Why You Have an Obligation To Be Optimistic

The Ethics of Emotional Disposition

Catch-up service:

Britain’s Peculiar Brand of Patriotism In Three Ads

Why Things Might Actually Be About To Get Better

Seven Underrated Forms of Diversity

Why Margaret Thatcher Didn’t Jump

There’s no question about it: in elite circles, pessimism is cooler than optimism. If you want to cultivate a reputation for intelligence and sagacity, your best bet is to assert that things are terrible and about to get worse. To be optimistic is to expose yourself to the charge of naivety, and there few things more damaging to the aspirant public intellectual than that. This imbalance applies across the political spectrum, although on the left it is compounded by a sense that to be optimistic is to be uncaring and irresponsible.

A respectable version of the latter case is made by a school of psychologists who argue that people trick themselves into optimism about the social order because they don’t want to confront its injustices. Those disadvantaged by it are motivated to accept their lot and believe it will improve; those advantaged have an interest in defending the status quo; everyone conspires to deny or minimise social problems. This idea, known as “system justification”, is a little hard to square with data showing that most Americans, left and right, are pessimistic about the country’s future. Indeed, the cognitive distortion seems to go the other way.

In 2023, a team led by the political scientist Philip Tetlock set out to test system justification theory. First, they identified some metrics on which American society has objectively improved over the previous twenty years: falling teen pregnancies; a decline in the poverty rate, especially among African-Americans; fewer kids dropping out of school. Then they asked a cross-section of the American population whether they perceived those things to be getting better or worse. They found a surprising degree of unanimity: “Americans are united in their belief that things are getting worse than they really are.”

Negative illusions are harmful. It’s no coincidence that as Americans have become more pessimistic, they have become less happy, or that the people who have the most amount of future ahead of them - the young - are unhappiest of all. Neither is it surprising that people on the left are unhappier than people on the right.

Imagine you have a stock of pills which make you feel a little happier, and a little less likely to succumb to ennui and depression. These wonder pills have no unhealthy side-effects - indeed, their only side-effect is to make you physically as well as mentally healthier. Assuming you have abundant stock, wouldn’t you want to offer them to your friends, and indeed to everyone you encounter?

I believe this is how we should think about optimism, and the projection of optimism. For two reasons.

First of all, if optimism were a pill, we would take it. Optimism is related to fewer symptoms of depression and higher levels of wellbeing. Optimists are better at coping with adverse events, and deal with negative information more calmly. When people are more hopeful about the future, they take more care of themselves: optimism is associated with better cardiovascular health and more resilience to disease. Optimistic people are more likely to take action to solve problems; to create new ideas and new businesses.

Like most pills, this one can be dangerous in very large quantities. Gamblers who are too optimistic will lose all their money; politicians who believe they can’t lose will come crashing down. But in sensible amounts, optimism is very good for us.

Second, this is a pill we can give to others - and by doing so, make it more likely they pass it on. Optimism is contagious. This is because it is less of an intellectual position than a disposition: an attitude or mood. It’s been proven time and again that emotional states spread from person to person. We’re all subconsciously, but significantly, influenced by those who surround us. This is especially true of young people, who are their most porous and malleable.

The latest evidence for mental and emotional contagion comes from Finland, in a paper published in JAMA Psychiatry. The researchers analysed a database of information on more than 700,000 Finnish individuals born between 1985 and 1997. They tracked the progress of each cohort from ninth grade at school (approximately 16 years old) through to adult life.

What they found is that ninth-graders who had one or more classmates with a mental illness were then significantly more likely to develop a mental illness themselves in subsequent years. The effect was particularly strong for depression and anxiety. There was a dose-response relationship: people with two or more classmates with a mental illness were at a greater risk than those with only one. (Causation is always fuzzy in these studies but the researchers controlled for a range of other factors associated with mental illness).

I’m not suggesting pessimism is a mental disorder, or that by being pessimistic you’re going to make anyone ill, but the point is that mental and emotional states are not self-contained. They involve what economists call externalities, or spillover effects: unintended consequences for those in our vicinity, real or virtual. Moods spread fast through social media, and young people in particular are so plugged into social networks that they live inside a more volatile emotional weather system than any previous generation.

We’re used to the idea that when it comes to what we buy or how we heat our homes, we have wider social responsibilities. We’re less used to thinking this way about the choices we make in how we project moods or emotions. But perhaps we should.

This is not an argument for dishonesty, by the way: if you’re feeling miserable, you should be under no compunction to put on a brave face. It’s merely a suggestion that we be aware of the external costs and benefits of our behaviour, and factor them in to how we present ourselves in public. If you post a thread in which you express hopelessness about the state of the world, you’ll likely be making others feel a little more anxious and hopeless. Is your message really so important that you think that’s worth the cost?

Conversely, by expressing optimism, you can make others feel a little better about the world and about their own lives. That’s a public good. Of course, you should only do so if your optimism is realistic and grounded, rather than delusional and mindless. But there’s plenty of scope for that, even when it comes to climate change, the topic on which pessimism is most often, and most flamboyantly, expressed.

A new ethic of responsible optimism is emerging from the some of the smartest thinkers on that topic. Max Roser of Our World In Data and his colleague Hannah Ritchie (check out her book) are both passionate environmentalists. They point out that what we need on climate change is action and innovation, and people are more likely to act and innovate if they believe a positive outcome is possible. Pessimism, by contrast, induces ennui. It tends to paralyse rather than galvanise constructive action.

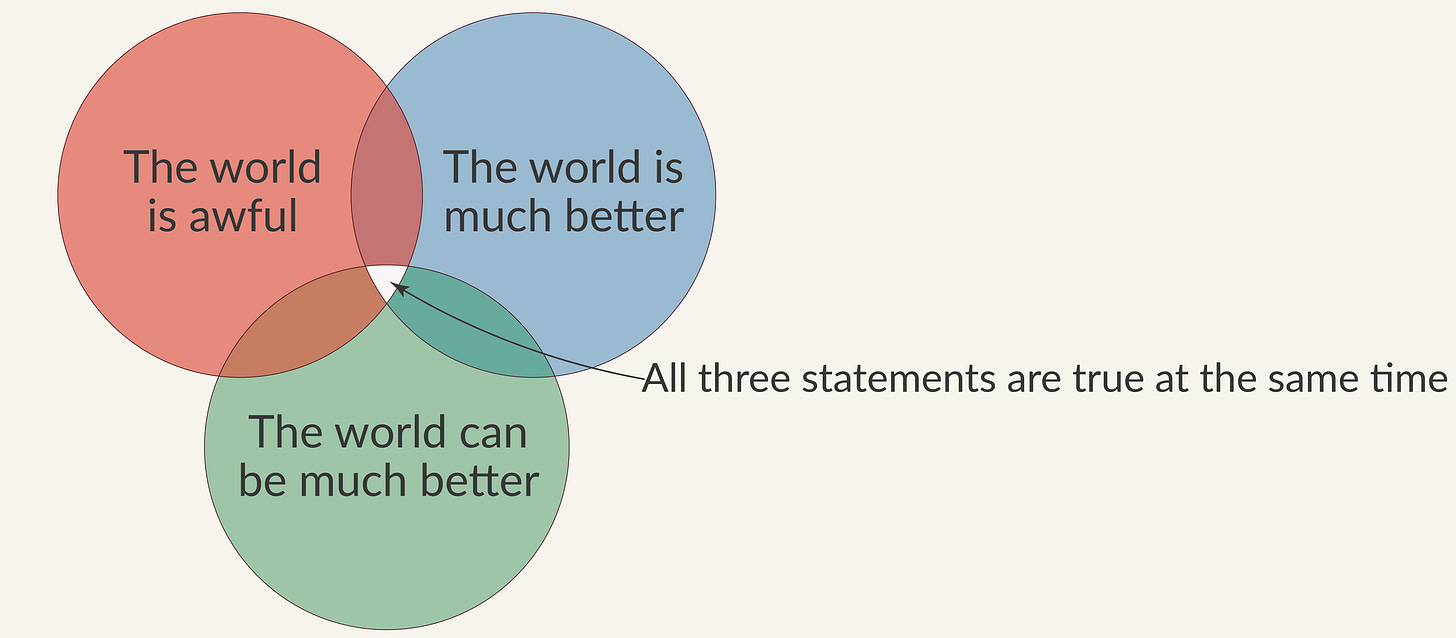

Roser and Ritchie also show, using data and rational argument, that there is plenty to be optimistic about, whether it’s green energy innovation or reductions in poverty. They reject the left-wing idea that to be optimistic is to be blind to tragedy and injustice, and argue instead that one can acknowledge “the world is awful”, while recognising that we’ve made extraordinary progress on human welfare over the last one hundred years, and can do so again in the century to come.

Older thinkers knew that pessimism and optimism are intertwined. Antonio Gramsci talked about “pessimism of the intellect; optimism of the will”. In other words, one should be clear-eyed about the world’s problems, and determined to change them. G.K. Chesterton said, “You need to hate the world enough to change it, but love it enough to consider it worth changing.” Both ingredients are necessary, but the latter must predominate.

As Tetlock shows, the problem we face today is not unrealistic optimism, but unrealistic pessimism. The truth is that, in our validation-needy world, it’s much easier to get attention for alarm calls than rallying cries. Perhaps, then, the forces of pessimism are too powerful to combat. But if I believed that, I wouldn’t have written this.

After the jump:

- Thoughts on the UK election campaign

- A rattle bag of juicy links

- Thanks to you those of you who have taken out paid subscriptions, which are what enable me to do this in the first place. If you haven’t done so yet, please consider it!