The End of History

Academic historians are destroying their own discipline

Catch-up service:

- Thirty-One Insights Into Art, Writing and the Creative Process

- John and Paul - news about my forthcoming book

- Stories Are Bad For Your Intelligence

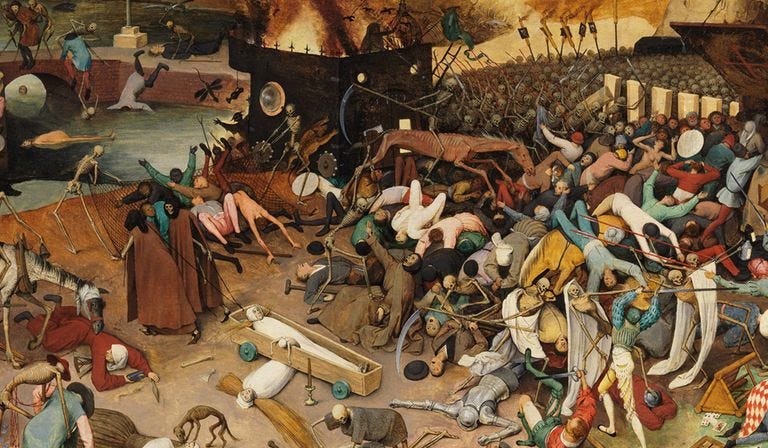

The Black Death, a bubonic plague, devastated Europe between 1346 and 1353. It reached England in 1348 and proceeded to wipe out between a third and a half of the population in about a year. Spread by flea-infested rats, it tore through the densely populated area of London, reducing the city’s population from about 100,000 to about 20,000. (The longer-term upside is that it raised the wages of labourers in years to come, though I guess that might not have been much comfort at the time.)

It’s difficult to uncover new insights into an event that happened so long ago and which has been so well studied. But anthropologists associated with the Museum of London have done just that, according to a report from the BBC this week. It says: “Black women of African descent were more likely to die of the medieval plague in London, academics at the Museum of London have found.”

Wow. How can they tell? Well, the researchers studied “a database of bone and dental changes” of 145 skeletons from three of the cemeteries in which London’s plague victims are buried. Using a “forensic anthropological toolkit” they claim to have determined whether the bones are likely to have come from someone with African heritage, and to have established that there are “significantly higher proportions of people of colour and of Black African descent in plague burials compared to non-plague burials (18.4% vs. 8.3%).” They add:

"For the female-only sample, individuals of estimated African population affinity have a significantly higher estimated hazard of dying of plague compared to those with estimated white European affinity. There are no significant associations for any of the other comparisons."

The researchers conclude that this higher death rate is evidence of the “devastating effects” of “premodern structural racism”. Sharon DeWitte, a biological anthropologist from the University of Colorado, says “it shows that there is a deep history of social marginalization shaping health and vulnerability to disease in human populations."

Hmm.

It’s true that the Black Death hit people from different social categories differently - if you were a noble you could wait it out in your castle in the countryside; if you were a poor urbanite, there was no escaping it. But, c’mon. To state the obvious - and it seems we must - there were vanishingly few black people in London in the mid-fourteenth century.1 England was overwhelmingly white. The researchers gesture towards rich merchants visiting London from overseas, some of whom might have had servants from Africa. But that wouldn’t even begin to explain what they are claiming to have found.

The sample size, by necessity, is tiny. To be clear, of those 145 individuals, only some died from the plague. Of those who did, the researchers find that 18% were black! Nearly a fifth! Given that the black population of London would have been quite a lot less than 1%, that’s some incredible ratio. If you’re a scientist and you get a result like that, you should be asking serious questions about your methodology.

Oh I nearly forgot, they’re drawing these weighty conclusions from an even smaller sample - from the bones they claim to have identified as belonging to black women. The plague killed men at a higher rate than women, by the way. Implausibility piles on implausibility. This is before we even get into whether the category of “black” is remotely meaningful here, or exactly how they think the mechanism of “structural racism” worked, which would require actual historical knowledge.

In short: either there was some utterly wild disparity in the way different races were hit by the bubonic plague in London - or maybe the researchers aren’t identifying what they think they’re identifying. I rather suspect the latter.

One of the researchers is Rebecca Redfern, senior curator of Archaeology at the Museum of London. She’s behind several stories in the media over recent years that claim to find Britain was more diverse that previously thought. In this study she uses the measurement of skulls to identify racial heritage, a method whose scientific credibility is deeply questionable, to put it mildly. It’s funny that while some academics claim to have debunked the notion that race has any firm biological basis at all, for others, nineteenth-century-style racial craniometry is still a going concern.

Look, I haven’t carried out a full investigation of this paper, but I already feel like I’ve spent too long on it. It is just obviously bullshit. Now, you might say, perhaps that’s OK? The Museum of London needs publicity, stories about structural racism are popular at the moment, why shouldn’t they direct attention to an important aspect of our history, while showing that ancient history can be relevant to current concerns? Maybe this is good bullshit!

I think it’s bad bullshit. Here’s Feyi Fawehinmi, a black Briton, and author of an acclaimed book on the formation of Nigeria:

I don’t know if it opens black people to ridicule - it certainly makes the academics look ridiculous - but I agree that this kind of thing is, at root, an act of disrespect to black Britons, who did not ask and do not need (largely white) academics to perpetrate acts of dishonesty and stupidity on their behalf in order to feel at home. They know, we all know, that the academics are not really doing it for them, anyway. They’re doing it for themselves - to get publicity, and above all to show their peers that they know where it’s at. Whole fields of historical study seem to have turned into competitions for who can generate the most eye-catching narrative of identity-based injustice, and if that means making blatantly implausible empirical claims, so be it. To me this seems a very bad thing for the authority of History as a discipline.

A couple of months back I wrote about an example of this tendency, in a post entitled Stories Are Bad For Your Intelligence. Just last week, we got an update on this affair. It’s quite something.

If you haven’t read my post, give it a go. It’s about a paper by a UCL historian called Jenny Bulstrode which claims that the English industrialist Henry Cort stole his innovative method of iron production from a group of black slaves who worked in an iron foundry in Jamaica - despite the fact that Cort never visited Jamaica, or had any established contact with anyone who had anything to do with anyone in the foundry, and despite there being no evidence that these slaves did invent a new process, or that the foundry ever used anything resembling Cort’s process. Honestly, if you think I’m exaggerating, read my piece and follow the links, and/or read Anton Howes’ first piece on the paper’s gaping holes.

After Anton and a few others brought attention to these problems, I anticipated that the journal would have to withdraw the Bulstrode paper, or least issue an apology for it. Anton warned that a withdrawal was never very likely since the field of history doesn’t operate on a very scientific basis. Still, they would surely make some concessions - perhaps admit that the paper, uh, stated its conclusions with too much certainty, or something like that?

Nope.

The journal, History and Technology, has just declared “unreserved support” for the article. Its editors, a pair of American academics, have written their own review of Bulstrode’s paper and the criticisms of it, and they insist that the original paper “upholds all scholarly standards”. The editors/reviewers, Amy Slaton and Tiago Saraiva, both of Drexel University, have put themselves in an odd position of being both jury and counsel for the defence, and they do not give an inch on behalf of their client. Actually, that’s not quite true; they concede, rather grudgingly, to one error in Bulstrode’s paper. Other than that, they go all in.

When I saw that they were mounting a defence I looked forward to reading a detailed refutation of the points made by Howes and by Oliver Jelf. Honestly, nothing would have delighted me more than to have to come back here and say ‘There’s another way of looking at this altogether.’ Reader, I was disappointed. I was amazed, actually.

First of all, there is the paper’s tone: peevish, pompous and rude. The reviewers cite Howes and Jelf in the footnotes but don’t stoop to mention them in the text, or give them any credit for their careful work on exposing the paper’s flaws. Secondly, and most amazingly, there is barely a factually-based argument in the whole article. It is a vacuous, entirely superficial piece, written in the jargon-ridden, bloated prose of critical theory as filtered through history departments.2

It’s divided into two parts. Part I is called “Facts and findings” which I will warn you right now is misleading advertising. They spend much of this section restating Bulstrode’s case while doing some irascible handwaving:

Bulstrode’s article is not about the unsung Black heroes of the Industrial Revolution but an exploration of Black metallurgists’ technological practices in their own terms. Such terms include African cosmologies associated with iron making reworked in Jamaica through experiences of enslavement in sugar plantations and marronage. Detractors of Bulstrode’s article repeatedly ignore this central point of Bulstrode’s text, leading in large measure we believe to their inadequately substantiated claims of a lack of evidence and their contestation of Bulstrode’s reading of sources.

This is really besides the point. Whatever the article is ‘about’, it makes bold empirical claims to do with Henry Cort’s theft of intellectual property. These claims are why it attracted so much publicity. Its critics have pointed out the claims are not evidenced.3 That’s why we’re discussing this. Towards the end of this paragraph the reviewers finally get to the “claims of a lack of evidence”. Oh good, here come the facts and findings!

Well, no. They largely summarise Bulstrode’s case and declare it good, without addressing the critiques directly or citing any new evidence. They repeat the same fatal confusion the article makes, between the iron rollers used on Jamaican sugar plantations, and rollers through which Cort fed scrap metal in his factory (by the way, the rollers were only part of the process that Cort patented, something Bulstrode et al ignore altogether). As Anton Howes has already explained, these are two different species of roller. Elsewhere the reviewers loftily dismiss such distinctions as “arbitrary demarcations among forms and functions.” Well, good to get that cleared up.

Anyway, the roller question is quite a way down the list of errors, unsupported assumptions and wild implausibilities in Bulstrode’s phantasmal paper, and the reviewers do not confront any of them. They say:

It is thus sound to conclude, as Bulstrode does, that people who were so familiar with both sugar and iron production overlapped in their approaches to the two operations and passed bundles of scrap metal through grooved rollers.

I mean, no it’s not, but also, what on earth do they mean by “their approaches to the two operations”? The people we’re talking about were slaves in an ironworks. Presumably they did not get to have “approaches to the operations”. Presumably they had to do what they were told. I very much doubt they were invited by their masters to dream up a better, more innovative production process (“We really value your input, guys”). They weren’t sitting around on beanbags, brainstorming new ideas for iron manufacture. They certainly had no incentive to make the company for which they worked more profitable. This is before we get to the point that there’s zero evidence that the factory in which they worked housed any innovations, or made any more profit than you would expect for an ironworks in its situation.

The reviewers wrap up their section on rollers with this:

She importantly asserts that the specific technological practice described by Cort’s patent is the result of transitions between sugar and iron technologies performed through concrete labor and ritual practices of Black people in Jamaica.

Well, yes, exactly, she asserts it, importantly or otherwise. Unfortunately, she doesn’t come anywhere close to proving it or to showing it’s even plausible, let alone likely. It’s the job of a reviewer to notice that.

They now move on to the next major part of the Bulstrode story - how Cort came to learn of this Jamaican factory’s (non-existent, as far as we know) innovation, despite never having visited it and having no documented connection to it whatsoever. Bulstrode’s case is that a man called John Cort (possibly a distant relative of Henry, but, shrug) travelled from Jamaica to Portsmouth - and so perhaps he tipped off Henry when he got there. She found the ship he travelled on. As it turns out - and this is the one factual error the reviewers deign to acknowledge - John Cort landed at Lancaster, about 300 miles away. But no matter! It’s definitely true that some ships travelled between Jamaica and Portsmouth!

This said, the argument remains in place. The important fact to retain is the connection established between Portsmouth and Jamaica through ships that needed to be repaired on both sides of the Atlantic with iron pieces.

Well, there you go. Forget about John Cort. The point is that Henry Cort can hardly failed to have found out about this exciting new ironworking process (which we have no evidence existed) invented by black slaves (who almost certainly had no opportunity or incentive to innovate)…somehow. Cough. Let’s move on.

Part II is a meta-discussion of how history should be conducted. Here you sense the reviewers stretching their legs and really enjoying themselves, as they finally enter the comfort zone of theory, where they no longer have to even pretend to be interested in the bothersome and trivial business of historical fact. I won’t torture you or me by attempting a summary of this part, but you get a flavour of it from the concluding paragraph, in which they rather give the game away:

We by no means hold that ‘fiction’ is a meaningless category – dishonesty and fabrication in academic scholarship are ethically unacceptable. But we do believe that what counts as accountability to our historical subjects, our readers and our own communities is not singular or to be dictated prior to engaging in historical study. If we are to confront the anti-Blackness of EuroAmerican intellectual traditions…we must grasp that what is experienced by dominant actors in EuroAmerican cultures as ‘empiricism’ is deeply conditioned by the predicating logics of colonialism and racial capitalism. To do otherwise is to reinstate older forms of profoundly selective historicism that support white domination.4

If you say, in effect, “we don’t think historical research should be fictional, but…” you are implying that a little fiction is OK. Not just OK, actually, but a righteous strike against Western empiricism and thus “white domination”. The reviewers pretty much openly declare that the meta-narrative which they and Bulstrode wish to push is more important than faithfulness to historical reality. When I wrote Stories Are Bad For Your Intelligence I’m afraid I may have under-estimated quite how widespread and stubbornly held this mindset is among academic historians.

As soon as this deeply inadequate review was published, historians leapt to Twitter to endorse it, and to support Bulstrode. Professor Jack Stilgoe of UCL, a colleague of Bulstode, declared that her paper had been “bolstered” by the article and that it is “a brilliant piece of historical research”. Professor Alan Lester, of Sussex University, wrote an exceedingly long tweet asserting similar. Professor David Andress of the University of Portsmouth, saw fit to accuse Bulstrode’s critics of racism. In case you think I’m cherry-picking a few academics on Twitter, here’s an official, registered, learned society:

I am naive enough to be flabbergasted by all this. I almost want to say to them, Have you actually read the Bulstrode article? And have you actually understood the criticisms of it? Have you actually read this embarrassingly shoddy review? Because it’s genuinely hard to see how you could any of this and still hold these opinions. And if you genuinely do, what are we to make of your research?

The insinuation of racism is particularly stupid and infuriating. It’s not racist to want strong historical claims to be rooted in evidence. What I do think veers close to racism is using the historical memory of Jamaican slaves instrumentally - as tokens in an academic status game. For all that Bulstrode and her allies claim giving black people a voice, they don’t successfully portray the slaves as real historical actors at all, but as imaginary paragons (skilled ‘metallurgists’, conceptual innovators, custodians of ancient traditions, noble freedom fighters). The actual analysis of African/Jamaican lives seems to be millimetre-deep. As I said in my piece, there is a quasi-Orientalist strain to this. Neither Bulstrode nor the reviewers saw fit to cite historians of Western Africa. The “metallurgists” exist to burnish Western academic reputations.

What this review, and the reaction to it, shows us, is that the problem here extends far beyond one paper, and one author. This is an institutional malaise.

In recent years there has been a precipitous, worldwide decline in the number of young people choosing to study the humanities, including history. Governments are funnelling resources towards STEM, and universities are responding to signals from the marketplace. But the humanities are also under assault from within; from a cohort of academics who have been raised in the deadening, homogenising discourse of critical theory (or a rather, a degraded version of it) and who are now abandoning the principles which made their discipline authoritative and vital in the first place.

There really isn’t much point in studying literature if you don’t value it as an end in itself rather than just a method of social activism and there is certainly no point in studying history if you don’t believe in the primacy of empirical evidence. If you want to tell the story of the Industrial Revolution as one of exploitation of black technological practices, that’s fine, but it has to be securely rooted in evidence. If it’s just a story, it’s worse than worthless.

If History is to be dominated by Bulstrodes, Slatons and Saraivas, all telling each other they’re doing fine and noble work in the name of social justice, then it will inevitably disappear from the mainstream of higher education - and what’s more, we shan’t miss it. To save the discipline from irrelevance, historians of integrity need to stand up and start calling this bullshit out, loudly, rather than muttering behind their hands while quietly going along with it.

I don’t know who this person is but her tweet (in response to Alan Lester’s endorsement of the review) says it all:

I haven’t been able to find hard data/evidence on non-white people in London in the fourteenth century. I think the consensus is there were only a handful. David Olsuga’s history of black Britons doesn’t mention any.

A note on ‘jargon’. There is nothing wrong with jargon per se. Every specialist domain has its technical terminology. Jargon has the drawback of excluding outsiders, but the benefit of speeding up communication among insiders. I’m sympathetic to specialists who say, in response to critics, well, we know what we mean, and if you want to understand it too, do the work. But there is another drawback to jargon: it can be used to obscure an absence of actual thinking and actual knowledge. One academic who acclaimed the Bulstrode paper when it came out tweeted about the ‘semiotics of ironwork’ even though the paper has nothing to do with semiotics. Sometimes the use of jargon isn’t a way for very smart people to speak to each other in high-level code, but a method by which mediocrities can signal to one another that they belong to the same tribe, without having to do any actual work.

Note that the reviewers uncritically adopt Bulstrode’s habit of calling the Jamaican ironworkers “metallurgists”. She uses it on the basis that some of them, and/or their African progenitors, probably had ironworking skills. Bulstrode and the reviewers are very keen on this scientific (‘sciencey’) label, which is rather odd for academics so keen to respect non-Western forms of knowledge. As for “African cosmologies” - I don’t know, and I suspect they don’t either.

Aren’t they just saying that black voices have been excluded from Western histories? No, I don’t think so. I think they’re questioning the principle of empiricism itself. The writing, as is often the case with this kind of material, is foggy enough to allow different interpretations, but to me the implication is clear enough, and explains the shockingly cavalier approach to evidence they exhibit in the first part of the article.

Older professional historians have been aware of the decline of their field since at least the 1990s. The decline of narrative history and the rise of micro history, post modern history, history as cultural criticism, etc has led to an identity crisis of sorts for what it means to be an historian. Gordon Wood, now retired from Brown wrote in 2008 “Present-day graduate students of history are well aware that ‘race, class and gender’ is the mantra they must repeat as they proceed through their studies...yet so suffocating has been the stress on ‘race, class, gender’ issues that sometimes beginning graduate students hesitate to write about anything else.” Tony Judt (1945-2010) was even more scathing in his views on his peers refusal to call out nonsense when they saw it. The fear of being considered old fashioned or unwilling to accept new ideas is pervasive, even when those ideas (see post modern structuralist thought) are destructive to the very work they are engaged in. Wood’s collected book reviews are a helpful antidote. The Purpose of the Past: Reflections on the Uses of History. Also Judt’s When the Facts Change: Essays 1995-2010.

While lamenting this regrettable trend, we should not lose sight of the fact this stuff is exceedingly funny. Measuring skulls to prove racism – poetry.