supernatural. Both have legions of obsessive fans who pore over every film or song like detectives searching for answers. And both always denied having any such answers, swerving requests to explain their work.

In 2025, Lynch and Dylan seem braver and more radical than ever, since we live in a culture increasingly hostile to ambiguity. Artists seeking commercial success are pressured to be instantly legible in form and content. If you want to have a hit song, you’d better ensure listeners know it’s going and what it’s about within the first minute. If you want a hit movie, you’d better make sure the audience quickly understands everyone’s motivations and goals.

A Complete Unknown is a conventional, graspable biopic in most ways, but I liked that it did not try to ‘explain’ Bob Dylan. Instead, it embraced his essential inscrutability; hence the title. It didn’t try to insert some hidden childhood trauma, some Minnesota Rosebud, to account for Dylan’s relentless creative drive. It accepted that we’ll never know why Dylan is Dylan. In a world where every hero and every villain must have a trauma plot, that was refreshing.1

In my book Curious I discussed a distinction, borrowed from intelligence-gathering, between puzzles and mysteries. A puzzle is “How many ballistic missiles does Iran have? A mystery is, “What does Iran want?”. Puzzles and mysteries both pose questions, but only puzzles have definitive answers. When you’re solving a crossword or a maths problem, you know there’s one right answer and that all others are wrong. With mysteries, right and wrong are approximate and fluid.

Where puzzles are orderly and coherent, mysteries are murky and messy. They pose questions that can’t be definitively answered. In fact, the more answers you get, the more questions you have. A puzzle is disposable: once you have had the satisfaction of solving it, it loses interest. Mysteries can be frustrating, but they’re also endlessly stimulating. An Agatha Christie novel is a puzzle. The Great Gatsby is a mystery. Only one of them bears re-reading.

Mysteries have a longer half-life than puzzles. Shakespeare conceived Hamlet after reading a Scandinavian folk tale in which a young prince, Amleth, wants revenge on the man who killed and usurped his father, the former king. Amleth is smart: he knows he will be under suspicion, so he feigns madness until he’s ready to strike. In Shakespeare’s version, the murder is a secret revealed exclusively to Hamlet by his father’s ghost. Hamlet’s feigned madness, and his delay, are therefore entirely unnecessary. That’s right: Shakespeare took a perfectly good plot and deliberately scrambled it. Imagine him pitching it to a studio. “Willie, we love ya, but this story makes no freaking sense.” Yet centuries later, Hamlet still fascinates us, while Amleth is forgotten.

Artists may relish mysteries, but corporate executives prefer puzzles. Mysteries require more trust in intuition - the artist’s and the audience’s - than puzzles do. Hollywood, before it turned moviemaking into one giant data-based puzzle, used to trust its directors. With Chinatown, Roman Polanski was allowed to take a puzzle-based genre - the detective story - and make a mystery out of it: the mystery of evil.

David Lynch did something similar with Twin Peaks. It’s astonishing that ABC trusted him enough to make it, and a little less surprising that it found an audience. For nearly all of human history we’ve been enthralled by invisible spirits, secret signs, and monsters just of sight. We’re built for mysteries. We all dream. A mystery-spinner as talented as Lynch ought to be able to put us into a trance.2

But it’s harder for artists to cast such spells in an environment that keeps everyone awake. The greatest new art form of the twentieth century reproduced the conditions of a dream: moving images in a dark room. The dominant forms of media in the twenty-first century reproduce insomnia: the ruminating, hyper-alert but exhausted condition required to process a stream of disassociated, anxiety-generating messages. The result is a tyranny of exposition. Netflix executives are reputedly putting pressure on screenwriters to have characters “announce what they’re doing” so that viewers looking down at their phones can keep up with what’s going on.

Similarly, if, as Tyler Cowen suggests, younger people aren’t getting into Dylan anymore, that may be because they’re even less inclined than previous generations to enjoy songs with lyrics that aren’t easy to grasp. The controversy over Dylan’s evolution in 1965 wasn’t just about amplification. Pete Seeger’s dismay was just as much about how this singer of message songs had started going on about ceremonies of the horsemen and magic swirling ships.

Though Seeger seems out of time in the film, he is in some ways a more modern figure than Dylan. We expect our pop singers to make sense and to be morally upright. Insofar as songs invite questions, they tend to be puzzles—Easter Eggs. Fans scour lyrics in search of answers, but in this case the clues are deliberately planted by the artist, and the solutions really do exist. (The great exception here is Lana Del Rey).

Artists who lean into mystery are prone to the charge of bullshit - of stringing any old nonsense together and letting the pattern-seeking instincts of audiences do the rest. There’s certainly no shortage of mediocre abstract art and pretentious song lyrics. What sets the Lynches and Dylans apart from their less talented imitators? Many things, but I think it’s partly the way they convey utter commitment to their strange visions.

Watching Mulholland Drive the other evening, I was struck by how, no matter how bewildered I was, I never felt Lynch was simply throwing tropes together and shaking them around. He somehow imparts an uncanny sense of purpose to it all. He might not have been able to articulate it if asked, but it’s what makes the film so riveting. Similarly, when Dylan sings about smoke pouring out of a boxcar door or a trainload of fools in a magnetic field, I know that he feels the meaning of what he’s singing, because I can hear it in the ferocious conviction of his delivery. And that makes me feel it too.

This piece is free to read, so do share it widely if you enjoyed it, and ‘like’ it.

I’ll be speaking about ‘John & Paul’ at Waterstones in Liverpool (coals, Newcastle) on April 8th. Come along!

After the jump: my thoughts on DeepSeek, plus a rattle bag of juicy links including more Lynch and Dylan. If you’re not already a paid subscriber, please consider signing up. Paid subscriptions get you the best of The Ruffian and they are what enable me to write this newsletter. Don’t think twice.