What 'Adolescence' Doesn't Tell Us About Boys

Impressive Entertainment, Not Sure About the Social Commentary

Catch-up service:

Did Lennon Think He Was Jesus?

Why It’s Hard To Stop AIs Lying

The Hipster-Military-Industrial Complex

The Ruffian Speaks

The Audacity of Ambition

This week John & Paul was officially published in the UK! That means that if you live here you can no longer pre-order - boo - but you can simply order: retailer links here. And guess what American readers? You still have a couple of weeks left to pre-order!

Touched and delighted by this beautiful response to the book from none other than Nigella Lawson, both because she’s such a fine writer and reader and because I really want this book to be read by people who aren’t Beatles fans or even music fans. John & Paul tells a story that I think anyone can be moved by.

I have a feature in the Guardian today comparing Lennon and McCartney to other intense male friendships/collaborations.

On the morning of publication day I appeared BBC Radio’s Today programme to talk J&P. UK readers can listen here, I’m in the final slot, at 8.55am.

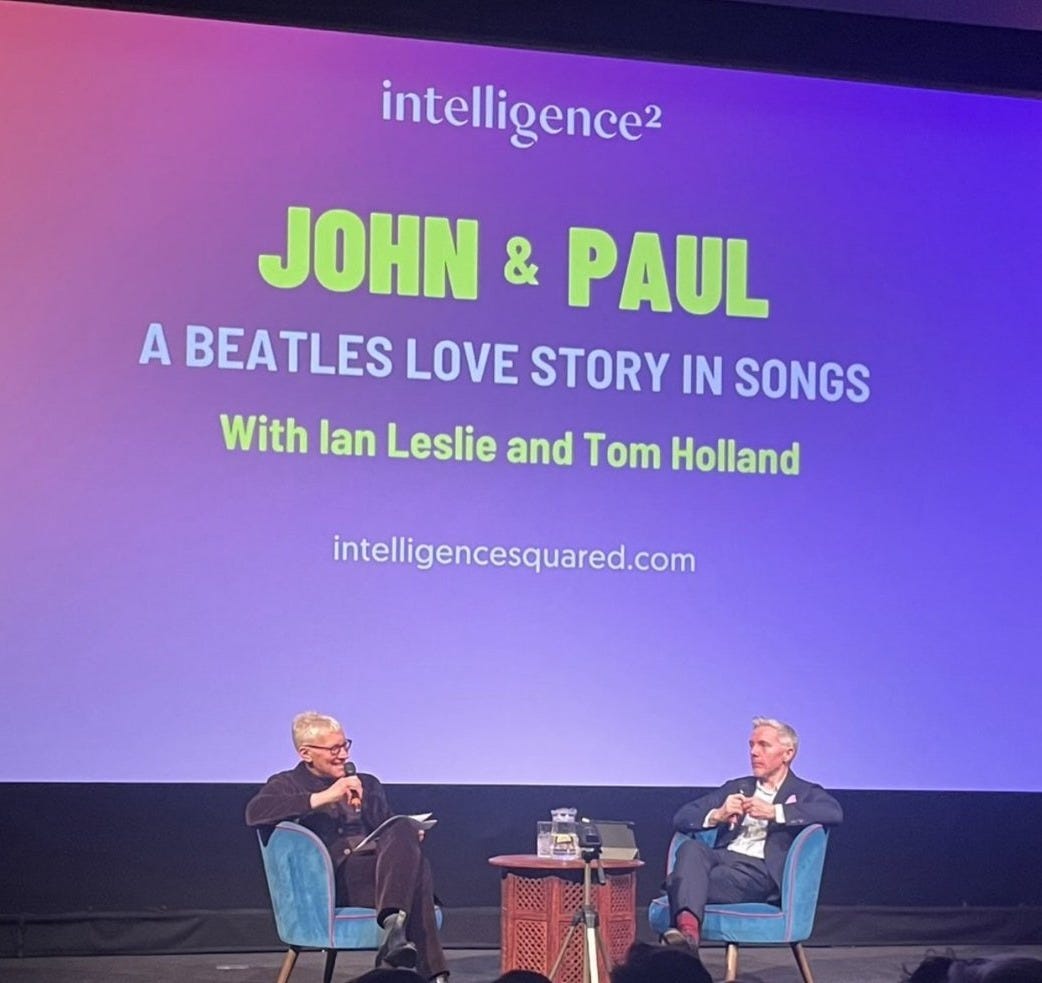

In the evening I had the privilege of playing Dominic Sandbrook to Tom Holland’s, er, Tom Holland. Tom interviewed me on stage at the Kiln Theatre in Kilburn, West London. It was a hugely exciting night (for me anyway). Thanks to Tom and everyone who came along. It was great to meet some Ruffian readers at the book signing afterwards.

What 'Adolescence' Doesn't Tell Us About Boys

Adolescence is a phenomenon. As of writing, it is Netflix’s top rated show globally. That is quite an achievement for a bleak English drama set in distinctly unglamorous locations, without famous stars, sex scenes, or dragons. Adolescence has succeeded so wildly in part because it’s very well made. It’s also because the show is a heat-seeking missile, with controls set for the heart of the discourse.

Everyone wants to talk about Adolescence. Or rather, everyone wants to talk about what the show invites us to talk about: the problem with boys. We, the grown-ups, have long been worried about the apparently rising popularity of misogynist influencers and attitudes, which seems to be accompanied by anomie and anxiety among teenagers and young men. The creators of Adolescence have taken those concerns and, with considerable skill, distilled them into a fissile isotope packed with explosive cultural energy.

At the centre of the story is a boy who stabs a girl to death in a fit of rage, driven by fear of masculine humiliation. Jamie is intelligent, and while he has problems controlling his anger, he is not mentally ill. Jamie’s normality is crucial to what you might call the argument of Adolescence. We have seen dramas about children doing terrible things before and invariably it turns out that the children’s parents have done terrible things to them.

Adolescence toys with with this convention, leading us to expect a shocking revelation of parental abuse. The only shock turns out to be that Jamie’s parents are decent and loving. They are not the problem; the problem is in the phones. Jamie’s mind has been poisoned by the online ‘manosphere’ (a concept clumsily introduced in a scene between the lead detective and his son). This online culture is to blame, rather than parents, teachers, or the kid himself. The manosphere performs a role that we used to assign to evil spirits, arbitrarily taking possession of vulnerable souls and acting through them to commit awful deeds.

Jack Thorne, the writer of Adolescence, puts it like this: “[Jamie] comes from a good background, like me; he’s a bright boy, like I was. The key difference between us? He had the internet to read at night whereas I had Terry Pratchett and Judy Blume.” Your beloved son could be the next Jamie, the story tells us. This is a terrifying and riveting thought. It is also, let’s be clear, quite mad. I don’t believe for a moment that if Jack Thorne had had access to Andrew Tate videos he would have turned into a rage-fuelled murderer, and in general there is no empirical support for such a proposition.

If there had been a spate of murders of girls carried out by mentally stable, otherwise law-abiding boys, the show’s premise would be more realistic. But there has not been. In interviews, the show’s co-creator, Stephen Graham, has cited, in an offhand way, a few murder cases, but as far as I can see none of them have been connected with the manosphere, and the perpetrators have preceding problems - mental illness, criminal records, gang involvement. Jamie is not a real life character in any sense. Thorne himself says: “There is no part of this that's based on a true story, not one single part”. I believe him. In order to target the manosphere, the creators of Adolescence felt they had to exclude all usual causes. But they did so at the cost of social and psychological truth.

Thorne’s account of how he came up with the character of Jamie is almost comically straightforward. Graham had suggested making a show about a teenage murderer. Someone Thorne was working with then suggested he look into ‘incel culture’, which was apparently new to him. So he went online and was amazed by what he read, and that was enough to get him going. According to this account, he didn’t personally know anyone who had been drawn into this dark world. He didn’t spend months or years immersed in the world of teenage males, trawling forums, reading court transcripts, seeking out face-to-face conversations with offenders, affected families, psychologists. He did a Google search and opened Final Draft.1

As we know, the internet can be an outrage generator, a hot take machine which tells you what you already want to believe. In reality, incels are a negligibly tiny group of men who post repellent content online, their actual significance wildly overstated because they make for such a good, clickable story. As the FT’s data-based columnist John Burn-Murdoch puts it, “I find almost every mention of ‘incel’ in mainstream discourse to be a red flag signalling that what follows can be ignored as fact-free.”

More broadly, it’s surprisingly hard to find strong evidence that there is a rising tide of misogyny, or misogynistic violence carried out by young men, or to peg real world crimes and misdemeanours to online culture. Countless apparently evidence-based headlines have been generated by statistics that don’t show trend-lines, trend-lines that don’t reflect changes in reporting, spurious causality claims, reliance on small or unrepresentative samples, and failures to account for confounding variables. Some evidence points in a different direction altogether.

I don’t think it is all a fuss about nothing. If we don’t have good evidence for rising misogyny that might be because we have never really measured it properly. And there are just too many anecdotes - teachers reporting a rise in misogynist language from pupils, the immense popularity of certain influencers - to say there is nothing wrong here. (People love to say that the plural of anecdote isn’t data when it actually is.)

It’s just that once you look at what lies behind the headlines and takes you find a lot of different things being smushed together. A rise in the number of young men agreeing that “a woman’s place is in the home” is certainly worth noting but it’s a long way from there to concluding that young men have learnt to despise women, let alone that many of them are now a hair trigger away from stabbing a girl to death. We should try and be clear about which problems are which, rather than mixing them all together and shouting manosphere or toxic masculinity.

I’m not sure the creators of Adolescence got beyond this blob of takes. If screenwriters are looking to investigate cultural or structural causes of misogyny and male violence in Britain, then “honour-based” killing and abuse is surely a more substantial and urgent problem than the manosphere. I would sincerely love to see a TV drama about that, preferably written by someone from the relevant communities, though I’m not expecting to see one any time soon.

Thorne’s shallow engagement with the complex topic of young male dysfunction mirrors the behaviour that his show imagines teenage boys to be engaged in: sucking up the internet’s most dazzling and lurid content without applying scepticism or critical thinking to it. The same goes for critics and commentators who have gushed over his show. There’s much to admire about Adolescence, including the incredible performance of Owen Cooper, and the show’s daring formal innovations.

But ultimately it is clickbait as much as it is realistic human drama or reportage. It uses the murder of a young girl as its fissile material without being interested in either the murder or the girl. The stabbing is neither shown nor described in detail and remains distant, unreal, disembodied. We learn nothing about Katie, except that she could be a bit of a bitch. Thorne has described TV as an empathy box, but in this show, only the boys are allowed inside.

Fear about what popular culture is doing to our children is a perennial theme. In terms of mainstream impact, hip-hop came into its own in the 1990s and early 2000s. It was frequently misogynist, brutal and violent. Several of its biggest stars were, in persona at least, gun-toting, nihilistic gangsters. Its rise was accompanied by a fear that it was poisoning the minds of a generation of young men.

It would be glib to retrospectively dismiss all those concerns as “moral panic”, but hip-hop’s critics over-estimated the extent to which its fans took its gangster ethos seriously, rather than assimilating it into a knowing and ironic repertoire of self-expression. I think it’s fair to say that nobody looks back on the mainstreaming of hip-hop as a significant turning point in male attitudes to women, or as a major cause of violence (indeed violent crime went steeply down during the 1990s). I wonder if it’s any more likely that in twenty years we’ll look back on the emergence of the manosphere as a pivotal social change.

Adolescence is an entertainment, not a documentary. Keir Starmer has recommended that it be shown in schools, and while I don’t think the show tells us much about British society, I have no objection to that. It can’t do kids any harm to watch such a cleverly made work of fiction.

If you enjoyed this piece, please share and ‘like’. After the jump, for paid subscribers only, more thoughts on Adolescence (from a creative perspective) plus what I’ve been reading and listening to. If you haven’t signed up for a paid subscription yet please do, paid subs are what make my writing possible.