Nine Principles For Success In The Age of AI

An Idiosyncratic Career Guide

Catch-up service:

On ‘Adolescence’

Did Lennon Think He Was Jesus?

Why It’s Hard To Stop AIs Lying

The Hipster-Military-Industrial Complex

The Ruffian Speaks

American readers: you have just three more days left to pre-order John & Paul! All orders are appreciated, but pre-orders win you a place in heaven. To encourage you, I have more good notices to share - including the book’s first major American reviews.

The Economist (£) calls J&P “a rich, sensitive reading of the relationship between John Lennon and Sir Paul McCartney”. (Proper titles only at The Economist!).

In a lovely piece in Prospect, Tom Clark says J&P “brims with insights”.

Now, to America. In the Los Angeles Times, Marc Weingarten writes,"We think we know everything [about The Beatles], but author Ian Leslie proves otherwise. His new book, 'John & Paul: A Love Story in Songs,' is, astonishingly, one of the few to offer a detailed narrative of John Lennon and Paul McCartney’s partnership. And it’s a revelation."

All wonderful. But, my friends, I have saved the best to last. Drum roll. Getting a review in the New York Times is a win for any author; getting a really positive review in the NYT is a huge win. So I’d have been delighted with that. But I have a really positive review in the NYT from T-Bone Burnett. That’s insane. If you haven’t heard of him, that’s OK, he’s not exactly famous, but he is one of the most loved and admired musicians in America, a sought-after producer and composer who’s worked with multiple artists, particular on the country/roots/Americana side. He was a guitarist with Bob Dylan in the 1970s, he oversaw the O Brother Where Art Thou soundtrack, he’s produced Elvis Costello albums, he produced Ringo Starr’s new album (which is actually really good!), the list goes on and on. He’s also a huge Beatles fan (if you go to 3m at this video you can hear him explain why they were so different) - and apparently a lovely writer! Who knew?Well, someone at the NYT did. Here’s what T-Bone says about J&P:

Having lived through that period of time myself, it is stunning to follow Leslie’s insights into how far and fast John and Paul traveled, how profound their preternatural alliance was, and how epic their heroic journey. I’m sorry John isn’t here to read this book. I hope if Paul does read it he feels the depth of appreciation and gratitude and intelligence it contains.

I couldn’t be happier.

In other J&P news:My marvellous conversation with Tom Holland (The Rest Is History) on stage at the Kiln Theatre, is now available as a podcast in two parts, via Intelligence Squared.

I was on The Two Matts podcast, one of my favourite conversations about the book so far.

In The Times (£) I gave unsolicited advice to Sam Mendes about his forthcoming Beatles biopic.

I have a short piece in this weekend’s Financial Times, also provoked by the Mendes film, on why The Beatles continue to fascinate us.

In Britain we’ll find out tomorrow if we cracked the Sunday Times bestseller list or not, fingers crossed.

Nine Principles For Success In The Age of AI

I haven’t read many good guides to succeeding or at least surviving in an economy that runs on AI. Having no expertise in either AI or economics, I was a little wary of sharing my own thoughts, but when I consulted with a friend, an expert in both, he pointed out that at this point nobody really knows anything about what’s to come - so why not? This is intended to stimulate, rather than to be definitive or comprehensive.

Let’s assume that we will soon live in a world in which intelligence - narrowly defined - is cheap. In this world, any job that primarily depends on the manipulation of information - on a knowledge of rules, on conventional uses of language, on data-based analysis - comes under threat. Which qualities and attributes become relatively more valuable? Where are the spaces that humans can lean into, at least in the medium term? Here are my guesses, in no particular order (from which I derive my principles, below):

Judgement (wisdom, taste, understanding other humans)

Agency (a sense of purpose or direction, decisiveness, drive)

Physicality (things we can pick up and touch; human presence; human perception; laughter)

Love (empathy, care, affection, relationships in general)

Self-expression (art, meaningful creativity, lateral leaps that aren’t in the training set, ‘voice’ - the inimitable you)

Specialised knowledge (not just information storage, but deep, intuitive, implicit knowledge of a domain)

We have a lot to learn about the future from people who already excel in one or a few of these areas. Artists, performers, athletes, entrepreneurs can be role models even for those of us who do office jobs. Anyway, enough throat-clearing. Here are my nine principles. (First three are free to read).

Don’t be human slop. As has often been remarked, AI is making it much easier to produce “slop” - competently made, eminently passable but fundamentally mediocre content, in writing, TV, music and elsewhere. Given the economics of our creative industries we can expect slop to dominate our screens and speakers for years to come.

Many of us are or have allowed ourselves to become human slop - perfectly good at our jobs but in no way exceptional. In many or most industries, that is going to become harder and harder to sustain as AI gets better at imitating the slop version of different jobs. This might mean sheer volume of output but it probably also means doing the job better and differently to anyone around you.

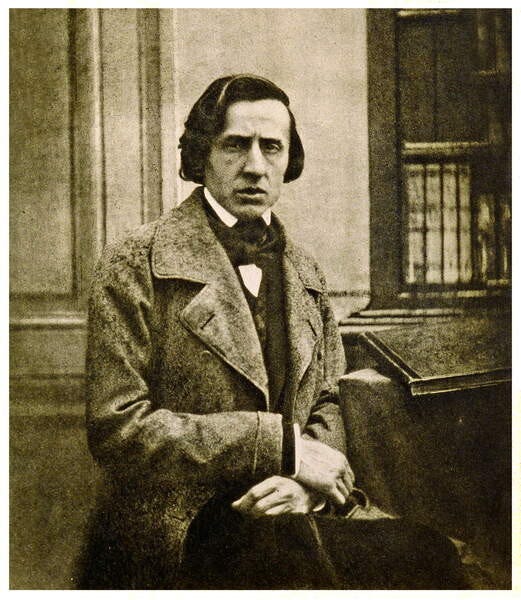

There’s a phrase I often use when I come across work that would have been totally fine if it had been done in the conventional way, but where it’s clear that someone has made an unusual effort to raise to a higher standard: “Better than it needs to be”. (I don’t claim this as original btw!). This should apply to your work, and to you, yourself, in the round: you need to be better than you need to be. This is at least as much about imagination and agency as it is about extra effort.Impose your personality on your work. Here is a story about the great Polish composer, Frédéric Chopin1. In the 1830s, Paris, where Chopin lived, was the capital of the piano world. The middle class was expanding, and there was a growing market for pianos, tuition, and sheet music, as well as for concerts featuring virtuoso pianists like Chopin. There was also demand for études (studies): compositions for piano, written as exercises in different pianistic techniques. Composers like Clementi and Czerny wrote dozens of études and exercises and the sheet music sold in great numbers to student and amateur pianists.

Chopin earned his money through teaching and composing. Naturally enough, he turned his hand to the étude. But he decided not to do it in the usual way. Instead of putting together a series of elegant but dry technical exercises - eminently marketable - he poured his creative soul into the project. He composed a series of miniature tone poems, full of poetry, drama, and delight. Today, Chopin’s Études are one of the cornerstones of the concert piano repertoire. They do work as pedagogical tools; each one is focused on a particular technical challenge - arpeggios, trills, left-hand runs - but they are also expressive, emotional works of art. (For a recent recording, try Yunchan Lim).

Chopin took a modest form and made something extraordinary out of it. I don’t know what exactly motivated him to do this - perhaps sheer boredom at the prospect of turning out mere studies; I suspect he did it for himself as much as for anyone else. Bu it turned out to be a good strategic move, showcasing his originality as a composer and helping him to reach a wider audience.

In any field, AIs will soon be able to do the technical exercises as well or better than any of us. Where you can impose your personality on your work and make it your own, as if you’re an artist finding her voice rather than just a technician carrying out tasks, you should.Be difficult to model. If your job can be reduced to a series of operations, of procedures and rules, then even if you’re very competent at executing those operations, you may find yourself at risk from machines who don’t do it as quite well as you but are a lot cheaper and don’t take holidays. If you do your job in a valuable way that is also a very hard way to encode then you will be safer. To take an example from close to my field, there are journalists and copywriters who are skilled, efficient deliverers of information who will find it harder to get work. The writers who have unmistakable individual voices, and who are also at least somewhat unpredictable in what they say or how they write, are in a better position.

This is a habit of mind and behaviour as much as it is a professional strategy. We should all be trying to evade the algorithmic reaper. In information theory, “entropy” measures unpredictability or surprise. The higher the entropy of a message, the more new information it contains. Julia Galef refers to ‘high-entropy thinkers’. When you ask a high-entropy thinker for their views on some political or social issue it’s hard to predict what they’re going to say because they approach every question afresh through the lens of a very individual sensibility. Most us aren’t like that. We offer up predictable opinions which come bundled up in pre-wrapped packages. Martin Amis’s “war against cliché” is a war on linguistic predictability.2 Apply to every area of work.

Being unpredictable isn’t enough, of course; you have to try and be unpredictable and right, or at least interesting, as often as possible. That means combining a suspicion of the conventional (easy) with actual knowledge and thought (hard). Paul Graham has a good essay about being independent-minded. One question it’s worth asking yourself is how and whether your views about the world differ in significant ways from your closest friends and peers. If they don’t, perhaps you’re not fully in the habit of thinking for yourself; if so, your thinking is likely to be easy to model in general.